What does the European Climate Exchange in London have to do with the rural Yaya Gulelle district in Ethiopia?

Everything—if all goes well in some test chambers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory this summer.

Ethiopia has experienced severe deforestation in the last century. Its natural forest cover has plummeted from 35 percent at the start of the 20th century to just 3 percent today. While agricultural practices, including coffee production, are one of the main causes, collecting wood for cooking fuel is also a major contributing factor. About 80 percent of the population still uses traditional three-stone fires to prepare meals, a highly inefficient and polluting method of cooking. The average household uses 11 kg of wood-equivalent per day, or 4 metric tons annually, according to World Vision. And Ethiopia is hardly unique in this regard: according to the Partnership for Clean Indoor Air, more than half the world’s population—or about 3 billion people—cooks with open fires or rudimentary stoves.

Imagine if these traditional stoves could be swapped out for more energy-efficient ones that used less wood: how much in carbon dioxide emissions could be offset? Berkeley Lab researchers, led by senior scientist Ashok Gadgil, have already designed an efficient cookstove specifically for women living in makeshift camps for displaced persons in Darfur. Each Berkeley-Darfur Stove, which uses two to three times less wood than traditional stoves, prevents up to two tons of carbon dioxide emissions annually. It also reduces the amount of time these women need to spend foraging for firewood, thus limiting their exposure to violence and assaults. Thousands of the stoves are being distributed this year through the Darfur Stove Project’s partnership with Oxfam America and the Sustainable Action Group, a Sudanese organization.

In light of these achievements, the non-profit World Vision approached Berkeley Lab to modify its Darfur stove for Ethiopia. However, instead of financing the scale-up of stove dissemination through charities, World Vision intends for the pilot project to have a self-sustaining scale-up by taking advantage of the world carbon market. Given that each stove has a lifetime of about five years, and that one ton of carbon sells for about $14 on the carbon exchange in Europe, a stove that costs less than $25 to produce can generate $140 in income.

“It’s an innovative way to fund what has traditionally been seen as a humanitarian project,” says Gadgil. “In fact, efficient cookstoves benefit the people using them by reducing their labor to collect fuelwood, improving their indoor air quality, and reducing the attendant adverse health impacts of exposure to smoke while helping to save their forests. In addition, the world also benefits because there’s less carbon dioxide emitted. If we want to reduce CO2, it’s better to go where it’s cheapest to do that.”

Of course, a large number of stoves would have to be installed to cover the substantial up-front investment for setting up the certification, monitoring process and the legal paperwork to enter into carbon trading in Europe. But with an enormous prospective market in dozens of underdeveloped countries, basic cookstoves, once funded only by government grants and humanitarian organizations, have become an attractive business investment with a large potential payoff.

Modifying the Stove for Ethiopia: Coffee and Ash Pans

For the Berkeley Lab scientists, not all cookstoves are the same. Maximizing efficiency requires understanding what kind of food, fuels, utensils and pots are used. With funding from the U.S. Department of Energy, Gadgil and UC Berkeley doctoral student Kayje Booker travelled to the Yaya Gulelle district about 70 miles north of Addis Adaba last year to observe women cooking.

They found some critical differences with the cooking process in Darfur. Not only was the food different, but also Ethiopian women sometimes use cow dung as a fuel, which produces more smoke than wood does. Their pots were also far more varied in size and shape than in Darfur; plus, Ethiopian women make coffee several times a day—both brewing and roasting the beans—requiring supports in the stove to accommodate coffee pots and roasting pans. Besides observing the cooking practices and informally interviewing several local people, the Berkeley team also purchased a full set of Ethiopian cooking pots to bring back to Berkeley.

