In deserts and other arid lands, microbes often form very thin top layers on soil known as biocrusts, which behave a bit like Rip Van Winkle. He removed himself from a stressful environment by sleeping for decades, and awoke to a changed world; similarly, the biocrust’s microbes lie dormant for long periods until precipitation (such as a sudden downpour) awakens them. Understanding more about the interactions between the microbial communities—also called “microbiomes”—in the biocrusts and their adaptations to their harsh environments could provide important clues to help shed light on the roles of soil microbes in the global carbon cycle.

“In support of DOE’s mission to untangle the complexities of the carbon cycle, we’re using the biocrust system to examine the specific metabolites in soil and how microbes target these compounds,” said Trent Northen, a scientist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the U.S. Department of Energy Joint Genome Institute (DOE JGI), a DOE Office of Science User Facility. “Dissolved organic carbon (DOC) and soil microbes are typically studied as broad groups, and we wanted to examine the specific relationship between the diversity of soils metabolites and the diversity of microbes.”

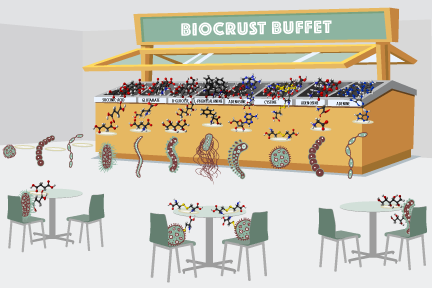

The Berkeley Lab team examined the diversity of molecules in a biological soil crust (“buffet”) and then used exometabolomics to study how bacteria isolated from this soil deplete (“eat”) specific molecules. This is analogous to looking at how the buffet is changed after each type of bacteria has eaten its fill. They found that these isolates each target a small and largely non-overlapping fraction of the available molecules. This suggested to the researchers that co-localized microbes avoid eating each other’s lunch. (Art credit: Zosia Rostomian, Berkeley Lab)

In a study published Sept. 22 in Nature Communications, a team led by Northen used seven bacterial isolates from desert biocrusts, one of them the cyanobacterium Microcoleus vaginatus –sequenced by the DOE JGI—that had been the focus of earlier work. The isolates were cultivated in what Northen describes as “a virtual smorgasbord” of metabolites containing almost 500 compounds until they stopped growing. Northen and his collaborators deployed a set of tools that he calls “exometabolomics” which harnesses the analytical capabilities of the latest mass spectrometry techniques to quantitatively measure how each microbes and the biocrust community transforms complex mixtures of metabolites, in this case, from soil.

Community chowdown: the biocrust buffet

“Traditionally, researchers have applied broad categories when studying soil carbon and microbes, like grouping the foods and people at a buffet into broad groups and measuring the total calories each group of people eats,” said Northen. “But people at a buffet don’t all eat the same things; vegetarians won’t touch the meats, others are allergic to gluten and so on. In the same way, the biocrusts are a big buffet and we find in our study that they each use different fractions of DOC, so it takes a community to consume a buffet.”

“We were surprised to find that the diverse microbes we examined each targeted specific metabolites, where individual isolates only used a small range—13-26 percent—of the metabolites,” says the study’s first author Richard Baran also from Berkeley Lab. Even more surprising to the research team was the lack of overlap in the microbes’ substrate preferences, where only a few metabolites were consumed by all.

“This may be an important mechanism to help support diverse microbes in soil,” said Northen. “If each type of microbes targets unique metabolites they could avoid pure competition by specialization, yet in aggregate they metabolize complex carbon pools. By eating different items on the menu, the metabolites could be helping to support more microbial diversity.”

Another observation Northen noted from these results is that in many cases, metabolites that are found to be released by one microbe are consumed by another. The discovery suggests that there may be a food web in the biocrusts microbiomes in which individual microbes may depend on each other for specific metabolites. “Essentially, microbes won’t eat each other’s lunch if they depend on the other for a specific metabolite,” Northen said, describing this possible mechanism in support of soil biodiversity.

Linking genomics with microbial metabolism

Though the biocrusts that the team focused on in this paper comprise a fairly simple model system, they say they plan to apply exometabolomics to more complex soil systems and more microbes. “What we’re really trying to define is what is the connection between the diversity of metabolites and microbial diversity? What are the specific compounds, and how are those specific compounds transformed by specific microbes,” said Northen. “This is exometabolomics.”

The team’s long-term goal is to develop exometabolomics as a predictive tool. By linking sequence data with soil carbon cycling, Northen said, researchers could, for example, take a metagenome and predict what metabolites are present in the environment.

“This novel application of metabolomics to microbial ecology,” said Ferran Garcia-Pichel, Dean of Natural Sciences, College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Arizona State University and one of the paper’s senior authors, “is especially exciting because it brings about the potential to directly link modern genomic advances with much of the traditional knowledge of microbial metabolism, with added value to both.”

This work was supported under a DOE Office of Science Early Career Research Program grant (http://science.energy.gov/early-career) and through ENIGMA – Ecosystems and Networks Integrated with Genes and Molecular Assemblies – a multi-institutional consortium funded by the DOE Office of Science and managed by Berkeley Lab. (http://enigma.lbl.gov/). It is the result of a long-term institutional collaboration between ASU and Berkeley Lab. The biocrust research described in the publication described above, complements ongoing efforts in the study of global carbon management subsumed under Berkeley Lab’s Microbes-to-Biomes Initiative: http://m2b.lbl.gov/.

Northen talked about this project in 2011 as part of Berkeley Lab’s “Secrets of the Soil” panel:

# # #

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov/.