The actinides make up the bottom row of the periodic table. (Elements outlined in black were discovered at Berkeley Lab.) (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

The actinides – those chemical elements on the bottom row of the periodic table – are used in applications ranging from medical treatments to space exploration to nuclear energy production. But purifying the target element so it can be used, by separating out contaminants and other elements, can be difficult and time-consuming.

Now researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have developed a new separation method that is vastly more efficient than conventional processes, opening the door to faster discovery of new elements, easier nuclear fuel reprocessing, and, most tantalizing, a better way to attain actinium-225, a promising therapeutic isotope for cancer treatment.

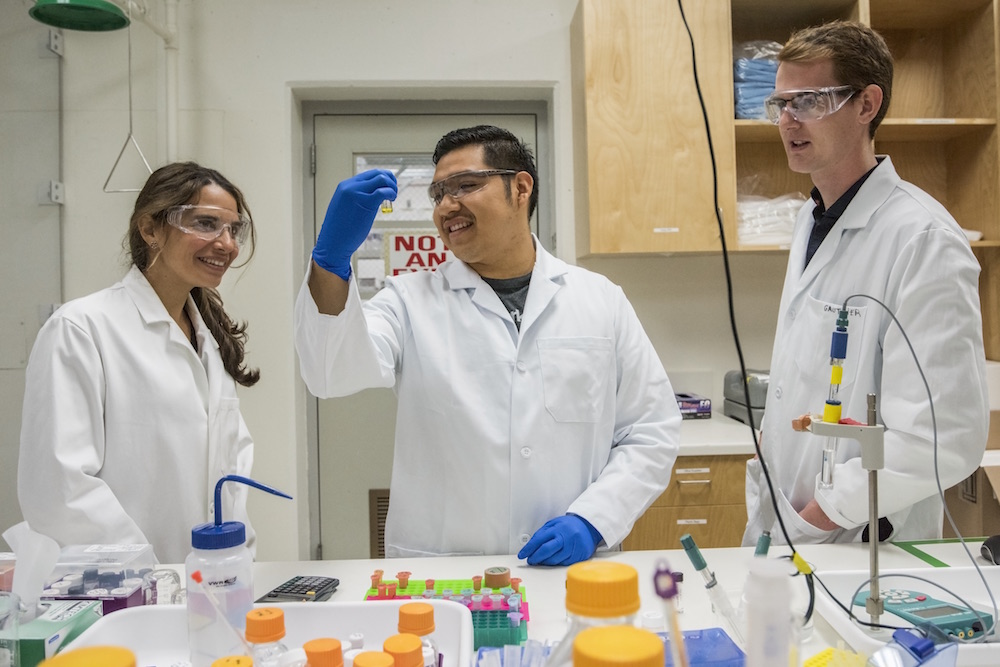

The research, “Ultra-Selective Ligand-Driven Separation of Strategic Actinides,” has been published in the journal Nature Communications. The authors are Gauthier Deblonde, Abel Ricano, and Rebecca Abergel of Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division. “The proposed approach offers a paradigm change for the production of strategic elements,” the authors wrote.

“Our proposed process appears to be much more efficient than existing processes, involves fewer steps, and can be done in aqueous environments, and therefore does not require harsh chemicals,” said Abergel, who is lead of Berkeley Lab’s Heavy Element Chemistry group and also an assistant professor in UC Berkeley’s nuclear engineering department. “I think this is really important and will be useful for many applications.”

(From left) Rebecca Abergel, Abel Ricano, and Gauthier Deblonde of Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division have pioneered a faster method of purifying elements. (Credit: Marilyn Chung/Berkeley Lab)

Berkeley Lab is one of a handful of institutions around the world studying the nuclear and chemical properties of the heaviest elements. Most of them were, in fact, discovered at Berkeley Lab in the last century. Abergel’s group has previously published discoveries on berkelium and plutonium and treatments for radioactive contamination.

Abergel noted that the new separation method achieves separation factors that are many orders of magnitude higher than current state-of-the-art methods. The separation factor is a measure of how well an element can be separated from a mixture. “The higher the separation factor, the fewer contaminants there are,” she said. “Usually when you purify an element you’ll go through the cycle many times to reduce contaminants.”

With a higher separation factor, fewer steps and less solvents are needed, making the process faster and more cost-effective. For example, the scientists demonstrated for one of the three systems they purified that they could reduce the process from 25 steps to just two steps.

The Berkeley Lab researchers demonstrated their method first on actinium-225, an isotope of actinium that has shown very promising radio-therapeutic applications. It works by killing cancer cells but not healthy cells, through targeted delivery.

DOE’s Isotope Program is actively working on ramping up production of actinium-225 throughout the complex of national laboratory-based accelerators. This new separation method could be an alternative to chemical processes currently under development. “With any production process, you need to purify the final isotope,” Abergel said. “Our method could be used right after production, before distribution.”

The two other actinides purified in this study were plutonium and berkelium. An isotope of plutonium, plutonium-238, is used for power generation in robots being sent to explore Mars. Plutonium isotopes are also present in waste generated at nuclear power plants, where they must be separated out from the uranium in order to recycle the uranium.

Lastly, berkelium is important for fundamental science research. One of its uses is as a target for discovery of new elements.

The process relies on the unprecedented ability of synthetic ligands – small molecules that bind metal atoms – to be highly selective in binding to metallic cations (positive ions) based on the size and charge of the metal.

The next step, said Abergel, is to explore using the process on other medical isotopes. “Based on what we’ve seen, this new method can really be generalized, as long as we have different charges on the metals we want to separate,” she said. “Having a good purification process available could make everything easier in terms of post-production processing and availability.”

The study was funded by the DOE Office of Science. Ricano was previously a participant in DOE’s Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI) program at Berkeley Lab.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.

Media contact:

Laurel Kellner, [email protected], 510-590-8034