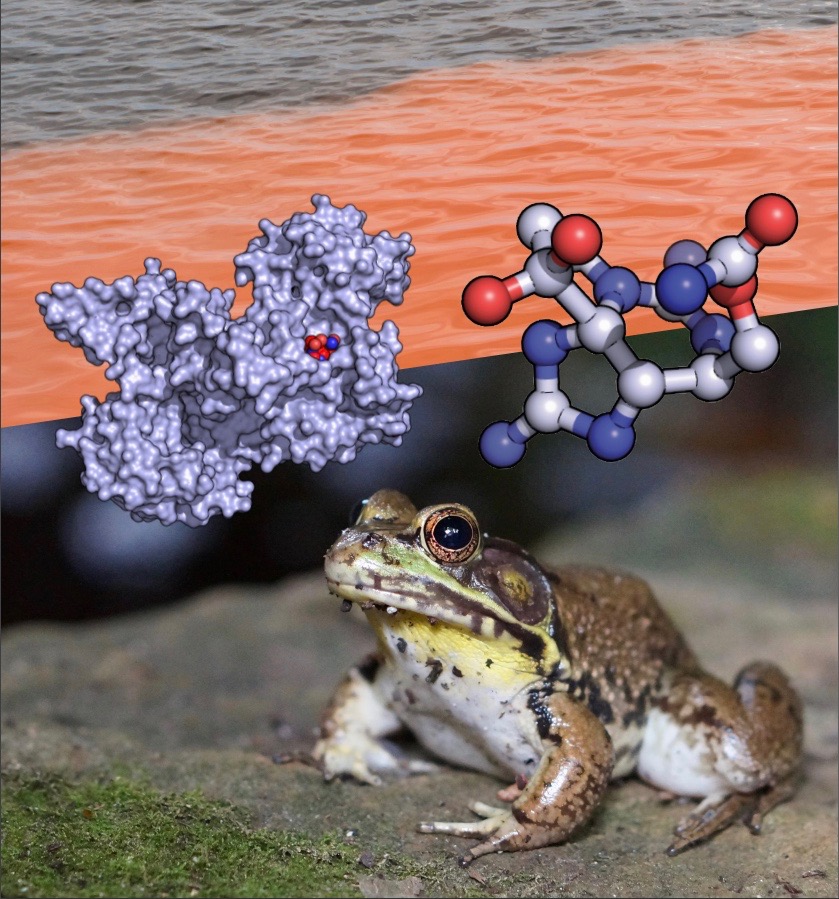

A photo illustration showing the atomic structures of saxiphilin and saxitoxin, a red tide algal bloom, and an American bullfrog (R. catesbeiana). (Credit: Daniel L. Minor, Jr., and Deborah Stalford/Berkeley Lab)

A team led by Berkeley Lab faculty biochemist Daniel Minor has discovered how a protein produced by bullfrogs binds to and inhibits the action of saxitoxin, the deadly neurotoxin made by cyanobacteria and dinoflagellates that causes paralytic shellfish poisoning.

The findings, published this week in Science Advances, could lead to the first-ever antidote for the compound, which blocks nerve signaling in animal muscles, causing death by asphyxiation when consumed in sufficient quantities.

“Saxitoxin is among the most lethal natural poisons and is the only marine toxin that has been declared a chemical weapon,” said Minor, who is also a professor at the UCSF Cardiovascular Research Institute. About one thousand times more potent than cyanide, saxitoxin accumulates in tissues and can therefore work its way up the food chain – from the shellfish that eat the microbes to fish, turtles, marine mammals, and us.

Minor and his colleagues elucidated the mechanism of the protective protein, called saxiphilin, by mapping the atomic structure of free saxiphilin and saxitoxin-bound saxiphilin using high-resolution X-ray crystallography performed at Berkeley Lab’s Advanced Light Source.

“Climate change is making blooms of toxic algae more common,” said Minor. “Understanding how frogs have developed molecules that help them to resist toxic environments holds important lessons that could help us have a defense at the ready. ”

To learn more about this research, read the full UCSF News Article.