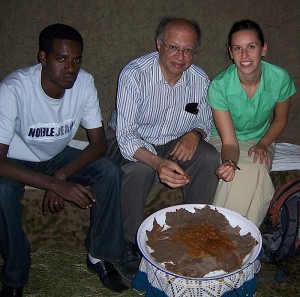

Ashok Gadgil (center) and Kayje Booker sample the lentil stew on injera bread cooked on a traditional Ethiopian stove. (Photo courtesy Kayje Booker)

With those pots in hand and armed with the information on cooking conditions, the Berkeley Lab scientists modified the pot supports and handles of the Berkeley-Darfur Stove and made a second trip in January, bringing three different prototypes with them for women to evaluate. On that trip, they made another important discovery: that households in Ethiopia take pride in their clean bare-earth floors—what a Westerner might call a “dirt floor.”

“For a Westerner, it was never in our mind to worry about getting their dirt floors dirty,” says Adam Rausch, a graduate student in civil environmental engineering who traveled to Ethiopia in January. But in fact, one woman became rather agitated when the ash from a test stove created a small mess in her house.

Because the stove for Darfur is used almost exclusively outdoors or in the same indoor space as a three-stone fire, keeping the ash from the firewood away from the floor was not ever an objective. Added Jessica Granderson, who directs the stove testing at Berkeley Lab and accompanied Rausch on the Ethiopia trip: “Let it be known, that same night, we were banging out an ash pan from spare sheet metal parts.”

Back at Berkeley Lab, stove designers gathered all the feedback and came up with a pilot design. A factory in India has built 20 stoves per this design, complete with ash pans, which will be shipped to Ethiopia for more extended testing by World Vision. The goal is to distribute another 1,000 for a second round of testing in the fall if the tests results from the first 20 are acceptable.

The Water Boiling Test

Meanwhile, Berkeley Lab scientists continue to conduct testing on the Berkeley-Ethiopia stove, measuring the rate of fuel burning and indoor emission levels. They have just concluded the water boiling test, a general test that is useful for comparing different stoves and cooking methods, though it will not necessarily provide emission levels for a specific type of food. The test involves heating the stoves from a cold start and a hot start, each time bringing 5 liters of water to a boil then holding it on simmer for 45 minutes. The Berkeley Lab scientists compared their results to results obtained by World Vision from performing the same test with an open fire and with three other fuel-efficient stoves being considered for dissemination in Ethiopia.

“In a nutshell, our stoves are slower but more efficient than the other stoves. That is, it may take a bit longer to boil equivalent amounts of water, but we will use less wood doing so,” says Rausch.

Testing will continue through the summer in Ethiopia under supervision of World Vision in what is called a “controlled cooking test,” which more closely simulates the cooking cycle in an Ethiopian meal, emulating the actual food cooked: lentils, onions, beans and stew.

An Expanded Role in Cookstoves

Meanwhile, Gadgil and his team have received requests to modify their stove for Haiti, where much of the population has been displaced due to the recent earthquake. But a trip to Haiti found that many groups were already trying to distribute numerous different designs of fuel-efficient stoves. “If there are 20 NGOs [nongovernmental groups] with 20 models of stoves, what is the value we can add?” says Gadgil. “It’s not to design the twenty-first stove.”

It was decided that the most useful role Berkeley Lab could play is to perform benchmarking of the large variety of cookstoves available and become a clearinghouse of information for the Haiti stoves effort. Although a number of scientists and nonprofit organizations are working on fuel-efficient cookstoves for Haiti, no generally accepted test protocols and reliable and credible test results exist for comparing the fuel-efficiency of one stove versus another.

“Several NGOs have sent us stoves to test and enthusiastically written to thank us for performing this service, so we hope to develop it further,” says Gadgil. “What started as the stoves work first for Darfur, and then for Ethiopia, is now acting as a bridge between scientists and NGOs in Haiti with boots on the ground.”

Berkeley Lab is a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national laboratory located in Berkeley, California. It conducts unclassified scientific research and is managed by the University of California for the DOE Office of Science. Visit our website at http://www.lbl.gov.

Additional Information:

- Darfur Stoves Project

- Slideshow of workers being trained to assemble stoves in Darfur

- Blum Center for Developing Economies, a major supporter of the Berkeley-Darfur Stove