New supercomputer simulations by climate scientists at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have shown that climate change intensified the amount of rainfall in recent hurricanes such as Katrina, Irma, and Maria by 5 to 10 percent. They further found that if those hurricanes were to occur in a future world that is warmer than present, those storms would have even more rainfall and stronger winds.

The study, “Anthropogenic Influences on Major Tropical Cyclone Events,” will be published November 15 in the journal Nature. To reach their conclusions Berkeley Lab researchers Christina Patricola and Michael Wehner modeled 15 historical tropical cyclones, or hurricanes, as they are called in the Atlantic, and simulated them in various past and projected future climate scenarios. The purpose of the study was to examine how warming caused by human activities may have impacted these storms and could affect similar storms in the future.

“We’re already starting to see anthropogenic factors influencing tropical cyclone rainfall,” said Patricola, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Earth and Environmental Sciences Area and lead author of the study. “And our simulations strongly indicate that as time goes on we can expect to see even greater increases in rainfall.”

Berkeley Lab researcher Christina Patricola is lead author of a new study that projects wetter, windier tropical cyclones as the climate warms. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

Patricola chose 15 tropical cyclones that have occurred over the last decade across the globe – including the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans – and ran high-resolution climate simulations of those storms in different scenarios, varying factors such as air and ocean temperatures, humidity, and greenhouse gas concentrations. “It is difficult to unravel how climate change may be influencing tropical cyclones using observations alone because records before the satellite-era are incomplete and natural variability in tropical cyclones is large,” she said.

She split the study into two parts, one to analyze the effects of climate change so far, and the second to project into the future, to understand how various levels of global warming could change tropical cyclone intensity and rainfall.

She found that a warming climate has already made rainfall more intense, by 5 to 10 percent, but has so far not appreciably impacted wind speeds in the hurricanes considered in this study. However if the climate continues to warm, peak wind speeds could increase by as much as 25 knots, or about 29 mph.

‘Hindcast’ attribution method

The researchers used what Wehner, an extreme weather expert in Berkeley Lab’s Computational Research Division, calls the hindcast attribution method, which he describes as the same as a forecast, except that the event has already happened “so you potentially have more information to use.”

Wehner and Patricola used the same method last year in an analysis of a severe 2013 Colorado storm that caused record flooding. “You can certainly use your expert judgment in a better way after the fact,” he said. “So you simulate the event in the world that was, followed by simulating a counterfactual storm in a world that might’ve been had humans not modified the climate system.”

For example, by modeling Hurricane Katrina in a pre-industrial climate and again under current conditions, and taking the difference between the results, researchers can determine what can be attributed to anthropogenic warming. However, the design of the study did not allow the researchers to examine the question of whether hurricanes will become more frequent, or whether they will move differently, such as the way Hurricane Harvey stalled for several days over Houston.

Wehner also cautions that only one climate model was used (the Weather Research and Forecasting model, developed by the National Center for Atmospheric Research), and that confidence will be increased when the results are replicated in other models.

