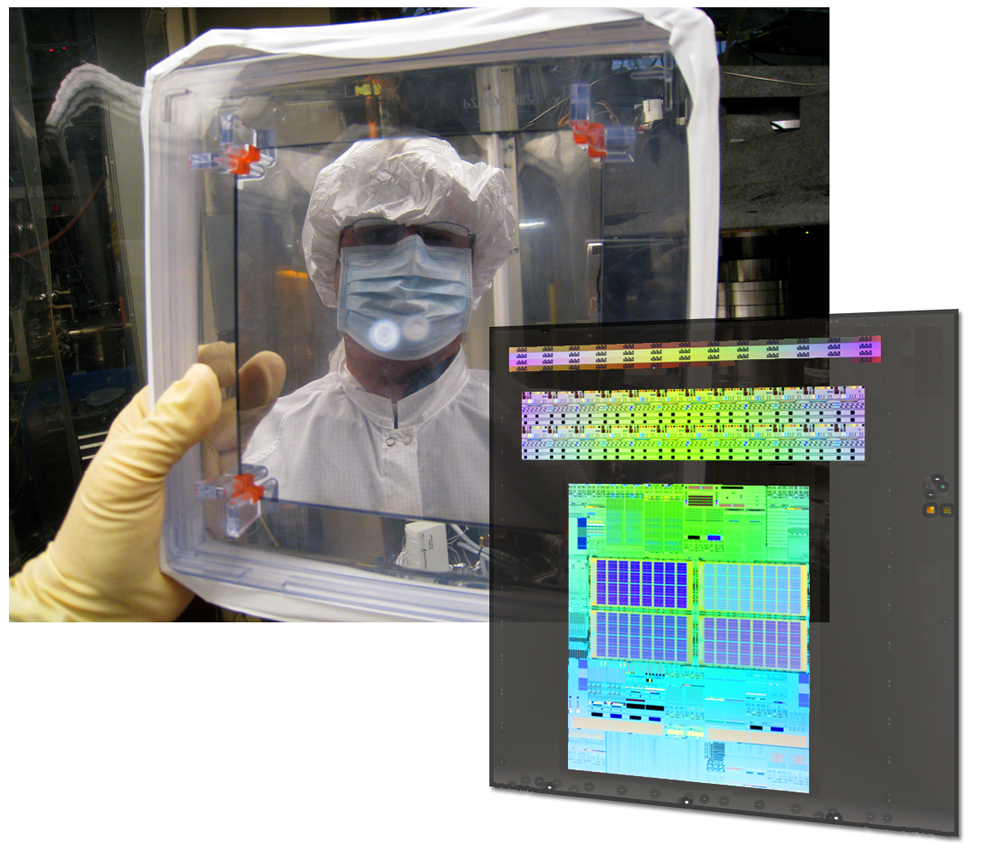

Kenneth Goldberg is seen in the reflective coating of a photolithography mask, contained in the clear plastic box, which he’s about to measure at the Advanced Light Source’s beamline 11.3.2. Inset at lower right shows a mask’s extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) absorbing layer, printed on a six-inch square of glass coated with multiple layers of molybdenum and silicon only billionths of a meter thick to reflect unwanted EUV. The patterned layer represents one level of a working microprocessor or memory chip, which may have 20 or more such levels. Its structures are less than one ten-millionth of a meter across and diffract visible light in rainbow patterns.

Moore’s Law, hardly a law but undeniably a persistent trend, says that every year and a half, the number of transistors that fit on a chip roughly doubles. It’s why electronics – from smart phones to flat screens, from MP4 players to movie cameras, from tablets to supercomputers – grow ever more varied, powerful, and compact, but also ever less expensive. Whether the trend can continue until it runs up against immutable laws of nature, like the finite size of an atom, depends on how far scientists and technicians can push electronic technologies down into the nanoworld with better tools for using short-wavelength light.

Now scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have partnered with colleagues at leading semiconductor manufacturers to create the world’s most advanced extreme-ultraviolet (EUV) microscope. Called SHARP (a succinct acronym for a long name, the Semiconductor High-NA Actinic Reticle Review Project), the new microscope will be dedicated to photolithography, the central process in the creation of computer chips.

The $4.1 million, 1.5-year project will be led by Kenneth Goldberg of the Center for X-Ray Optics (CXRO) in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Science Division (MSD). Initially SHARP will be used in parallel with operations at the existing microscope on beamline 11.3.2 of Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source (ALS). By the last quarter of 2012 the new EUV photomask-imaging microscope will replace the beamline’s aging facilities.

“EUV light is tricky to work with,” says Goldberg, “because every material absorbs it so strongly. So instead of glass lenses, EUV optical systems rely mainly on specialized mirrors with atomic-scale smoothness, topped by multilayer coatings for high reflectivity.” To maintain efficiency, the entire optical system has to be placed in a high-vacuum environment.

While the existing eight-year-old microscope at beamline 11.3.2, dubbed the AIT (for Actinic Inspection Tool), has unique imaging capabilities, the fast-moving nature of semiconductor technology means its future is limited. SHARP will exceed its performance in every metric: resolution, speed, uniformity of illumination, and coherence control. SHARP will enable forward-looking research years before commercial tools become available.

Within a few years, semiconductor devices will be measured in dimensions of 16, 11, or 8 nanometers, mere billionths of a meter. To mass-produce them, industry is pushing a photolithography process that uses EUV light with a wavelength of just 13.5 nanometers, 40 times smaller than visible light.

“At this short wavelength, we can print and image circuit patterns at nanometer length scales,” says Goldberg. “The new microscope will leverage years of cutting-edge EUV and soft-x‑ray microscopy experience, experimental systems-engineering at CXRO, and EUV optics expertise developed as part of the lithography research programs here.” Goldberg says that the ALS, as one of the world’s brightest sources of EUV light, “is a great place to develop EUV lithography technologies.”

