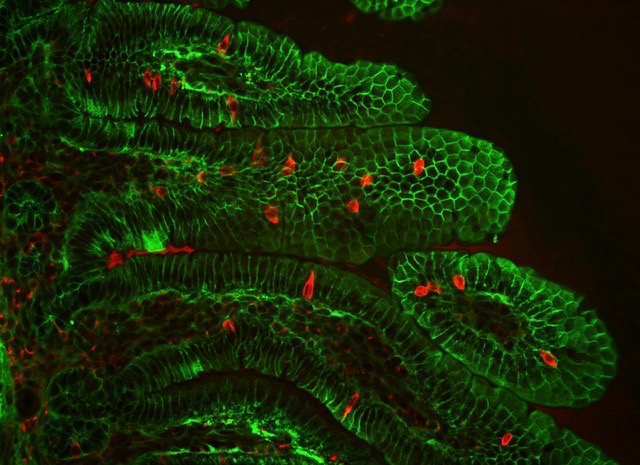

Detection of Percc1 expressing cells (red) amongst the epithelial cells (green) of the intestinal villi in a mouse. (Credit: Marco Osterwalder/Berkeley Lab)

Nearly 10 years ago, a group of Israeli clinical researchers emailed Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) geneticist Len Pennacchio to ask for his team’s help in solving the mystery of a rare inherited disease that caused extreme, and sometimes fatal, chronic diarrhea in children.

Now, following an arduous investigative odyssey that expanded our understanding of regulatory sequences in the human genome, the multinational scientific group has announced the discovery of the genetic explanation for this disease. Their findings are published in Nature.

“By identifying the underlying gene, we’ve opened the door for exploring therapeutic targets,” said Pennacchio, who has a dual appointment in Berkeley Lab’s Environmental Genomics and Systems Biology Division and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Joint Genome Institute. Although there are just a few families in the world known to carry the causative mutations, Pennacchio and his co-authors speculate that the condition, called intractable diarrhea of infancy syndrome (IDIS), may share disease-causing mechanisms with other gastrointestinal illnesses that affect millions of people – such as irritable bowel or Crohn’s disease. There are currently no treatments for IDIS other than nutritional and caloric support to make up for the impaired food absorption caused by frequent diarrhea. Typically, individuals with IDIS who survive infancy experience fewer symptoms as they get older, but their condition is never normal.

“The other important outcome is that the families now have an explanation for this disease, which has been afflicting children in the region for quite some time,” added Pennacchio.

Diving into a longstanding medical puzzle

Though it was first described in 1968, very little was known about IDIS before the clinical team’s lead researcher, Yair Anikster, began studying it in 2000. As it has only been identified in seven families of Iraqi-Jewish descent, the disease was simply too obscure to garner much attention from the medical science community. At the time, the only established information was that IDIS is a single-gene mediated recessive trait – meaning a child will show symptoms if they receive a mutated copy of the causative gene from both parents.

Researchers Len Pennacchio (top) and Yair Anikster. (Credit: Len Pennacchio and Sheba Medical Center)

Hoping to gain fresh insights into the illness through modern analytical techniques, Anikster and a diverse group of colleagues started by performing sequencing of all known gene sequences on samples they had collected from their IDIS patients.

Unfortunately, the results were far from clear-cut. All eight individuals did indeed carry mutations that are not found in healthy individuals from the same region, but these variations were found to be in apparently noncoding sequences – stretches of DNA that don’t get translated into a protein. More specifically, the patients (who represented each of the seven affected families) harbored deletions in both copies of a previously unstudied noncoding region on chromosome 16.

Noncoding sequences make up about 99% of the human genome and, despite their prevalence, are also the source of most unresolved questions about genetics. Once thought be to mere “junk’ DNA, scientists now know that some noncoding regions have important regulatory functions, yet digging deeper into the roles of these regions has always been much more challenging than studying DNA that codes for a protein.

Realizing they needed expert insight to establish a causal link between these deletions and IDIS, the group reached out to Pennacchio’s lab. An ideal fit for the challenge at hand, Pennacchio’s team has been examining genomic regulatory regions since completing the sequencing of chromosome 16 for the landmark Human Genome Project.

Finding a hidden gene

First, the geneticists used their world-leading mouse model platform to confirm that the chromosome 16 region is indeed a regulatory sequence involved in the development of the gastrointestinal system. When they engineered a lineage of mice with chromosomal deletions equivalent to those of Anikster’s human patients, the infant animals displayed diarrhea. These findings provided evidence that the noncoding sequence – which they termed the intestine-critical region (ICR) – is the cause of the disease. However, they still did not know what the regulatory sequence was actually regulating.

After years of painstaking experimentation, the authors were able to determine that the ICR controls expression of a previously unknown nearby gene, now called Percc1.

