Two poets walk into an 88-Inch Cyclotron … and what happens next is an uncommon pairing of accelerated particles and artistic expression.

The visiting poets – Kate Greene, a former Berkeley Lab science writer who is an author, essayist, journalist, and poet; and fellow poet, writer, and science enthusiast Anastasios Karnazes – drew inspiration from an overnight stay at the cyclotron from June 14-15 at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

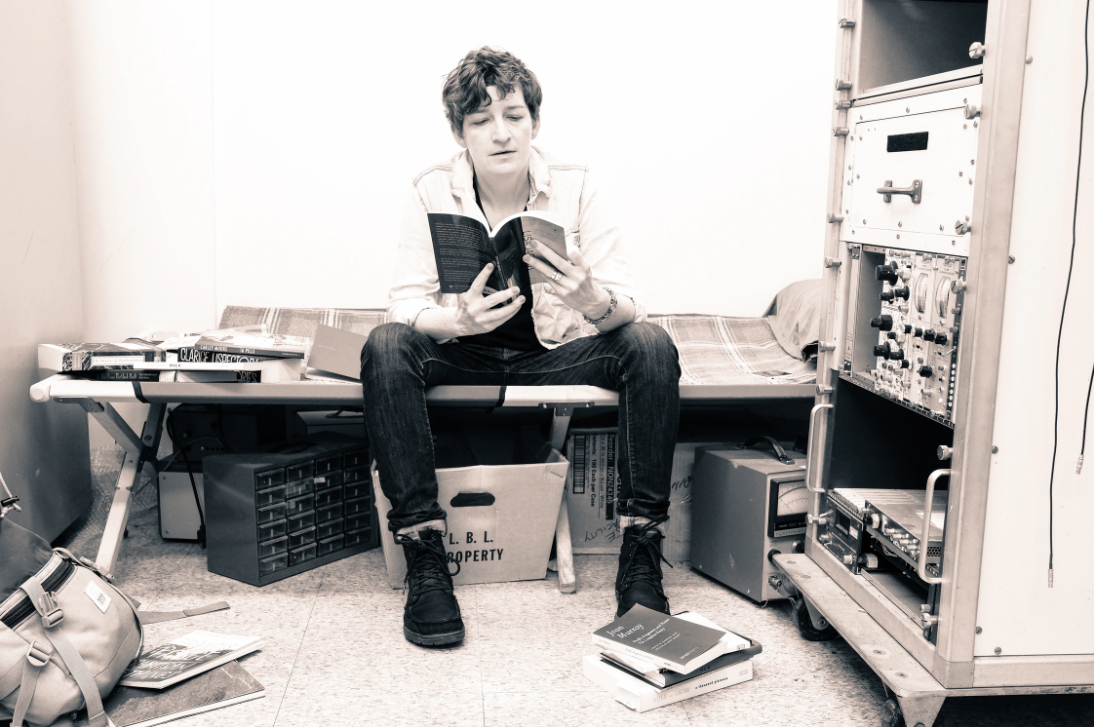

Greene and Karnazes met while pursuing master’s degrees in a writing program at Columbia University in New York City. They brought poetry and philosophy works to keep them company during their night at the Lab’s 55-year-old cyclotron. Through the night they wrote, shared readings with one another, and spoke with cyclotron workers.

Poets are like cyclotrons in their ability to both “break and remake,” they noted in a summary statement explaining the purpose of their visit: Cyclotrons can create new elements by fusing atomic nuclei together in high-energy particle beam experiments that bombard one type of element with another, for example, and poets “have been deconstructing and reconfiguring ideas, emotions, experiences, and truths” via a range of devices.

Poets can also play around with time in interesting ways. Greene and Karnazes cited a quote by Bay Area poet Jack Spicer: “A poet is a time mechanic not an embalmer.” Particle accelerator experiments similarly can dissect and explore time at many different scales.

“Poetry is good for reminding people about time and about different speeds of time,” Karnazes said. “Poetry reminds me to stay present and question the speed at which I am experiencing the world.”

Greene noted that scientists and poets can both convey incredibly dense, layered concepts with choice few letters: Think of Einstein’s “E =mc2” theory that describes the mass and energy equivalence in the universe, or Shakespeare’s “To be, or not to be.” She said, “The poem is able to take something as huge as love or death or grief or ambition … and compress them into a few lines.”

She added, “I think a lot of scientists are secret poets. The modes of exploration are quite similar, and the physical embodiment of discovery feels the same, too.”

As a child, Greene aspired to be an astrophysicist. “Space was my avenue to science,” she said. Her early sci-fi faves included the Steven Spielberg-directed film “E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial” and the television series “Star Trek: The Next Generation.”

She pivoted toward chemistry as an undergraduate student, dabbling in laser and semiconductor science, and got a master’s degree in physics at the University of Kansas. Astrochemistry, which is now an established field, was regrettably not a pronounced career path at the time, she noted. It would have suited her interests perfectly. A strong writer, she dove into professional writing and kept her sights on science. In 2013 she landed an opportunity to participate in a months-long NASA project that simulated a Mars-mission habitat on a Hawaiian volcano.

That experience, which she is now detailing in a book, shaped and refocused her writing, she said. “I came back to San Francisco and started writing poems in a way I hadn’t before. I was reading all the books I could.” She met with Cecil Giscombe, a UC Berkeley English professor, to discuss poetry, and that led her to pursue the master’s degree writing program at Columbia University.

“When I was preparing experiments for the simulated Mars mission, I felt the excitement of discovery in a way that I hadn’t when I was doing my graduate work in physics,” she said. “Later, when I was writing poems, I had that same physical excitement of discovery. That surprise and delight of discovery is something that poets and scientists share.”

For Karnazes, science was a common ground that he shared with his uncle, who lives in Greece. “I’m not very fluent in Greek, and he’s not very fluent in English,” Karnazes said.

“I read a bunch of string theory books in middle school and high school. It was an interesting thing to me back then,” he said. “It was one of the first things I felt like I understood completely, particularly because it was a way to communicate with my uncle.”

He added, “The love we shared through that made me care about particle physics and string theory, and all of those sorts of things, at a young age.” And over time he also found a particular interest in language and how it evolves, and a resonance in poetry, which provided an accessible platform to communicate and connect deeply with others – and it didn’t require the same academic labeling as a “philosopher.”

“Poetry is a way to write your grand expression of metaphysics right now. You don’t have to be researching something for 70 years before you get to play with it,” Karnazes said. “You can access your heart and compassion immediately in poetry, and that’s very nice.”

The visit to the cyclotron, Greene said, wasn’t her first, but it had a surreal feel because of the off-hours, “the shifting cast of characters throughout the night,” and all of the busy work taking place around them while they bore witness and composed poems.

Greene and Karnazes said they would also like to visit other science facilities, including CERN laboratory in Switzerland, where the Higgs boson was discovered.

More: