Lynn Yarris, (510) 486-5375, [email protected]

Humans have been star-gazing for thousands of years but the surprises keep coming. Recently, members of the Supernova Cosmology Project, one of the two groups that ten years ago told the world about the existence of “dark energy,” announced the observation of a mysterious object that grew increasingly bright for about 100 days then faded away to nothing over the next 100 days. Astronomers have never reported anything like it before and still don’t know what it was.

“It is exciting to know that there are still at least a few things out there that we haven’t found yet,” says Saul Perlmutter, an astrophysicist with the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) who heads the international scientific collaboration known as the Supernova Cosmology Project. “I don’t think we will really know what this discovery means until we can explain it or observe similar objects in the future.”

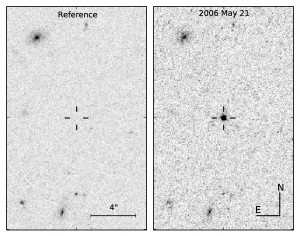

In the optical equivalent of something going bump in the night, a mysterious object in an apparently empty patch of space (see hash marks) brightened by a factor of at least 120 times during a period of about three months and then faded away over the next three months. (Image courtesy of Kyle Barbary)

Using the Hubble Space Telescope to survey clusters of distant galaxies for supernovae (exploding stars), Perlmutter and his team observed what they described as an “unusual optical transient.” Although the transient object appeared in the direction of a cluster of galaxies more than 8 billion light years away in the constellation known as Bootes, it was not located in any detectable galaxy or progenitor star. Nor did this object behave like any known supernova type, nor could it be matched to any spectrum in the Sloan Digital Sky Survey database, which has recorded millions of galaxies and quasars.

This discovery will be reported in the Astrophysical Journal in a paper entitled: “Discovery of an Unusual Optical Transient with the Hubble Space Telescope.” The lead author on this paper is Kyle Barbary, a member of the Supernova Cosmology Project and Perlmutter’s research group.

“Typically, the spectrum of a transient optical object can tell it’s whole story: what it is, what it is made of, how far away it is,” says Barbary. “We do this by identifying features in the spectrum and attributing them to various elements. However, while this transient has striking features, so far we haven’t been able to positively identify them.”

Researchers with the Supernova Cosmology Project detect and measure the brightness of type Ia supernovae. Since the intrinsic brightness of every type Ia supernova is the same, these exploding stars can serve as “standard candles” for measuring distances – the dimmer the light, the further away from Earth the supernova is. Once measured, the distance of a type Ia supernova can be compared to the redshifts of its home galaxy to reveal how fast that portion of the universe is receding from Earth.

This technique enabled Perlmutter and his Supernova Cosmology Project colleagues to discover in 1998 that a mysterious anti-gravitational force – dubbed Dark Energy – is causing the universe to expand at an accelerating rate.

Kyle Barbary (left) and Saul Perlmutter, researchers at Berkeley Lab, the base institute for the Supernova Cosmology Project, were the lead authors of a paper that announced the discovery of an “unusual optical transient”

“The discovery of this optical transient was really a side project for the Supernova Cosmology Project,” says Barbary. “It wasn’t the goal of our survey to look for new things, but when we found this object it was so intriguing that we wanted to put the data out there and see what people could come up with to explain it.”

Scientists have already put forth several possible explanations including the explosion of an ancient star whose atmosphere was heavy with molecular carbon, and gravitational microlensing, the phenomenon by which light from a dim object is magnified by a massive gravitational field. Barbary, however, is for the moment skeptical.

“The explanations advanced so far are not that convincing,” he says. “I think it is also possible that this optical transient originates from the outskirts of our own galaxy, possibly a white dwarf or a neutron star. The good news is that we got a relatively large amount of data. We were able to get not only the full lightcurve, but a spectrum at three different dates using three different telescopes. Once we are able to more fully identify the spectral features of this object, we will probably be able to figure out what it is.”

Identifying what the optical transient object is will probably not come any time soon, however, as sifting through and analyzing the data for cosmological discoveries can be a painstaking process. This mystery object was first observed on February 21, 2006. It took numerous observations to confirm that the object was “a very unusual transient.” Data continued to be taken (the last data-point was obtained in May 2007), before a full analysis got underway.

“It took us quite some time to study the data and carefully consider the possibilities of what this optical transient might be,” says Barbary.

Pending further analysis and perhaps the discovery of similar objects elsewhere in the universe, the identify of this optical transient for now will remain a mystery.

This research was supported by the Office of Science in the U.S. Department of Energy, through the Office of High Energy and Nuclear Physics, and by NASA.

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California. Visit our Website at www.lbl.gov/

Additional information

For more information contact Kyle Barbary at [email protected]

or Saul Perlmutter at [email protected]

A pdf version of paper is available for viewing now at http://arxiv.org/PS_cache/arxiv/pdf/0809/0809.1648v1.pdf