With emerging exascale supercomputers, researchers will soon be able to accurately simulate the ground motions of regional earthquakes quickly and in unprecedented detail, as well as predict how these movements will impact energy infrastructure—from the electric grid to local power plants—and scientific research facilities.

Currently, an interdisciplinary team of researchers from the Department of Energy’s (DOE’s) Lawrence Berkeley (Berkeley Lab) and Lawrence Livermore (LLNL) national laboratories, as well as the University of California at Davis are building the first-ever end-to-end simulation code to precisely capture the geology and physics of regional earthquakes, and how the shaking impacts buildings. This work is part of the DOE’s Exascale Computing Project (ECP), which aims to maximize the benefits of exascale—future supercomputers that will be 50 times faster than our nation’s most powerful system today—for U.S. economic competitiveness, national security and scientific discovery.

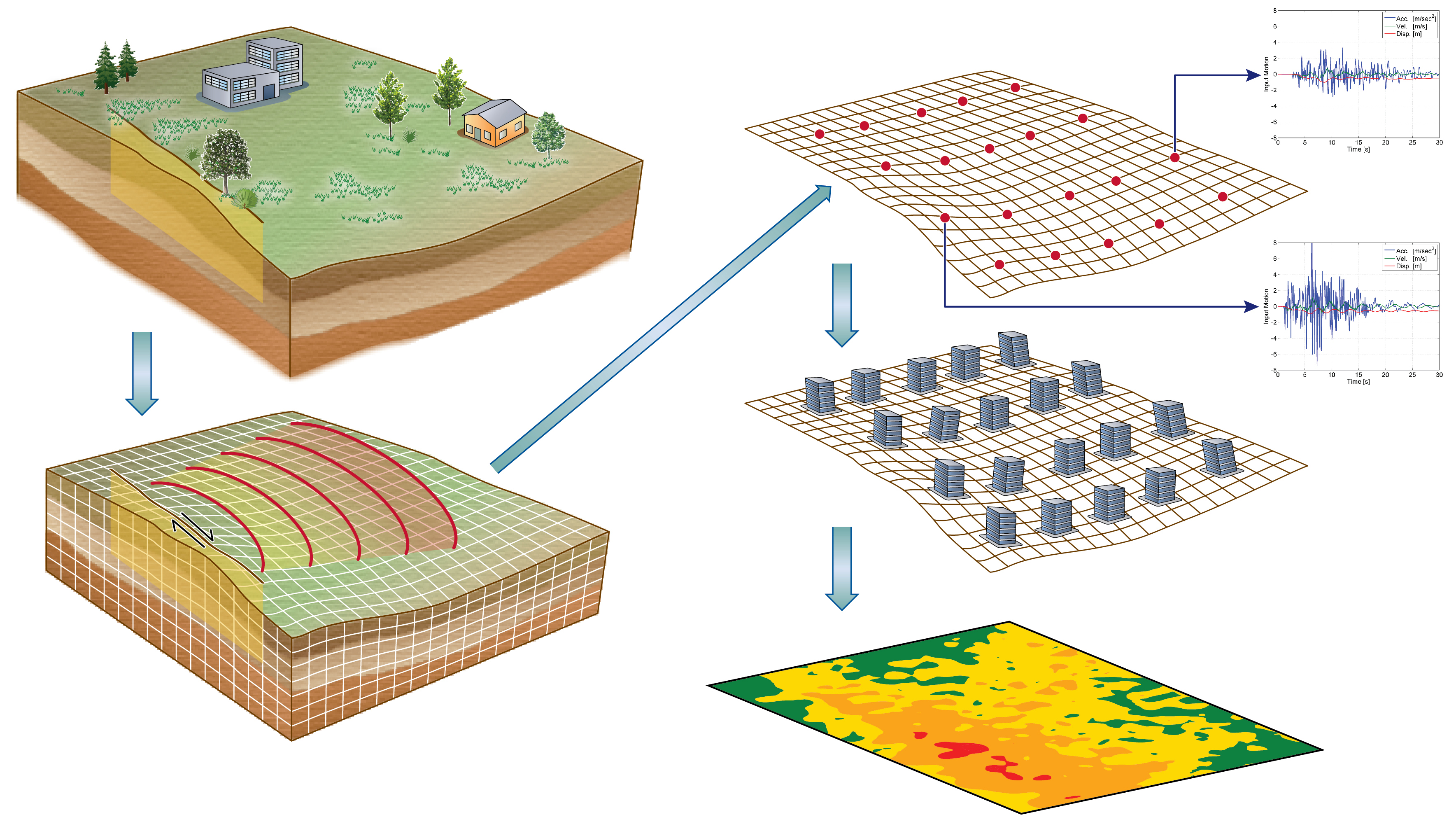

Transforming hazard into risk: Researchers at Berkeley Lab, LLNL and UC Davis are utilizing ground motion estimates from a regional-scale geophysics model to drive infrastructure assessments. (Image Courtesy of David McCallen)

“Due to computing limitations, current geophysics simulations at the regional level typically resolve ground motions at 1-2 hertz (vibrations per second). Ultimately, we’d like to have motion estimates on the order of 5-10 hertz to accurately capture the dynamic response for a wide range of infrastructure,” says David McCallen, who leads an ECP-supported effort called High Performance, Multidisciplinary Simulations for Regional Scale Seismic Hazard and Risk Assessments. He’s also a guest scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth and Environmental Sciences Area.