More rain, stronger winds

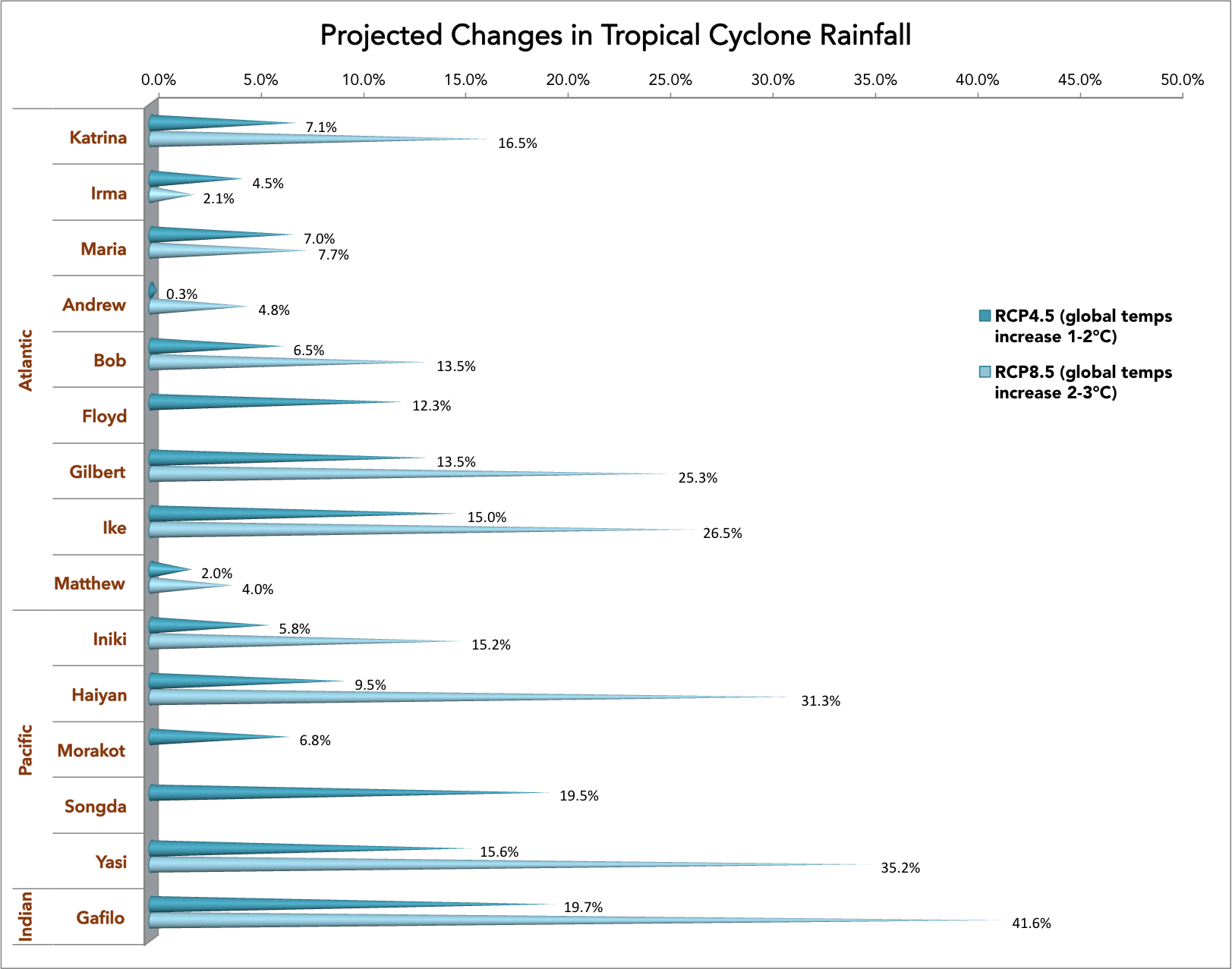

Berkeley Lab researchers simulated 15 tropical cyclones in the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans in three future scenarios, including RCP4.5 and RCP8.5, 10 times each at 4.5 km resolution. The chart shows average percentage increase in rainfall. (Credit: Berkeley Lab) [click on image to view larger]

They found that rainfall could increase 15 to 35 percent in the future scenarios. Wind speeds increased by as much as 25 knots, although most hurricanes saw increases of 10 to 15 knots. “The fact that almost all of the 15 tropical cyclones responded in a similar way gives confidence in the results,” Patricola said.

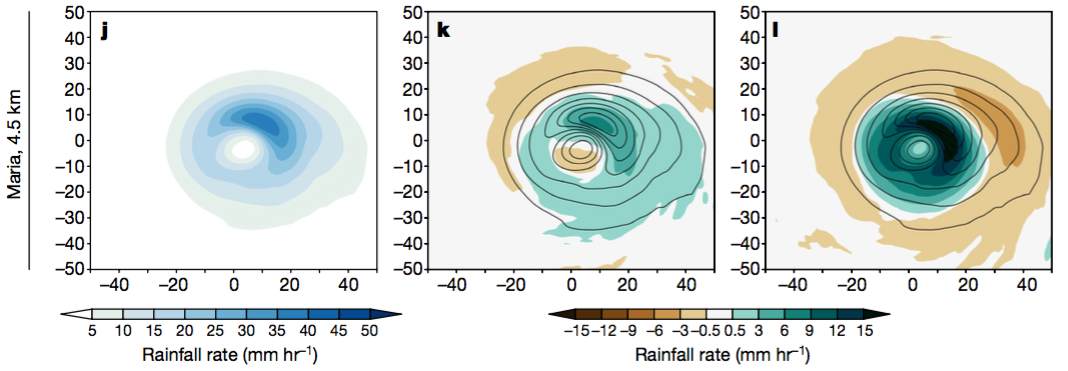

Another interesting finding was that the structure of storms may change where rainfall is more intense in the eye of the hurricane but less intense on the outer edges. “In a warmer world the inner part of the storm is robbing moisture from the outer part of storm,” Wehner said.

The computer simulation on the left shows the rainfall intensity of Hurricane Maria under actual conditions. The other images show how much anthropogenic warming already has impacted rainfall intensity (middle) and its projected impact in a warmer climate (RCP8.5). Green areas indicate heavier rain while brown areas mean less rain. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

Current state-of-the-art long-term climate simulations are approaching resolutions of 25 kilometers and finer, which can broadly represent tropical cyclones. However, important finer-scale features such as cloud clusters can only be approximated at that scale, with unknown implications for climate projections. This motivated the Berkeley Lab team to run their simulations at a resolution of 4.5 kilometers, which allowed some representation of cloud clusters. They found that the finer spatial scale did not alter the qualitative aspects of their conclusions.

“We found that the climate change influences on the wind and rainfall of Hurricane Katrina are insensitive to model resolution between 3 km and 25 km,” Patricola said. “This is good news because it suggests we can place more confidence in projections from global climate models at resolutions of at least 25 km, which are becoming more common.”

With 15 hurricanes simulated in five climate scenarios, each one repeated 10 times, the study used millions of computing hours on the Cori supercomputer at Berkeley Lab’s National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center. “NERSC was absolutely crucial in being able to get this research done,” Patricola said. “Some studies have looked at how individual storms may have changed due to climate change. One of the important things about this study is that we were able to use the same climate model and methodology for 15 storms, which allows us to assess how robust the results are, and had never been done before.”

Patricola emphasizes the importance of using both observations and climate models to understand the climate system. Several studies, including one from Berkeley Lab [published last year in Geophysical Research Letters], found that climate change increased the rainfall from Hurricane Harvey, based on statistical analysis of observations. “When both approaches agree, we can have more confidence in the results,” she said. “Scientists are coming to a consensus that global warming will lead to increases in rainfall from tropical cyclones. One of the remaining uncertainties is how much.”

This study was supported by DOE’s Office of Science as part of the CASCADE Scientific Focus Area. NERSC is a DOE Office of Science user facility at Berkeley Lab.

# # #

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.