The average global energy consumption of transportation fuels is currently several terawatts (1 terawatt = 1012 Joule per second). A major scientific gap for developing a solar fuels technology that could replace fossil resources with renewable ones is scalability at the unprecedented terawatts level. In fact, the only existing technology for making chemical compounds on the terawatt scale is natural photosynthesis.

The two reactions necessary to complete the photosynthetic cycle—CO2 reduction and H2O oxidation—take place in incompatible environments, so they have to be physically separated by a barrier. But, for the process to be efficient, the distance between the two should be as short as possible—on the nanometer scale. Natural photosynthetic systems accomplish this very well, but it presents an engineering challenge for fabricating artificial photosystems based on this design, explained Heinz Frei, a senior scientist in Biosciences’ Molecular Biophysics and Integrated Bioimaging (MBIB) Division.

Frei collaborated with Eran Edri, a former postdoctoral fellow in MBIB now at Ben-Gurion University, and Shaul Aloni at the Molecular Foundry, a DOE Office of Science User Facility. They developed a fabrication method to make a square-inch sized artificial photosystem, in the form of an inorganic core-shell nanotube array, that implements this design principle for the first time. “This achievement is made possible by the unique synergy of biophysical, chemical, and nanomaterials expertise of MBIB, thus contributing to the Division’s scientific advances towards solving a major national challenge in energy,” Frei said.

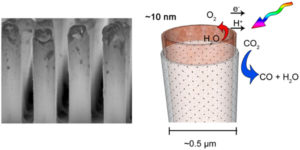

The method, described in a paper published earlier this year in ACS Nano, employs a silicon rod array as a template in combination with atomic layer deposition and cryo-etching techniques to provide control of the characteristic length scales of the components over eight orders of magnitude. While the array is fabricated on the macroscale, the diameter of individual tubes is a few hundreds of nanometers and the wall thickness a few tens of nanometers.

The inside surfaces of the cobalt oxide nanotubes provide the catalytic site for H2O oxidation, which are separated from the light absorber and sites of CO2reduction on the outside by an ultrathin dense phase silica layer. The latter acts as a proton-conducting, O2-impermeable membrane. Somewhat surprising was the finding that, despite seemingly incompatible synthesis conditions, it was indeed possible to assemble a solid oxide-based nanoscale construct with embedded “soft” organic molecular wires for electron conduction and end up with all components intact, noted Frei.

The inside surfaces of the cobalt oxide nanotubes provide the catalytic site for H2O oxidation, which are separated from the light absorber and sites of CO2reduction on the outside by an ultrathin dense phase silica layer. The latter acts as a proton-conducting, O2-impermeable membrane. Somewhat surprising was the finding that, despite seemingly incompatible synthesis conditions, it was indeed possible to assemble a solid oxide-based nanoscale construct with embedded “soft” organic molecular wires for electron conduction and end up with all components intact, noted Frei.

The nanotube array provides a basis for the development of scalable engineered solar fuels systems suitable for deployment on abundant, non-arable land.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.