In perhaps no other scientific field does the adage “form follows function” hold more true than in biology, especially the biology of living cells, which is why our knowledge of cells starts with imaging. Optical microscopy is limited by low spatial resolution – about 200 nanometers, and electron microscopy is limited by the poor penetration of electrons and the requirement that it be performed in a vacuum, which means cells must be sectioned off into tissue-thin slices and dehydrated. X-ray microscopy bridges the resolution gap between optic and electron microscopy, combining the best features of both to hit the sweet spot for chemical and elemental imaging.

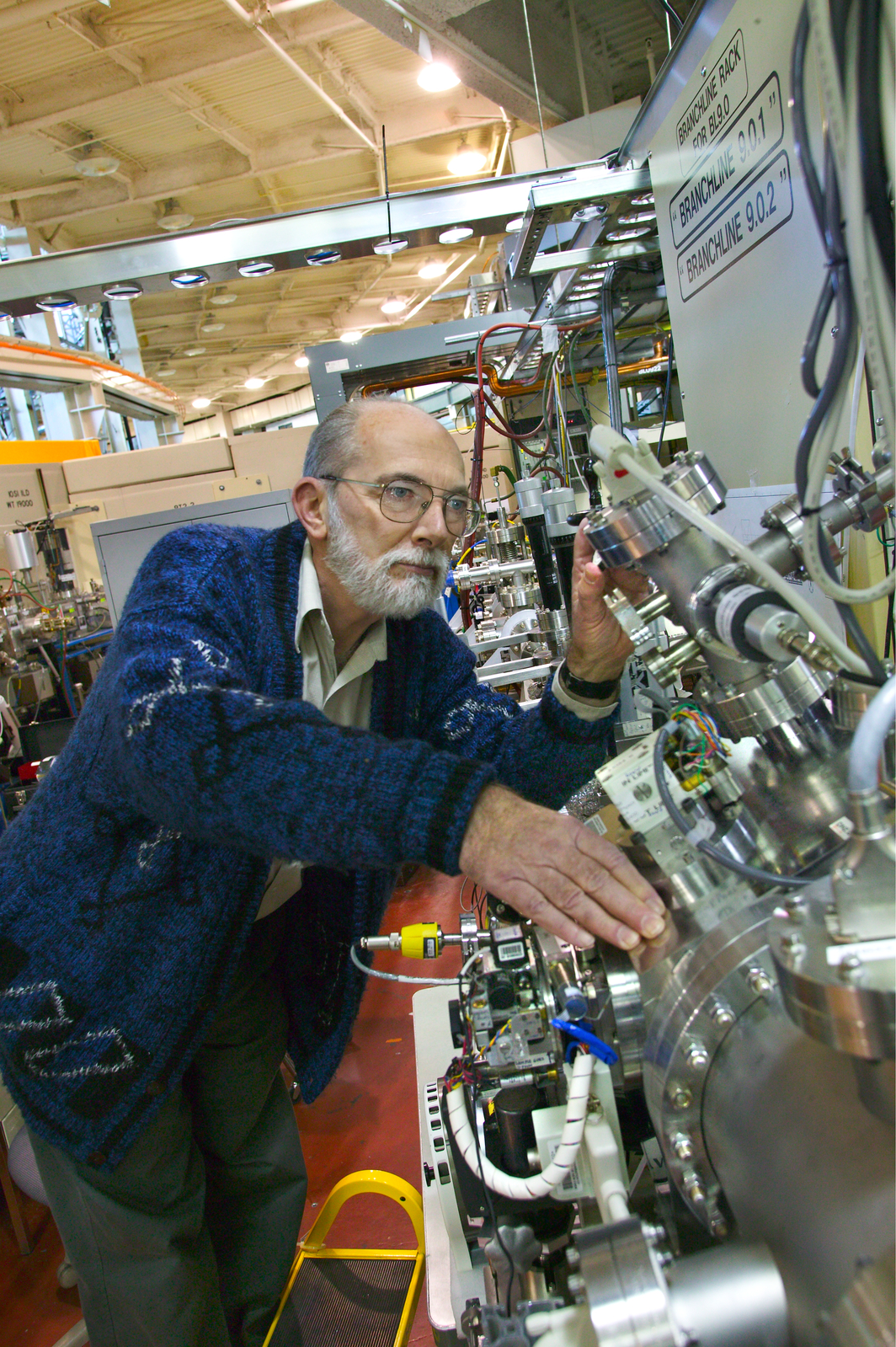

“Advances in X-ray sources, detectors, instrumentation and computing power are transforming X-ray microscopy from a scientific curiosity practiced by a few specialists, to a widely available form of high resolution imaging,” says Janos Kirz, scientific advisor for Lawrence Berkeley National Lab’s Advanced Light Source, a synchrotron radiation source optimized for soft x-ray and ultraviolet light.

“State-of-the-art X-ray microscopes can be used to create three-dimensional images with elemental and/or chemical sensitivity,” Kirz says. “Some instruments are also capable of creating movies, or providing stop-motion or flash images of cells and proteins in their natural hydrated state.”