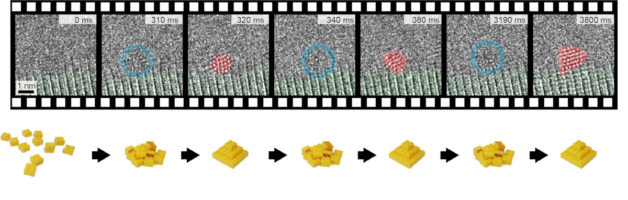

Berkeley Lab scientists and collaborators took advantage of one of the best microscopes in the world – the TEAM I electron microscope at the Molecular Foundry – to watch how individual gold atoms organized themselves into crystals on top of graphene. The research team observed as groups of gold atoms formed and broke apart many times, trying out different configurations, before finally stabilizing. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

When we grow crystals, atoms first group together into small clusters – a process called nucleation. But understanding exactly how such atomic ordering emerges from the chaos of randomly moving atoms has long eluded scientists.

Classical nucleation theory suggests that crystals form one atom at a time, steadily increasing the level of order. Modern studies have also observed a two-step nucleation process, where a temporary, high-energy structure forms first, which then changes into a stable crystal. But according to an international research team co-led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), the real story is even more complicated.

Their findings, recently reported in the journal Science, reveal that rather than grouping together one-by-one or making a single irreversible transition, gold atoms will instead self-organize, fall apart, regroup, and then reorganize many times before establishing a stable, ordered crystal. Using an advanced electron microscope, the researchers witnessed this rapid, reversible nucleation process for the first time. Their work provides tangible insights into the early stages of many growth processes such as thin-film deposition and nanoparticle formation.

Animation of the new paradigm in crystal formation, visualized with Lego bricks: a dynamically fluctuating nucleation process. (Credit: Won Chul Lee/Hanyang University)

“As scientists seek to control matter at smaller length scales to produce new materials and devices, this study helps us understand exactly how some crystals form,” said Peter Ercius, one of the study’s lead authors and a staff scientist at Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry.

In line with scientists’ conventional understanding, once the crystals in the study reached a certain size, they no longer returned to the disordered, unstable state. Won Chul Lee, one of the professors guiding the project, describes it this way: if we imagine each atom as a Lego brick, then instead of building a house one brick at a time, it turns out that the bricks repeatedly fit together and break apart again until they are finally strong enough to stay together. Once the foundation is set, however, more bricks can be added without disrupting the overall structure.

Stills from a slow-motion video of the reversible Au crystal formation process on the atomic scale. (Credit: Berkeley Lab)

The unstable structures were only visible because of the speed of newly developed detectors on the TEAM I, one of the world’s most powerful electron microscopes. A team of in-house experts guided the experiments at the National Center for Electron Microscopy in Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry. Using the TEAM I microscope, researchers captured real-time, atomic-resolution images at speeds up to 625 frames per second, which is exceptionally fast for electron microcopy and about 100 times faster than previous studies. The researchers observed individual gold atoms as they formed into crystals, broke apart into individual atoms, and then reformed again and again into different crystal configurations before finally stabilizing.

“Slower observations would miss this very fast, reversible process and just see a blur instead of the transitions, which explains why this nucleation behavior has never been seen before,” said Ercius.

The reason behind this reversible phenomenon is that crystal formation is an exothermic process – that is, it releases energy. In fact, the very energy released when atoms attach to the tiny nuclei can raise the local “temperature” and melt the crystal. In this way, the initial crystal formation process works against itself, fluctuating between order and disorder many times before building a nucleus that is stable enough to withstand the heat. The research team validated this interpretation of their experimental observations by performing calculations of binding reactions between a hypothetical gold atom and a nanocrystal.

Now, scientists are developing even faster detectors which could be used to image the process at higher speeds. This could help them understand if there are more features of nucleation hidden in the atomic chaos. The team is also hoping to spot similar transitions in different atomic systems to determine whether this discovery reflects a general process of nucleation.

One of the study’s lead authors, Jungwon Park, summarized the work: “From a scientific point of view, we discovered a new principle of crystal nucleation process, and we proved it experimentally.”

The research collaboration was led by Berkeley Lab in collaboration with South Korea’s Hanyang University, Seoul National University, and Institute for Basic Science.

The Molecular Foundry is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

This work was mainly supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea. Work at the Molecular Foundry was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Additional funding was provided by the Institute for Basic Science (Korea), Samsung Science and Technology Foundation, and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 13 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.