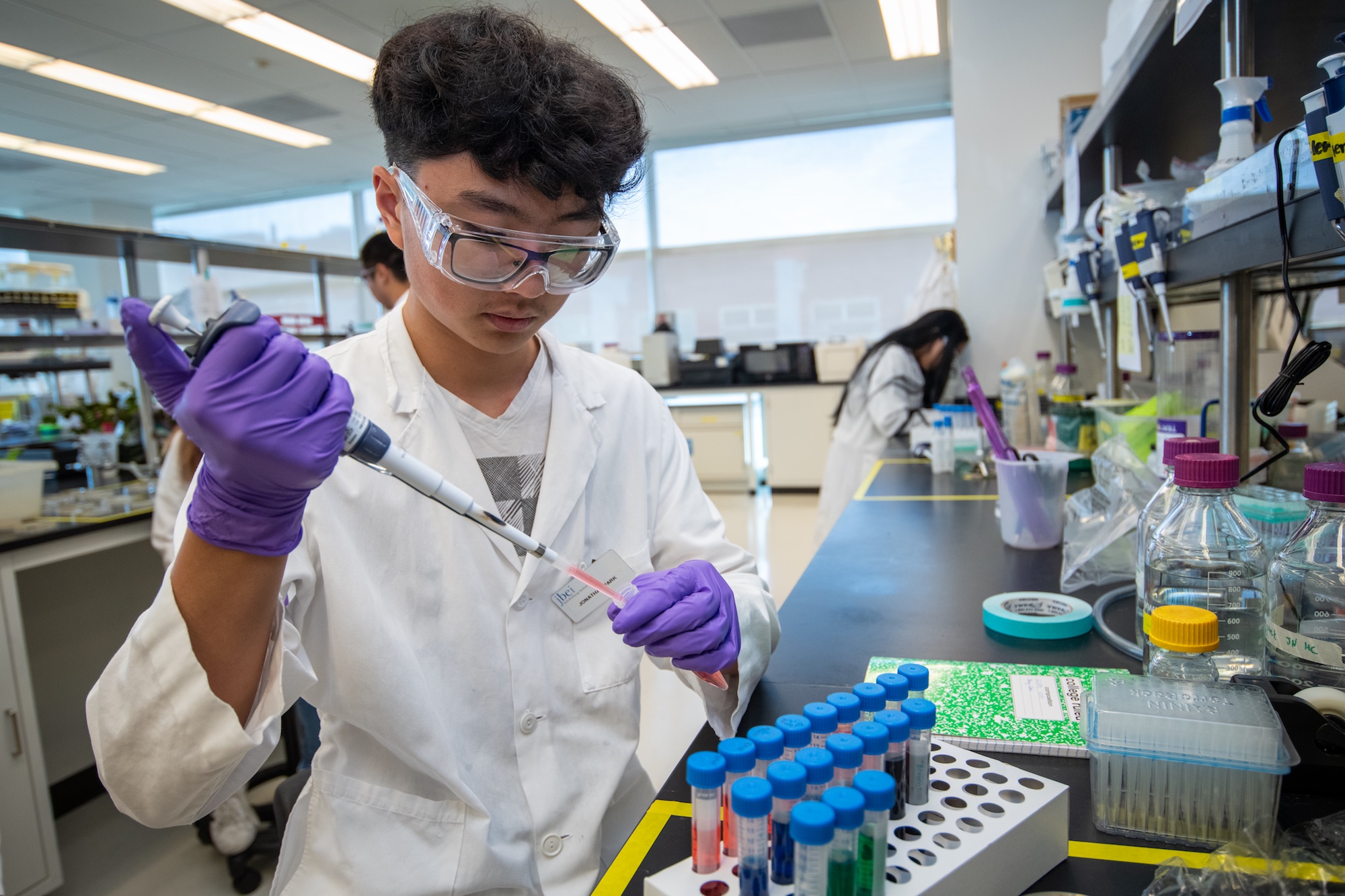

It’s 1 p.m. on a sunny afternoon in July – smack dab in the middle of summer break – and a perfect 75 degrees outside; but Jonathan Park is laser-focused. Though he could be strolling down a beach, or at home browsing social media, this 16-year-old is bent over a lab bench, intently pipetting reagents to run an Amplex Red Assay.

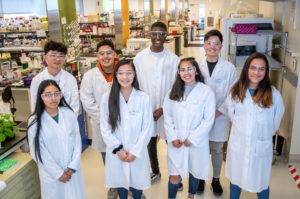

Park, a soon-to-be junior at Dublin High School, is part of the 2019 cohort of the Introductory College Level Experience in Microbiology (iCLEM) summer intensive, hosted and run by the Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI) in Emeryville. First launched in 2008, iCLEM immerses local Bay Area students in the biological sciences – and gives them a taste of day-to-day life as a scientist – through an eight-week-long blended curriculum of instruction, hands-on basic laboratory skill training, and in-depth tours of working labs within JBEI, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (which manages JBEI), and local biotech companies. The students, who receive a stipend so that they may attend the program in place of a summer job, utilize their newfound knowledge by conducting independent research projects and presenting their findings at the end of the program.

