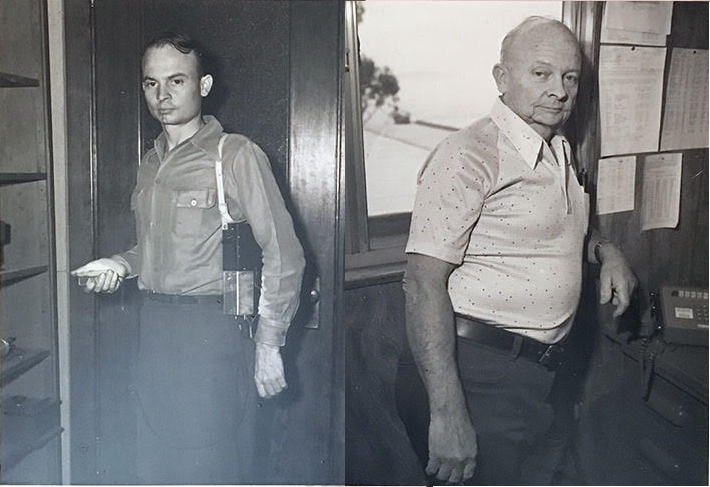

William R. “Bill” Baker, Berkeley Lab’s first electrical engineer, at the Lab in 1940 (left) and in 1980, the year he retired from the Lab. (Photo courtesy of Bill Baker’s family)

William R. “Bill” Baker, who died May 4 at age 103, was a lifelong engineer with an unrelenting mind and boundless ingenuity. He was the first electrical engineer hired by Ernest Orlando Lawrence, the namesake of the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab).

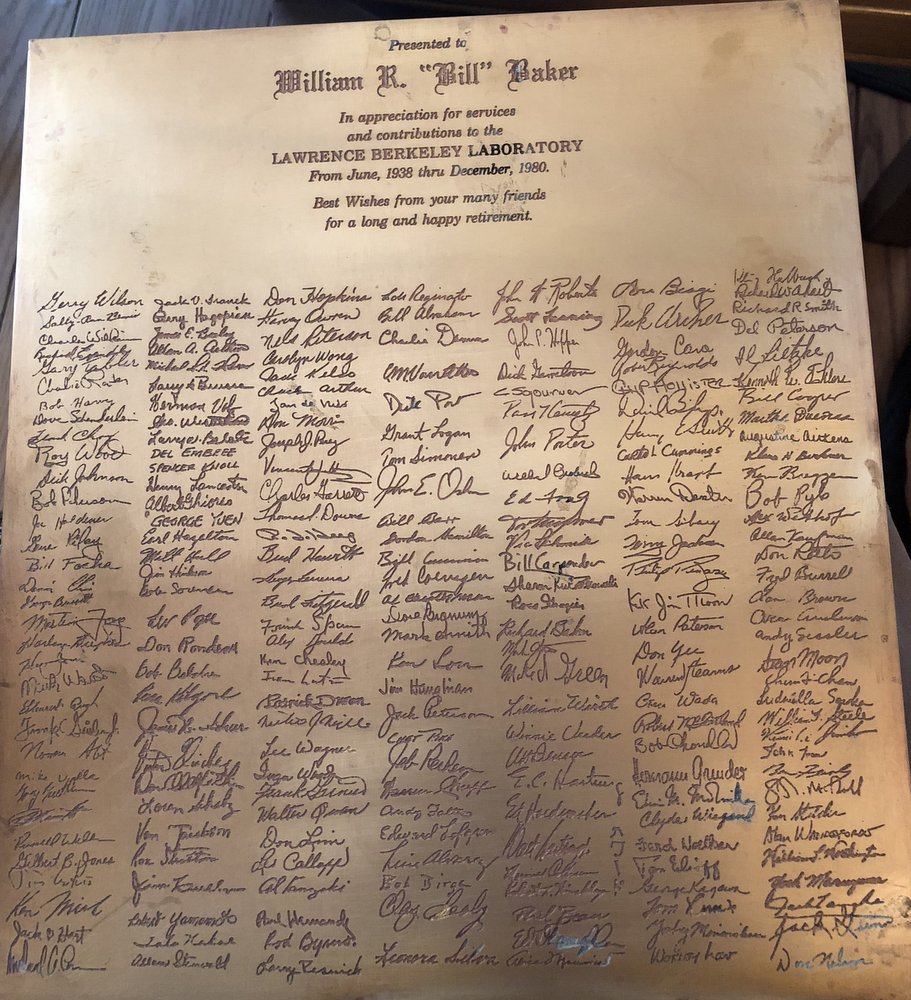

As an engineering student at UC Berkeley, Baker was hired in June 1938 to work at Lawrence’s Radiation Laboratory (also known as the Rad Lab), the predecessor to Berkeley Lab. It was the start of a long and productive Lab career that would span more than 42 years and would closely mirror the history of the Lab itself.

