Scientists have developed the first comprehensive catalog of the genetic aberrations responsible for an aggressive type of ovarian cancer that accounts for 70 percent of all ovarian cancer deaths.

Hundreds of researchers from more than 80 institutions, including scientists from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), deciphered the genome structure and gene expression patterns in high-grade serous ovarian adenocarcinomas from almost 500 patients. They also sequenced the protein-coding part of the genome in about 320 of these patients. The result is the most expansive genomic analysis of any cancer to date and a major step toward the personalized treatment of ovarian cancer. The research is described in the June 30 issue of the journal Nature.

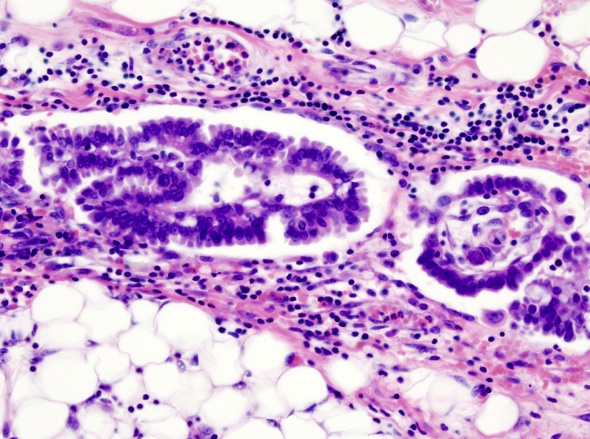

Ovarian cancer accounts for about three percent of all cancers in women. This histopathological image shows serous adenocarcinoma in bilateral ovaries. (source: Wikimedia)

Their work could lead to a day in which doctors treat high-grade serous ovarian cancer by detecting the aberrant genes in a patient, and targeting these genes with therapies that are most effective against the specific mutations. It could also guide the development of new pharmaceuticals that are specially tailored to fight mutations that cause ovarian cancer.

The project was conducted under the auspices of the The Cancer Genome Atlas, an effort led by the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute and National Human Genome Research Institute to improve cancer care by understanding the genetic causes of the disease.

Paul Spellman of Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division is the corresponding author of the Nature article. Several other Berkeley Lab scientists contributed to the research, including renowned cancer researcher Joe Gray, a guest senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division. The project required collaboration among experts across the nation in tissue analysis, genome sequencing, cancer genomics, and data analysis.

“The Cancer Genome Atlas is about giving a parts list to the cancer community. Clinicians can use the data to propel the next wave of discoveries, such as new cancer therapies and early-detection methods,” says Spellman. “We are the first to systematically catalog the genetic mutations associated with ovarian cancer.”

Ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer death among women in the U.S., with almost 22,000 new cases and 14,000 deaths estimated for 2010 according to the National Cancer Institute. High-grade serous ovarian cancer, which begins in the cells on the surface of the ovary, accounts for 90 percent of all ovarian cancers and often remains undetected until it’s quite advanced.

The standard of care is aggressive surgery followed by platinum-taxane chemotherapy. After therapy, however, platinum-resistant cancer recurs in approximately 25 percent of patients within six months and the overall 5-year survival rate is 31 percent. Because of this, scientists are seeking potent and targeted ways to fight the disease, which requires a thorough understanding of its genetic roots.

To do this, The Cancer Genome Atlas program brought together scientists from a wide range of disciplines and research institutions. More than two dozen sites provided tissue samples of ovarian tumors. Scientists at other sites performed gene expression analysis, DNA sequencing, and other analyses. The resulting data was fed to two repositories and analyzed by members of the network including Berkeley Lab scientists.

Among their many findings, the team determined that the causes of ovarian cancer are not confined to changes affecting individual genes. Large structural changes in a cancer’s genome — in which genes are erroneously deleted or duplicated — are also important. Scientists knew that ovarian cancer genomes have gene copy errors, but they didn’t know these hiccups are such a big driver of the disease.

They also found a possible new front in the fight against ovarian cancer. They tallied a group of about 30 gene mutations that plays a role in the disease, but which individually occur in only 1 to 2 percent of patients. A small number of patients had mutations of the BRAF gene. Another small subset had mutations of the Rb2 gene, which is common in breast cancer but not in ovarian cancer. And yet another subset had a mutation in a gene that codes for the production of the PI 3-kinase enzyme.

These mutations are quite rare by themselves, but together they’re found in almost 20 percent of ovarian cancer patients. Therapies already exist for many of these mutations, such as an inhibitor that silences the BRAF mutation, and others are in development.

“These are actionable rare events,” says Spellman. “They are very specific mutations that, if detected, clinicians can possibly go after — which opens up a whole new way to fight the disease.”

They also determined that a network of genes that repairs damaged DNA is defective in about half the tumors. Patients with this defect may benefit from therapies that inhibit this errant function. And they found that the spectrum of mutations in high-grade serous ovarian cancer is distinct from three other ovarian cancer subtypes, which are themselves distinct from each other.

“This represents an opportunity to improve cancer care by approaching the treatment of each subtype differently,” says Spellman.

Other findings include the fact that almost all patients with high-grade serous ovarian cancers have a mutation in the TP53 gene, which codes for a tumor-suppressing protein. This buttresses earlier research that underscored the importance of the TP53 gene mutation in ovarian cancer. In addition, almost a quarter of patients had BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations, which also reaffirms earlier research.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health. In addition to the ovarian cancer study, The Cancer Genome Atlas is conducting large-scale genomic analyses of 19 other types of cancer, which are chosen in part because of their public health impact and poor prognosis.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 12 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

Additional information:

- The research is described in a paper entitled “Integrated Genomic Analyses of Ovarian Carcinoma” that is published in the June 30, 2011 issue of Nature. The paper lists the scientists and institutions involved in the research.

- More about The Cancer Genome Atlas

- Paul Spellman is a staff scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division. Beginning July 1, he will be a guest scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division and an associate professor in the Department of Molecular and Medical Genetics at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU).

- Joe Gray is a guest senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Life Sciences Division. He is also the Gordon Moore Professor and Chair, OHSU’s Department of Biomedical Engineering; Director, OHSU Center for Spatial Systems Biomedicine; Associate Director for Translational Research, OHSU Knight Cancer Institute; Emeritus Professor, University of California San Francisco.