“I didn’t really know what to expect, I thought maybe we would just come in and do some experiments here and there,” said Park, while on a break from the lab. He explained that he hadn’t been drawn to science until last year’s honors chemistry class challenged him in a way that got his attention. “I was like, okay, this is really interesting, I need to try this out. And iCLEM was there at just the right time. Being here has really shattered my idea of biology, chemistry and physics being these separate things – I’ve learned that they’re all just an integrated science that researchers use to do all these cool things, like making biofuels and actually saving the environment.”

The experience at iCLEM has motivated Park, who previously planned to study music, to pursue a double major with biochemistry when he attends college in 2021. If he follows through with his ambitions, Park will be in good company. According to Lauchlin Cruickshanks, iCLEM’s educational program administrator, 95% of past participants have gone on to continue their education at two or four-year colleges and universities, and 80% majored in science or engineering. Given that the program specifically recruits teens who face socioeconomic hurdles to higher education, this impressive attendance rate is a point of pride among the scientists and educators who make iCLEM happen.

Hoping to spread their prodigiously successful model beyond the confines of JBEI, a group of former and current scientific advisors have shared the iCLEM curriculum in the Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education.

“There are so many different curricula to teach basic microbiology and biochemistry already in journals, but I think one of the attractive things about this approach, and the reason it resonates with kids, is that we talk about science through the lens of sustainability,” said Jesus Barajas, the first author of the paper and a former scientific advisor for iCLEM. “Our overall goal is to teach these concepts by having students learn how to produce biofuels and bioproducts in a sustainable fashion. This is more meaningful, because if we want to think of them as the next generation of scientists, we don’t just want to train them to tackle the problems of today and tomorrow, but also for them to really understand the problems.”

From the outset, iCLEM has been dedicated to nurturing budding scientists who would not otherwise have access to a college preparation scientific internship. Nearly all students are from low-income families, and many are also English language learners and/or the first generation to attend college. Clem Fortman and James Carothers, the program’s founders, came up with the premise for iCLEM during a conversation about what was lacking in STEM education. At the time, they were both postdoctoral researchers at JBEI and the Synthetic Biology Research Center (Synberc), a collaborating institution located in the same building.

“We talked about how a lot of the existing programs acted as a leg up for folks who already had a leg up. And it turned out that James and I shared the experience of having to work summers and weekends when we were teenagers,” said Fortman, who served as iCLEM’s scientific director for the first four years and is currently director of operations for the lab of Jay Keasling, JBEI’s CEO. “We didn’t have the resources or opportunities to go into the types of school camps and other stuff that can help get kids onto the STEM career track – something that is still the reality of life for many people, especially in the Bay Area.”

As the duo continued discussing the unmet needs in science education, Fortman excitedly realized that much of the fundamental laboratory work supporting JBEI and Synberc’s biofuels research, i.e., the tasks typically done by undergraduate students, could be used as a real-world foundation for teaching basic microbiology and biochemistry. With that conversation, the concept for iCLEM was born. Fortman and Carothers soon pitched their idea to Keasling, drawing upon their own career journeys as they emphasized that providing “opportunities to those who don’t have an easy pipeline into science” means small class sizes, providing financial assistance, and offering college preparation support. Their proposal was approved on the spot.

“I had some really high expectations for iCLEM and [it has] surpassed them all. I love this program. It’s the highlight of my summer,” said participant Zoe Siman-Tov. “The things we got to do are things that you’d never be able to get to do in high school. And being able to do it myself has really cemented it in, and I’m very sure that I’d like to work in a lab.”

Over the next several years, iCLEM’s curriculum evolved organically, as the founding scientists and a rotating roster of advisors, enthusiastic mentors, and high-school teachers – who help lead the instruction-based portions of the program – refined and enriched their approach.

Raymundo Sanchez, a past student in the 2015 cohort, notes that iCLEM’s behind-the-scenes instructional model helped guide him toward his current interest in biological anthropology. He will soon begin his senior year at UC Santa Barbara as a double-major in the field, alongside Chicano/a studies. “I really love my majors and feel like they blend perfectly what I strive to do in the future, which is help out underrepresented communities by helping them gain better access to healthcare and education,” said Sanchez. “But I would have not even thought of all the different careers that are possible within STEM if it wasn’t for my internships, which were hard to find and only a handful of them were out there for underrepresented individuals. For STEM fields to become more diverse, I think it would be helpful to have more experiences, like iCLEM, that bring awareness and exposure to the many possibilities out there.”

Now that the details of iCLEM are widely available, Fortman and the rest of the team are optimistic that other programs with the same core tenets will indeed develop, and that more teens than could ever fit at the JBEI lab benches will soon be able to participate.

Looking back, the group regards the many hours of volunteered time spent developing the curriculum and building iCLEM into the experience it is today as a necessary contribution toward the long-overdue, large-scale shift that is happening throughout the education framework. “I believe that the STEM fields are trying to be more inclusive than they were,” said Fortman. “But there needs to be educational equality much earlier than when we’re intervening, starting at day one.”

iCLEM is currently funded by JBEI, which is supported by the DOE Office of Science; the Amgen Foundation, administered through UC Berkeley; and the Heising-Simons Fund.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.