A young Bill Baker on the grounds now known as Berkeley Lab. (Photo courtesy of Bill Baker’s family)

He would work on technologies to support the Lab’s successively larger particle accelerators, called cyclotrons.

When Lawrence’s cyclotron designs ultimately outgrew the Radiation Laboratory buildings on the UC Berkeley campus, Baker went to work on a massive, 184-inch cyclotron at a site that is now Berkeley Lab’s permanent home.

Bill Baker, left, at the controls of the 60-inch cyclotron that was built on the UC Berkeley campus near LeConte Hall. This 1945 photo was featured in a Smithsonian exhibit. (Credit: UC Berkeley)

‘The epitome of the American Dream’

“He is the epitome of the American Dream,” recalled Candace Baker, his youngest daughter who resides in Utah. “What a brilliant mind he had, and yet he was so humble and kind.”

Born in a dirt-floored log cabin in Arkansas in June 1914 and raised in the Oklahoma oil fields, Baker train-hopped to California in search of new opportunities. His interest in science and engineering had been inspired in his youth by science-fiction magazines such as Hugo Gernsback’s Amazing Stories – he even kept a journal noting his favorite short stories from their pages.

Baker spent several years in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), with a stint in Death Valley as a photographer. He had been sending the money from his multiple tours in the CCC to his mother back home, but she didn’t spend it. She saved it up and returned it to him to pay for his UC Berkeley tuition.

It was while he was a student at UC Berkeley that he had met his wife-to-be, Edna. She was waitressing at the Jolly Roger restaurant in Berkeley at the time (the Jolly Roger is, as it just so happens, the English moniker for a flag flown by pirate ships, but more about his pirate leanings later), and he proposed to her on their third date. They married soon after, and they had four children: three daughters and a son.

When Lawrence hired him, the world was in turmoil. The U.S. had yet to emerge from the Great Depression, and Nazi Germany was expanding its reach in Europe. By the time the U.S. entered World War II, the Manhattan Project – which was tasked with developing a nuclear weapon – was already underway.

Group photo, taken in 1944, at the site of the Lab’s 184-inch cyclotron, now home to the Advanced Light Source synchrotron. Bill Baker is the 11th person from the left in the second row from the bottom, with arms crossed. Ernest Lawrence is seated in the bottom row (fifth from the left). (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

The Manhattan Project and the postwar years

Work on the Lab’s 184-inch cyclotron had been halted during the war years, and Baker answered the call to join the Manhattan Project, traveling regularly to Oak Ridge, Tenn.