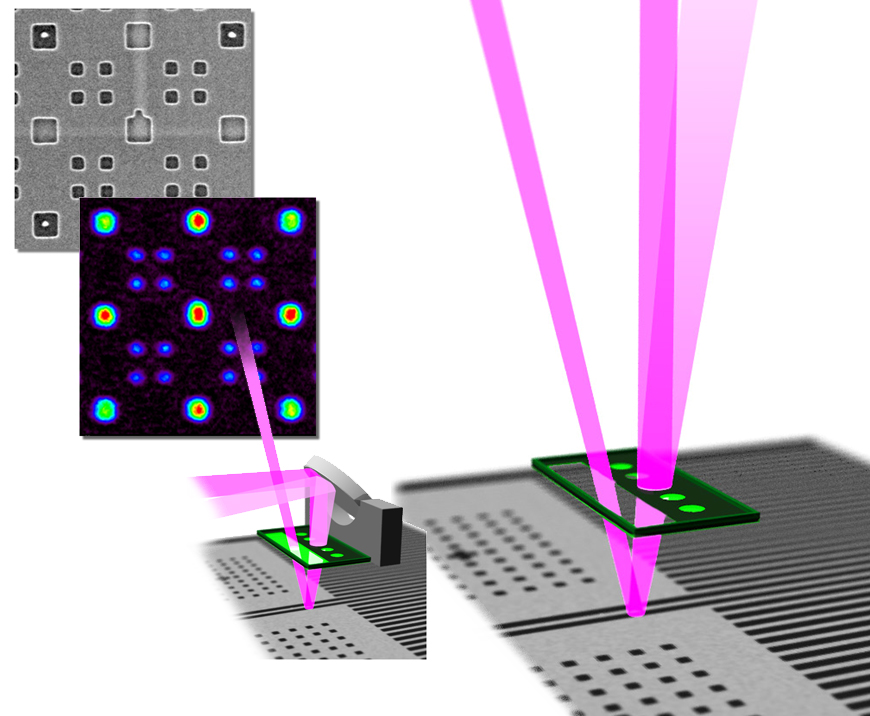

At top are programmed pattern defects, including the large protrusion in the center, developed by a team at IBM to evaluate printing sensitivity. The current AIT microscope’s image of the defects is center left. The final stage of the AIT’s beam path is shown bottom left: the synchrotron’s EUV beam enters from the top, reflects from the mask, is focused by an array of zone plates, and then reflects from a turning mirror to an EUV-sensitive camera, not shown, to the left. The more efficient SHARP beam path at right removes the turning mirror and a window from the array of zone plates to increase brightness. SHARP incorporates other refinements such as a new high-efficiency illuminator, a tunable monochromator that controls the coherence of the light, and a choice of zone plate lenses for different magnifications as the microscope navigates around the mask.

In lithography, photomasks are the key to mass production. A series of photomasks carry the master circuit patterns that are transferred onto a chip, layer by layer, to create working semiconductor devices. The masks are analogous to the negatives in a photographer’s darkroom, or master pages on a photocopier.

Minute imperfections or tiny particles of dust on a master, if not found and cleaned or fixed, ultimately cause chips to fail. Goldberg and his team have shown that defects and patterns can appear very different when viewed with non-EUV inspection tools such as electron microscopes, making EUV microscopy essential for the development of EUV masks because only in this way can damaging dust particles and other defects be identified reliably.

“Other microscopes can have wonderfully high resolution, but they can’t detect the wavelength-specific EUV response of mask patterns and defects,” says Goldberg, “and that’s necessary to make successful repairs.”

SHARP is called an “actinic” microscope because it uses the same EUV wavelengths used in production. Thus the new EUV microscope will enable semiconductor company researchers to better evaluate defects and repair strategies, mask materials and architectures, and advanced pattern features.

Like its predecessor, the SHARP microscope will also feature an array of lenses, side by side, so users can select the different imaging properties they need, much as a common lab microscope mounts different lenses on a rotating turret.

The high-magnification objective lenses for the new microscope are holographic Fresnel zoneplate lenses, microscopic objects produced by CXRO’s Nanowriter. The Nanowriter, under the direction of Erik Anderson, holds the world record for creating the highest resolution zoneplates for many synchrotron and other short-wavelength applications. The lenses are only slightly wider than a single human hair, yet they project high-quality images of the mask surface with up to 2,000 times magnification.

A special feature of the new microscope will be illumination coherence control. The ALS produces an EUV beam with laser-like coherence, ideal for many experiments. For microscopy, however, the image resolution can be improved by a factor of two by carefully re-engineering the illumination into a state called partial coherence. Microscopists have recognized the importance of partial coherence for years, and the synchrotron community is now catching up.

An angle-scanning mirror in the new microscope’s beamline illuminator will take the highly-coherent ALS light and steer it into patterns, like a mini-laser-light show, breaking and re-shaping the coherence properties. In this way, the SHARP microscope will replicate the properties of current and future tools for lithography production and research, giving researchers the most advanced look at what’s to come.

Additional information

With sales of some $51 billion a year, semiconductors are the United States’ second largest export product. Developing technology to produce and test the next generation computer chips is one of the industry’s core missions. For over a decade, semiconductor companies have sponsored photolithography-related research at Berkeley Lab through the Center for X-Ray Optics, including world-leading programs in optics, masks, and materials — most conducted on three CXRO beamlines at the Advanced Light Source. For more information on CXRO, visit http://www.cxro.lbl.gov/. For more information on the ALS visit http://www-als.lbl.gov/.

# # #

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.