Berkeley Lab and UC Berkeley scientists were part of a team that helped to decipher one of the most bizarre spectacles ever seen in the night sky: A supernova that refused to stop shining, remaining bright far longer than an ordinary stellar explosion. What caused the event is puzzling.

A Las Cumbres Observatory press release about the supernova, which was discovered by the Palomar Transient Factory in September 2014, noted that the explosion at first appeared to be an ordinary supernova. “Several months later … astronomers noticed something that they had never seen before – the supernova was growing brighter again after it faded,” the release stated, and “may have been the most massive stellar explosion ever seen.”

The discovery is detailed in a study published today in the journal Nature.

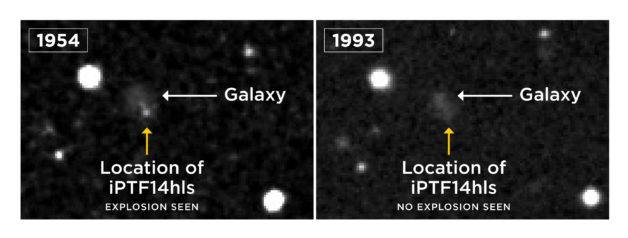

The release also notes that the supernova “grew brighter and dimmer at least five times over two years,” while typically supernovae fade over the first several months. Also, scientists found evidence that there was another explosion in the same location in 1954.

This star’s size could have a lot to do with its mysterious behavior, scientists said.

“It is possible that this was the result of star so massive and hot that it generated antimatter in its core,” said Daniel Kasen, a scientist in the Berkeley Lab Nuclear Science Division and associate professor in the Physics and Astronomy departments at UC Berkeley who participated in the study. “That would cause the star to go violently unstable, and undergo repeated bright eruptions over periods of years.”

Kasen had assisted in attempts to model the physics behind the star’s odd behavior, but there are a lot of unknowns about what’s at work.

Peter Nugent, a senior staff scientist in the Computational Research Division at Berkeley Lab and an adjunct professor of astronomy at UC Berkeley who also took part in the study, had helped to lead observations of the exotic star explosion at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii.

Computer resources at Berkeley Lab’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC) were used to locate the September 2014 star explosion.

“The spectra (light signature) we obtained at Keck showed that this supernova looked like nothing we had ever seen before,” Nugent said, “and this is after discovering nearly 5,000 supernovae in the last two decades.

“While the spectra bear a resemblance to normal hydrogen-rich core-collapse supernova explosions, they evolved six times more slowly, stretching an event which normally lasts 100 days to over two years.”

An image taken by the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey reveals a possible explosion in the year 1954 at the location of iPTF14hls (left), not seen in a later image taken in 1993 (right). Supernovae are known to explode only once, shine for a few months and then fade, but iPTF14hls experienced at least two explosions, 60 years apart. Adapted from Arcavi et al. 2017, Nature. (Credit: POSS/DSS/LCO/S. Wilkinson)

Nugent also said that the observations suggested single or multiple detached shells of material ejected prior to the recent supernova explosion, “which has been predicted for stars that are 100 times the mass of our sun.”

Compiling observations from Keck, the Palomar Transient Factory, Las Cumbres Observatory, and even 1954 images from the Palomar Sky Survey has offered some clues about the object.

But, he noted, “This is one of those head-scratcher type of events. At first we thought it was completely normal and boring as it started to fade a little. And then it got brighter, faded and got brighter, repeating this several more times month after month.”

NERSC is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.