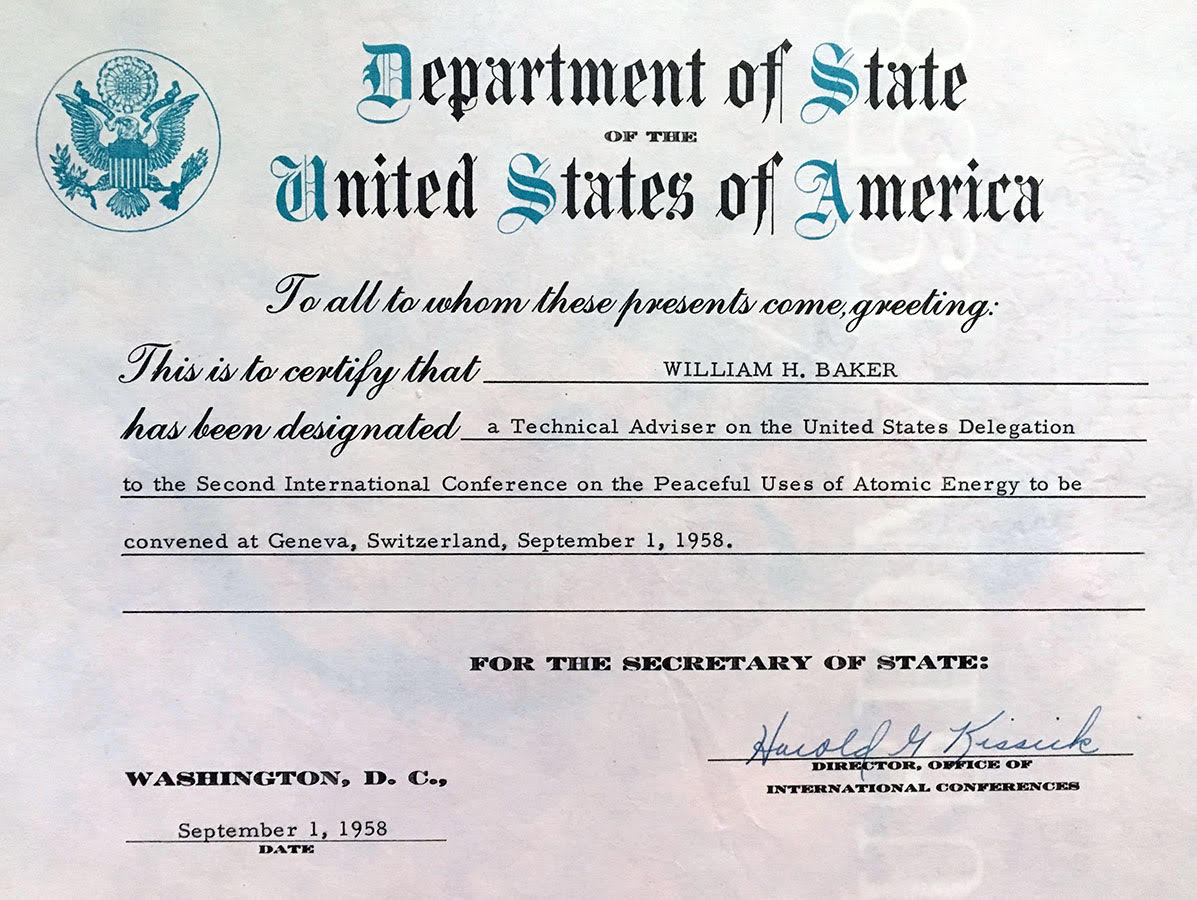

In 1958, Baker was an adviser to the U.S. Delegation attending an International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy. (Image courtesy of Bill Baker’s family)

After the war, Baker was passionate about finding peaceful applications for nuclear science and was deeply involved in fusion energy research. He had served as a technical adviser to the U.S. Delegation attending the Second International Conference on the Peaceful Uses of Atomic Energy in Geneva, Switzerland in September 1958.

“He was absolutely convinced that my mom would have a safe nuclear iron,” said his middle daughter, Joyce Shon, a Berkeley-born artist and art instructor who had an earlier career in construction.

Jim Galvin, a senior technical associate in the Lab’s Engineering Division who was hired in 1971 to work on a small team led by Baker, recalled Baker’s noteworthy problem-solving skills. They worked together on the Neutral Beam Project – a high-power ion source that would serve as a fuel injector and heater for fusion experiments. Baker designed the electronics that Galvin helped to build and test.

They tested a high-power, superfast switch to turn the device’s power supply on and off, and Galvin recalled how they pushed the system’s limits – the electrical current they sent surging through the system created a magnetic force so strong that it caused a heavy welding cable to “jump off the floor … and once lassoed the drill press.” He added, “But the switch worked fine.”

“His work really engaged him totally,” Shon said. “He was fortunate that he really loved what he did.” His life was about work and family, and it was a really exciting time for the field he was in.” She recalled the familiar sight of her father heading off to work in the mornings wearing a signature clip-on bow tie.

Baker kept his work and home life separate, and there were times when it seemed his devotion to work had the upper edge, she noted.

“He was always sitting, with his glasses on his nose, working on things. He had a very active brain. He was really determined: He would sink his teeth into something and he wouldn’t let go until he figured it out. His mind was his hobby.”

