Imagine if Californians awoke one morning to learn that the Governor’s Office was planning to build a huge wind park off the state’s northern coast, consisting of 2500 giant wind turbines.

Imagine, too, that there was a hydro energy storage component to the project that required that two small valleys near the coast be flooded with sea water.

Imagine then that hundreds of thousands of Californians reacted over the next hours and days—not with outrage but with endorsements, signing on to a website to donate their time and services to help make it happen.

No, this is not a fantasy. This is Ireland, or more correctly the Spirit of Ireland, a wind-energy-to-hydro-energy project proposed for the comparatively unpopulated western coast of Europe’s westernmost country.

The project’s website, discussed at a Euroscience Open Forum session entitled Taming the Wind: a Strategic Energy Option for Europe, reads like a battle cry. ( Not surprisingly, the Spirit of Ireland is subtitled “a national project for energy independence”):

We have the energy, imagination and skills to solve our problems and create a bright future for our children and future generations. A breakthrough National Project will create:

- Tens of thousands of jobs

- Achieve energy independence in five years

- Save €30 billion importing fossil fuels

- Create potential to add €50bn to our Economy

- Slash carbon dioxide emissions

We are all obliged to use our wonderful natural gifts, resources and talents to create a new future for our nation.

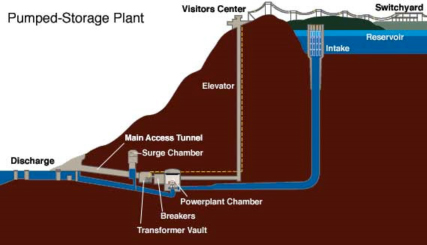

Why flood the picturesque valleys, you ask? Typically, wind farms only produce 25 to 35 percent of their maximum possible electricity output, depending on their location. If the electricity they do generate is transmitted to a pump in a low lying reservoir, it can be used to pump water uphill to a higher reservoir in the flooded valley. When electrical demand is high, the process can be reversed. As the water flows through a turbine on its way back downhill, it generates electricity. This offsets the variability of the wind farms and turns the pumped hydro storage facility into a big load-balancing machine.

Round-trip energy efficiency is projected to be 80 to 84 percent, a figure considered to be state-of-the-art, and with the help of two 2.5 mile by 2.5 mile reservoirs, good enough to provide Ireland with its national electricity requirements. Better yet, say proponents, constructing a further three plants would earn very large incomes from export of natural energy. “We want to become the rechargeable battery for Europe,” said Igor Shvets of Trinity College’s School of Physics.

This is not an idle boast. It’s estimated that Ireland, which knows well the force of prevailing winds blowing across the Atlantic, has 6 percent of the EU’s total wind resources. (The Danes also have large wind resources and presented their impressive history and deployment of wind power since the oil shock of the 1970s.)

Of course, what Ireland and Denmark have in common is their small size and short distance from energy source to large population centers.

When asked by a skeptical American in the audience about how such a wind system would work in North America, the presenters made a spirited claim that vast amounts of wind power could be generated up the Mississippi River Valley and delivered to both coasts. Details were vague and as the panelists went on to answer the next question, the skeptical American grumbled to no one in particular, “That means that it won’t work.”

Don’t tell that to the Irish.