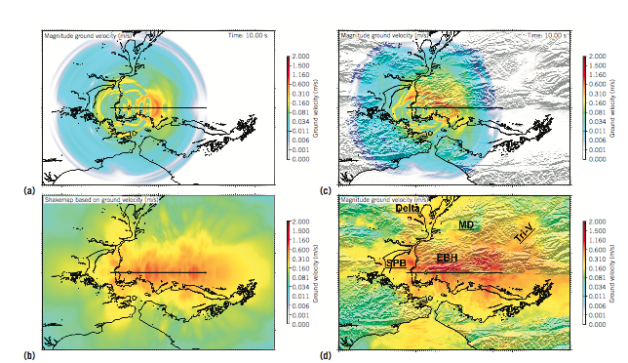

One of the most important variables that affect earthquake damage to buildings is seismic wave frequency, or the rate at which an earthquake wave repeats each second. Buildings and structures respond differently to certain frequencies. Large structures like skyscrapers, bridges, and highway overpasses are sensitive to low frequency shaking, whereas smaller structures like homes are more likely to be damaged by high frequency shaking, which ranges from 2 to 10 hertz and above. McCallen notes that simulations of high frequency earthquakes are more computationally demanding and will require exascale computers.

In preparation for exascale, McCallen is working with Hans Johansen, a researcher in Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division (CRD), and others to update the existing SW4 code—which simulates seismic wave propagation—to take advantage of the latest supercomputers, like the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center’s (NERSC’s) Cori system. This manycore system contains 68 processor cores per chip, nearly 10,000 nodes and new types of memory. NERSC is a DOE Office of Science national user facility operated by Berkeley Lab. The SW4 code was developed by a team of researchers at LLNL, led by Anders Petersson, who is also involved in the exascale effort.

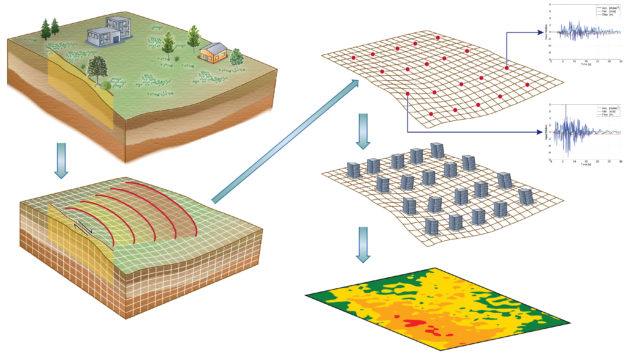

Simulated ground motions for an M 7.0 Hayward Fault earthquake showing (a) the magnitude of ground velocity at 10 s, (b) ShakeMap based on peak ground velocity for the 1D model, and (c) and (d) the same for the 3D model. Geologic features are Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta (Delta); East Bay Hills (EBH); Mount Diablo (MD); San Pablo Bay (SPB); and Dublin-Pleasanton- Livermore Tri-Valley (Tri-V). (Image Courtesy of David McCallen)

