A new approach to sending acoustic waves through water could potentially open up the world of high-speed communications to activities underwater, including scuba diving, remote ocean monitoring, and deep-sea exploration.

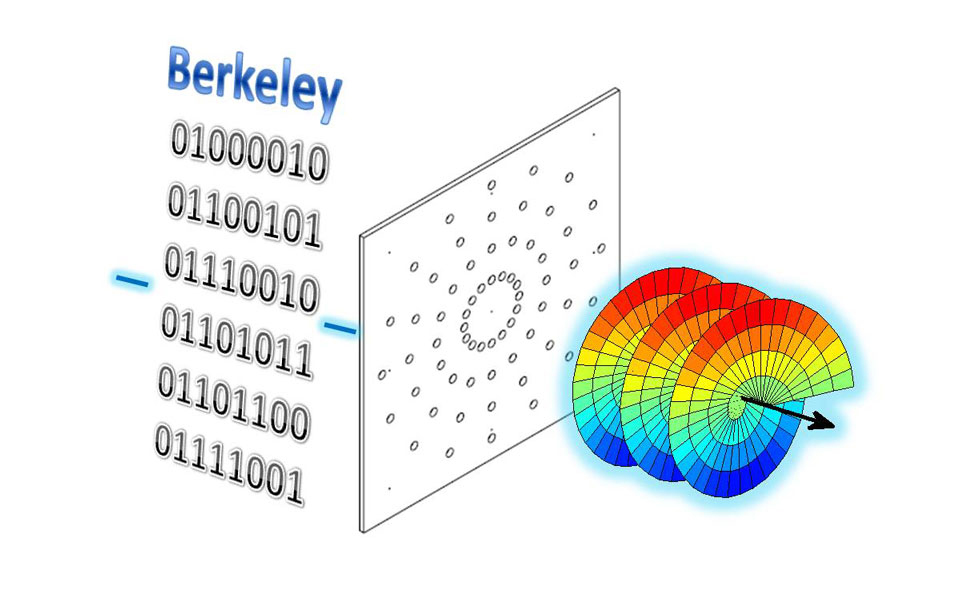

Binary data representing the word “Berkeley” is converted by a digital circuit to information encoded in independent channels with different orbital angular momentum. The transducer array sends the information via a single acoustic beam with different patterns. The colors in the helical wavefront show different acoustic phases. (Credit: Chengzhi Shi/Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley)

By taking advantage of the dynamic rotation generated as acoustic waves travel, or the orbital angular momentum, researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) were able to pack more channels onto a single frequency, effectively increasing the amount of information capable of being transmitted.

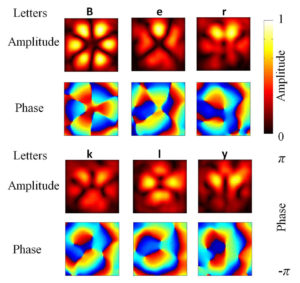

They demonstrated this by encoding in binary form the letters that make up the word “Berkeley,” and transmitting the information along an acoustic signal that would normally carry less data. They describe their findings in a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“It’s comparable to going from a single-lane side road to a multi-lane highway,” said study corresponding author Xiang Zhang, senior faculty scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and a professor at UC Berkeley. “This work has huge potential in high-speed acoustic communications.”

While human activity below the surface of the sea increases, the ability to communicate underwater has not kept pace, limited in large part by physics. Microwaves are quickly absorbed in water, so transmissions cannot get far. Optical communication is no better since light gets scattered by underwater microparticles when traveling over long distances.

Low frequency acoustics is the option that remains for long-range underwater communication. Applications for sonar abound, including navigation, seafloor mapping, fishing, offshore oil surveying, and vessel detection.

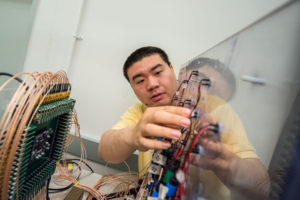

Chengzhi Shi checks the connections between the transducer array and the digital circuit. The experimental setup showed the potential of generating independent channels onto a single frequency to expand acoustic communications underwater. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

However, the tradeoff with acoustic communication, particularly with distances of 200 meters or more, is that the available bandwidth is limited to a frequency range within 20 kilohertz. Frequency that low limits the rate of data transmission to tens of kilobits per second, a speed that harkens back to the days of dialup internet connections and 56-kilobit-per-second modems, the researchers said.

“The way we communicate underwater is still quite primitive,” said Zhang. “There’s a huge appetite for a better solution to this.”

The researchers adopted the idea of multiplexing, or combining different channels together over a shared signal. It is a technique widely used in telecommunications and computer networks, but multiplexing orbital angular momentum is an approach that had not been applied to acoustics until this study, the researchers said.

As sound propagates, the acoustic wavefront forms a helical pattern, or vortex beam. The orbital angular momentum of this wave provides a spatial degree of freedom and independent channels upon which the researchers could encode data.

“The rotation occurs at different speeds for channels with different orbital angular momenta, even while the frequency of the wave itself stays the same, making these channels independent of each other,” said study co-lead author Chengzhi Shi, a graduate student in Zhang’s lab. “That is why we could encode different bits of data in the same acoustic beam or pulse. We then used algorithms to decode the information from the different channels because they’re independent of each other.”

Letters are encoded onto independent channels, with the amplitudes and phases forming different patterns. (Credit: Chengzhi Shi/Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley)

The experimental setup, located at Berkeley Lab, consisted of a digital control circuit with an array of 64 transducers, together generating helical wavefronts to form different channels. The signals were sent out simultaneously via independent channels of the orbital angular momentum. They used a frequency of 16 kilohertz, which is within the range currently used in sonar. A receiver array with 32 sensors measured the acoustic waves, and algorithms were used to decode the different patterns.

“We modulated the amplitude and phase of each transducer to form different patterns and to generate different channels on the orbital angular momentum,” said Shi. “For our experiment we used eight channels, so instead of sending just 1 bit of data, we can send 8 bits simultaneously. In theory, however, the number of channels provided by orbital angular momentum can be much larger.”

The researchers noted that while the experiment was done in air, the physics of the acoustic waves is very similar for water and air at this frequency range.

Expanding the capacity of underwater communications could open up new avenues for exploration, the researchers said. This added capacity could eventually make the difference between sending a text-only message and transmitting a high-definition feature film from below the ocean’s surface. Remote probes in the oceans could send data without the need to surface.

“We know much more about space and our universe than we do about our oceans,” said Shi. “The reason we know so little is because we don’t have the probes to easily study the deep sea. This work could dramatically speed up our research and exploration of the oceans.”

The other researchers on this team are co-lead author Marc Dubois and co-author Yuan Wang, both members of Zhang’s group.

This research is supported by the UC Berkeley Ernest Kuh Chair Endowment, a UC Berkeley Graduate Student Fellowship, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.