When electronic states in materials are excited during dynamic processes, interesting phenomena such as electrical charge transfer can take place on quadrillionth-of-a-second, or femtosecond, timescales. Numerical simulations in real-time provide the best way to study these processes, but such simulations can be extremely expensive. For example, it can take a supercomputer several weeks to simulate a 10 femtosecond process. One reason for the high cost is that real-time simulations of ultrafast phenomena require “small time steps” to describe the movement of an electron, which takes place on the attosecond timescale – a thousand times faster than the femtosecond timescale.

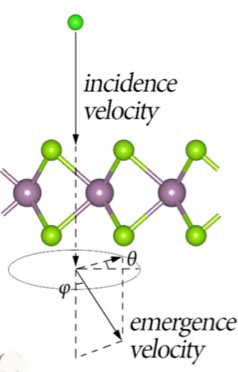

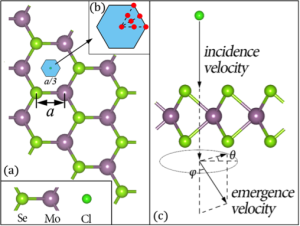

Model of ion (Cl) collision with atomically thin semiconductor (MoSe2). Collision region is shown in blue and zoomed in; red points show initial positions of Cl. The simulation calculates the energy loss of the ion based on the incident and emergent velocities of the Cl.

To combat the high cost associated with the small-time steps, Lin-Wang Wang, senior staff scientist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), and visiting scholar Zhi Wang from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, have developed a new algorithm which increases the small time step from about one attosecond to about half a femtosecond. This allows them to simulate ultrafast phenomena for systems of around 100 atoms.

“We demonstrated a collision of an ion [Cl] with a 2D material [MoSe2] for 100 femtoseconds. We used supercomputing systems for ten hours to simulate the problem – a great increase in speed,” says L.W. Wang. That represents a reduction from 100,000 time steps down to only 500. The results of the study were reported in a Physical Review Letters paper titled “Efficient real-time time-dependent DFT method and its application to a collision of an ion with a 2D material.”

Conventional computational methods cannot be used to study systems in which electrons have been excited from the ground state, as is the case for ultrafast processes involving charge transfer. But using real-time simulations, an excited system can be modeled with time-dependent quantum mechanical equations that describe the movement of electrons.

The traditional algorithms work by directly manipulating these equations. Wang’s new approach is to expand the equations into individual terms, based on which states are excited at a given time. The trick, which he has solved, is to figure out the time evolution of the individual terms. The advantage is that some terms in the expanded equations can be eliminated

“By eliminating higher energy terms, you significantly reduce the dimension of your problem, and you can also use a bigger time step,” explains Wang, describing the key to the algorithm’s success. Solving the equations in bigger timesteps reduces the computational cost and increases the speed of the simulations

Comparing the new algorithm with the old, slower algorithm yields similar results, e.g., the predicted energies and velocities of an atom passing through a layer of material are the same for both models. This new algorithm opens the door for efficient real-time simulations of ultrafast processes and electron dynamics, such as excitation in photovoltaic materials and ultrafast demagnetization following an optical excitation.

The work was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science and used the resources of the National Energy Research Scientific Computing center (NERSC).

Additional Information

For more about the research of Lin-Wang Wang go here: http://cmsn.lbl.gov

For more about NERSC go here: https://www.nersc.gov

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.