With recent updates to SW4, the collaboration successfully simulated a 6.5 magnitude earthquake on California’s Hayward fault at 3-hertz on NERSC’s Cori supercomputer in about 12 hours with 2,048 Knights Landing nodes. This first-of-a-kind simulation also captured the impact of this ground movement on buildings within a 100-square kilometer (km) radius of the rupture, as well as 30km underground. With future exascale systems, the researchers hope to run the same model at 5-10 hertz resolution in approximately five hours or less.

“Ultimately, we’d like to get to a much larger domain, higher frequency resolution and speed up our simulation time, ” says McCallen. “We know that the manner in which a fault ruptures is an important factor in determining how buildings react to the shaking, and because we don’t know how the Hayward fault will rupture or the precise geology of the Bay Area, we need to run many simulations to explore different scenarios. Speeding up our simulations on exascale systems will allow us to do that.”

This work was published in the recent issue of Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) Computer Society’s Computers in Science and Engineering.

Predicting Earthquakes: Past, Present and Future

Historically, researchers have taken an empirical approach to estimating ground motions and how the shaking stresses structures. So to predict how an earthquake would affect infrastructure in the San Francisco region, researchers might look at a past event that was about the same size—it might even have happened somewhere else—and use those observations to predict ground motion in San Francisco. Then they’d select some parameters from those simulations based on empirical analysis and surmise how various buildings may be affected.

“It is no surprise that there are certain instances where this method doesn’t work so well,” says McCallen. “Every single site is different—the geologic makeup may vary, faults may be oriented differently and so on. So our approach is to apply geophysical research to supercomputer simulations and accurately model the underlying physics of these processes.”

To achieve this, the tool under development by the project team employs a discretization technique that divides the Earth into billions of zones. Each zone is characterized with a set of geologic properties. Then, simulations calculate the surface motion for each zone. With an accurate understanding of surface motion in a given zone, researchers also get more precise estimates for how a building will be affected by shaking.

The team’s most recent simulations at NERSC divided a 100km x 100km x 30km region into 60 billion zones. By simulating 30km beneath the rupture site, the team can capture how surface-layer geology affects ground movements and buildings.

Eventually, the researchers would like to get their models tuned up to do hazard assessments. As Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) begins to implement a very dense array of accelerometers into their SmartMeters—a system of sensors that collects electric and natural gas use data from homes and businesses to help the customer understand and reduce their energy use—McCallen is working with the utility company about potentially using that data to get a more accurate understanding of how the ground is actually moving in different geologic regions.

“The San Francisco Bay is an extremely hazardous area from a seismic standpoint and the Hayward fault is probably one of the most potentially risky faults in the country,” says McCallen. “We chose to model this area because there is a lot of information about the geology here, so our models are reasonably well-constrained by real data. And, if we can accurately measure the risk and hazards in the Bay Area, it’ll have a big impact.”

Utilizing ground motions to evaluate regional infrastructure risk with the Hayward Fault rupture scenario and resulting demands/ risk on representative buildings (in terms of peak interstory drift). (Image courtesy of David McCallen

He notes that the current seismic hazard assessment for Northern California identifies the Hayward Fault as the most likely to rupture with a magnitude 6.7 or greater event before 2044. Simulations of ground motions from large—magnitude 7.0 or more—earthquakes require domains on the order of 100-500 km and resolution on the order of about one to five meters, which translates into hundreds of billions of grid points. As the researchers aim to model even higher frequency motions between 5 to 10 hertz, they will need denser computational grids and finer time-steps, which will drive up computational demands. The only way to ultimately achieve these simulations is to exploit exascale computing, McCallen says.

In addition to leading an ECP project, McCallen is also a Berkeley Lab research affiliate and Associate Vice President at the University of California Office of the President.

This work was done with support from the Exascale Computing Project, a collaborative effort between the DOE’s Office of Science and National Nuclear Security Agency. NERSC is a DOE Office of Science User Facility.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.