Just as people can be left-handed or right-handed, scientists have observed chirality or “handedness” in swirling electric vortices in a layered material. (Credit: Pixabay)

Scientists used spiraling X-rays at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) to observe, for the first time, a property that gives handedness to swirling electric patterns – dubbed polar vortices – in a synthetically layered material.

This property, also known as chirality, potentially opens up a new way to store data by controlling the left- or right-handedness in the material’s array in much the same way magnetic materials are manipulated to store data as ones or zeros in a computer’s memory.

Researchers said the behavior also could be explored for coupling to magnetic or optical (light-based) devices, which could allow better control via electrical switching.

Chirality is present in many forms and at many scales, from the spiral-staircase design of our own DNA to the spin and drift of spiral galaxies; it can even determine whether a molecule acts as a medicine or a poison in our bodies.

A molecular compound known as d-glucose, for example, which is an essential ingredient for human life as a form of sugar, exhibits right-handedness. Its left-handed counterpart, l-glucose, though, is not useful in human biology.

“Chirality hadn’t been seen before in this electric structure,” said Elke Arenholz, a senior staff scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS), which is home to the X-rays that were key to the study. The study was published online this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The experiments can distinguish between left-handed chirality and right-handed chirality in the samples’ vortices. “This offers new opportunities for fundamentally new science, with the potential to open up applications,” she said.

“Imagine that one could convert a right-handed form of a molecule to its left-handed form by applying an electric field, or artificially engineer a material with a particular chirality,” said Ramamoorthy Ramesh, a senior faculty scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Sciences Division and associate laboratory director of the Lab’s Energy Technologies Area, who co-led the latest study.

Ramesh, who is also a professor of materials science and physics at UC Berkeley, custom-made the novel materials at UC Berkeley.

Padraic Shafer, a research scientist at the ALS and the lead author of the study, worked with Arenholz to carry out the X-ray experiments that revealed the chirality of the material.

The samples included a layer of lead titanate (PbTiO3) and a layer of strontium titanate (SrTiO3) sandwiched together in an alternating pattern to form a material known as a superlattice. The materials have also been studied for their tunable electrical properties that make them candidates for components in precise sensors and for other uses.

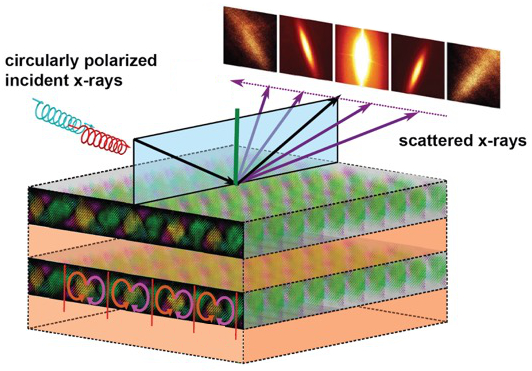

This diagram shows the setup for the X-ray experiment that explored chirality, or handedness, in a layered material. The blue and red spirals at upper left show the X-ray light that was used to probe the material. The X-rays scattered off of the layers of the material (arrows at upper right and associated X-ray images at top), allowing researchers to measure chirality in swirling electrical vortices within the material. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

Neither of the two compounds show any handedness by themselves, but when they were combined into the precisely layered superlattice, they developed the swirling vortex structures that exhibited chirality.

“Chirality may have additional functionality,” Shafer said, when compared to devices that use magnetic fields to rearrange the magnetic structure of the material.

The electronic patterns in the material that were studied at the ALS were first revealed using a powerful electron microscope at Berkeley Lab’s National Center for Electron Microscopy, a part of the Lab’s Molecular Foundry, though it took a specialized X-ray technique to identify their chirality.

“The X-ray measurements had to be performed in extreme geometries that can’t be done by most experimental equipment,” Shafer said, using a technique known as resonant soft X-ray diffraction that probes periodic nanometer-scale details in their electronic structure and properties.

Spiraling forms of X-rays, known as circularly polarized X-rays, allowed researchers to measure both left-handed and right-handed chirality in the samples.

Arenholz, who is also a faculty member of the UC Berkeley Department of Materials Science & Engineering, added, “It took a lot of time to understand the results, and a lot of modeling and discussions.” Theorists at the University of Cantabria in Spain and their network of computational experts performed calculations of the vortex structures that aided in the interpretation of the X-ray data.

The same science team is pursuing studies of other types and combinations of materials to test the effects on chirality and other properties.

“There is a wide class of materials that could be substituted,” Shafer said, “and there is the hope that the layers could be replaced with even higher functionality materials.”

Researchers also plan to test whether there are new ways to control the chirality in these layered materials, such as by combining materials that have electrically switchable properties with those that exhibit magnetically switchable properties.

“Since we know so much about magnetic structures,” Arenholz said, “we could think of using this well-known connection with magnetism to implement this newly discovered property into devices.”

The Advanced Light Source and the Molecular Foundry are both DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

Also participating in the research were scientists from the UC Berkeley Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, the Institute of Materials Science of Barcelona, the University of the Basque Country, and the Luxembourg Institute of Science and Technology. The work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, the National Science Foundation, the Luxembourg National Research Fund, the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness, and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.