An active and inventive mind

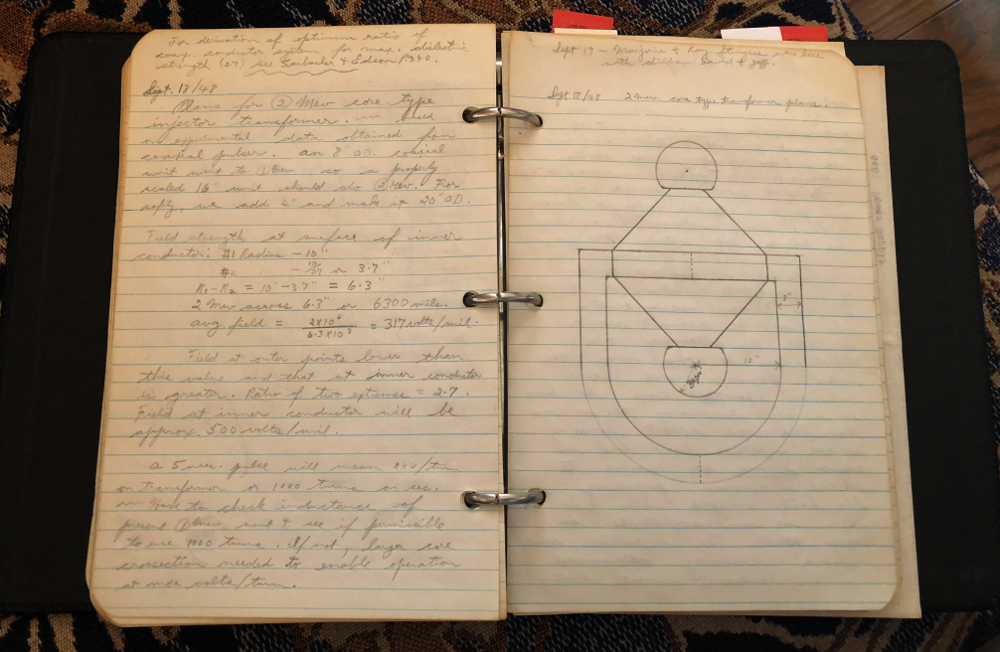

Over the course of his career Baker would log about 50 patents to his name. Shon flipped through a binder he kept with all of his patent documents and read off a few names: “high-voltage multiple core transformer,” “beam-current integrator,” “apparatus for producing and purifying plasma.”

A 1980 profile in Berkeley Lab’s “Currents” newsletter quotes Baker: “All of my patents have been in response to the needs of projects I’ve worked on over the years. It reminds me of that old sign on the cement truck: Find a need and fill it.”

He added, jokingly, “I’m always enthusiastic about my ideas, until I discover what’s wrong with them.” In the same article, he expressed support for Lawrence’s view that things discovered at the Lab “should be kept in the public domain, free for all to use.”

Baker’s family inherited boxes of handwritten notebooks – neatly detailed with sketches, equations, and measurements – and other files documenting Baker’s work and hobbies through the years.

Baker had also contributed a substantial number of files that are now stored at the National Archives, with topics ranging from accelerator and fusion energy R&D to advanced particle detector components including photomultipliers and scintillators, and electrical devices such as capacitors and oscillators.

“I don’t think he ever met a gauge or a thermometer or a measuring device that he didn’t love,” Shon said.

Once an engineer, always an engineer

Family members noted how Baker had used his engineering know-how at home. He built a sun-tracking solar-energy system to power a backyard fountain – Shon found Baker’s notes dating back to the 1940s on his solar-panel concepts.

“He made his own automatic sprinkler system before they were sold commercially,” Candace Baker said, “and he perfected a solar oven and a pan for cooking cakes in the microwave. He was always in pursuit of making things simpler.”

Shon said, “He went through a lot of parts and theories and explosions in the microwave during the course of that.”

Baker also built a small cannon, driven by an acetylene tank, that he used on occasion to fire apples from one of his trees toward a nearby reservoir.

Bill Baker takes the wheel during the 2014 Pirate Festival at the Vallejo waterfront. (Photo courtesy of Bill Baker’s family)

Shon noted that the family rolled the small cannon (complete with flour-loaded toilet paper cardboard tubes to simulate gunpowder smoke) aboard a sailboat during a pirate festival Baker participated in at the Vallejo waterfront in 2014. Baker, who turned 100 that year, donned a feathered pirate hat and adopted the pirate name “Billy Bones” for the event.

Sailing was a hobby that Baker had taken up early in his Lab career. He owned a share of a 16-foot sailboat at the Berkeley Marina called The Fern, and eventually became its sole owner.

In retirement, Baker kept in touch with his fellow Lab retirees. He would often attend monthly retirement lunches at a restaurant near the Berkeley waterfront.

“He was pretty intrigued by the realm of physics,” Shon said, and puzzled over mysteries involving theories of gravity and time. “He had subscriptions to science journals, and he liked following some of the government research,” she said, and was an avid follower of news related to the Mars rover program.

On longevity and happiness: ‘Drink more root beer floats’

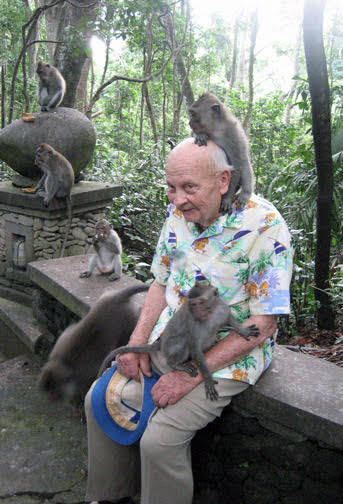

Baker, whose Lab work allowed him to travel to Australia, England, and France, also enjoyed traveling after retirement. “He traveled with family until he was 101, enjoying trips to Turkey, Bali, Mexico, and Crete,” Shon said. He was known to often indulge his cravings for ice cream and Reuben sandwiches.

“My Dad was an amazing man,” Shon said. “His life was quite an incredible journey for a fellow who was born in a dirt-floored log cabin in Arkansas and rode the rails during the Depression looking for a better life. I’d say he succeeded.”

She added, “If you want to live a long and happy life, Dad would probably say, ‘Do what makes you happy, don’t worry about stuff, and drink more root beer floats.’”

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit the Office of Science website at science.energy.gov.