“It took years of gathering data from our mice before we uncovered that there was a gene very close to the deletion that we just happened to not be able to observe before,” said Pennacchio. He and his team found that Percc1 is present in all mammals and most vertebrates, thus establishing that it has been in animal genomes for eons. But because the protein this gene encodes is almost completely unlike any known proteins – in both sequence and structure – it was easily overlooked in gene mapping studies until the team started closely examining its chromosomal region.

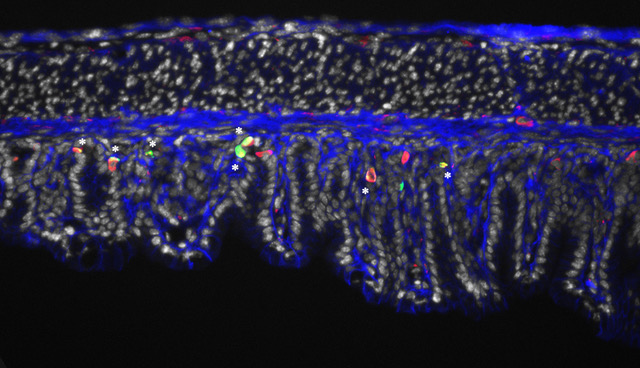

Identification of PERCC1 expressing cells (red) in the stomach epithelium (blue) of mice. Asterisks mark PERCC1 expressing cells with an endocrine identity (green). (Credit: Marco Osterwalder/Berkeley Lab)

Looking back at their human sequence data after this discovery, the authors saw that both types of ICR deletions carried in IDIS families prevent any Percc1 protein from being made. So, to formally connect the dots and prove that a lack of Percc1 gene expression is the sole cause of IDIS, they bred a new lineage of mice that had no genetic abnormalities other than a deleted Percc1 gene. Immediately after birth, the mutant mice experienced severe, chronic diarrhea that perfectly mirrored the disease progression of humans with IDIS. “That puts a nail in the coffin that yes, that must be what causes the condition because mice have the same exact symptoms,” explained Pennacchio.

Kicking off the next wave of research

After establishing what goes wrong when the enigmatic Percc1 protein is missing, the prolific scientists conducted one last round of experiments to provide a rough sketch of what it does under normal circumstances. Using their mouse model and human stem cells, the scientists showed that the Percc1 protein is expressed in (and necessary to the proper functioning of) a very small group of hormone-producing gastrointestinal cells. Through chemical signaling, these cells appear to mediate many processes, including intestinal motility, glucose uptake, and triggering the sense of satiety.

Moving forward, Anikster’s clinical teams at the Edmond and Lily Safra Children’s Hospital, the Sheba Medical Center, and the Sackler School of Medicine at Tel Aviv University plan to use their newfound knowledge of the gene to more closely study how the disease progresses over time. “The scientific journey was particularly long, challenging and full of surprises,” he said. “We hope that our discovery will pave the path towards targeted treatment of this potentially fatal disease.”

Meanwhile, Pennacchio’s lab will continue to do what they do best.

“For 20 years, we’ve been using the mouse as a powerful system to further understand not only the human genome, but also how all genomes function,” said Pennacchio. “Here at Berkeley Lab we’re focused on providing the tools and expertise needed to do the large-scale, complex work that smaller institutions can’t do on their own.”

The scientific supergroup behind this project come from 24 different institutions. The other authors are: Danit Oz-Levi, Tsviya Olender, Ifat Bar-Joseph, Yiwen Zhu*, Dina Marek-Yagel, Iros Barozzi*, Marco Osterwalder*, Anna Alkelai, Elizabeth Ruzzo, Yujun Han, Erica Vos, Haike Reznik-Wolf, Corina Hartman, Raanan Shamir, Batia Weiss, Rivka Shapiro, Ben Pode-Shakked, Pavlo Tatarskyy, Roni Milgrom, Michael Schvimer, Iris Barshack, Denise Imai, Devin Coleman-Derr, Diane Dickel*, Alex Nord*, Veena Afzal*, Kelly Lammerts van Bueren, Ralston Barnes, Brian Black, Christopher Mayhew, Matthew Kuhar, Amy Pitstick, Mehmet Tekman, Horia Stanescu, James Wells, Robert Kleta, Wouter de Laat, David Goldstein, Elon Pras, Axel Visel*, and Doron Lancet. (* Authors from Berkeley Lab.)

The Pennacchio lab’s contribution to this study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. This study was supported by the Wolfson Family Charitable Trust and the Crown Human Genome Center at the Weizmann Institute of Science; the SysKid EU FP7 project; the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; the National Human Genome Research Institute; and the Cincinnati Children’s – Sheba Medical Center’s Joint Research Fund.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.