Looking strictly at the economic costs and benefits of three different roof types—black, white and “green” (or vegetated)—Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) researchers have found in a new study that white roofs are the most cost-effective over a 50-year time span. While the high installation cost of green roofs sets them back in economic terms, their environmental and amenity benefits may at least partially mitigate their financial burden.

A new report titled “Economic Comparison of White, Green, and Black Flat Roofs in the United States” by Julian Sproul, Benjamin Mandel, and Arthur Rosenfeld of Berkeley Lab, and Man Pun Wan of Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, provides a direct economic comparison of these three roof types. The study will appear in the March 2014 volume of Energy and Buildings and has just been published online. “White roofs win based on the purely economic factors we included, and black roofs should be phased out,” said study co-author Rosenfeld, a Berkeley Lab Distinguished Scientist Emeritus and former Commissioner of the California Energy Commission.

The study analyzes 22 commercial flat roof projects in the United States in which two or more roof types were considered. The researchers conducted a 50-year life cycle cost analysis, assuming a 20-year service life for white and black roofs and a 40-year service life for green roofs.

The study analyzes 22 commercial flat roof projects in the United States in which two or more roof types were considered. The researchers conducted a 50-year life cycle cost analysis, assuming a 20-year service life for white and black roofs and a 40-year service life for green roofs.

A green roof, often called vegetated roofs or rooftop gardens, has become an increasingly popular choice for aesthetic and environmental reasons. Rosenfeld acknowledges that their economic analysis does not capture all of the benefits of a green roof. For example rooftop gardens provide stormwater management, an appreciable benefit in cities with sewage overflow issues, while helping to cool the roof’s surface as well as the air. Green roofs may also give building occupants the opportunity to enjoy green space where they live or work.

“We leave open the possibility that other factors may make green roofs more attractive or more beneficial options in certain scenarios,” said Mandel, a graduate student researcher at Berkeley Lab. “The relative costs and benefits do vary by circumstance.”

However, unlike white roofs, green roofs do not offset climate change. White roofs are more reflective than green roofs, reflecting roughly three times more sunlight back into the atmosphere and therefore absorbing less sunlight at earth’s surface. By absorbing less sunlight than either green or black roofs, white roofs offset a portion of the warming effect from greenhouse gas emissions.

“Both white and green roofs do a good job at cooling the building and cooling the air in the city, but white roofs are three times more effective at countering climate change than green roofs,” said Rosenfeld.

White roofs are most cost-effective

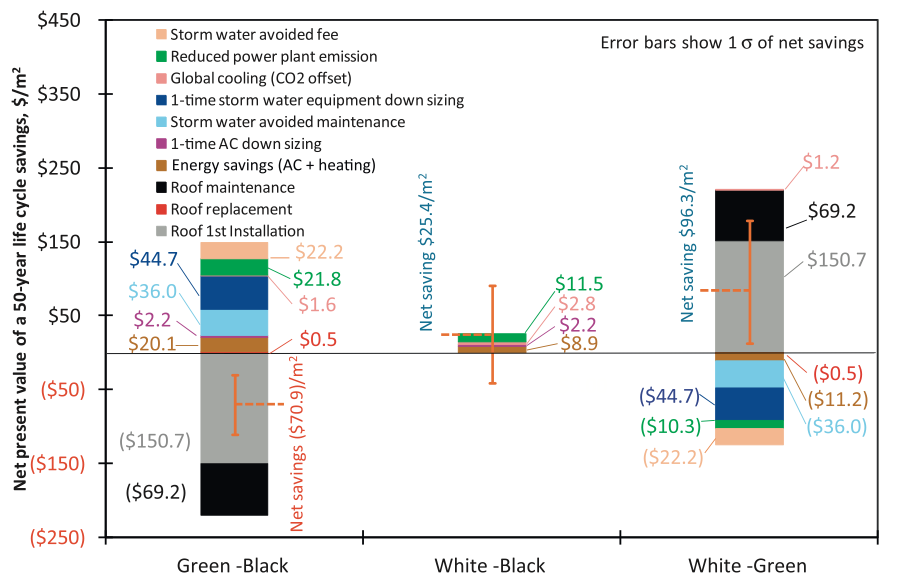

The costs and benefits difference stack that has the highest net present value shows the roof type that is most cost-effective. Parentheses around dollar values indicate negative values. (Click for larger image.)

The 50-year life-cycle cost analysis found that even the most inexpensive kind of green roof (with no public access and consisting of only sedum, or prairie grass) costs $7 per square foot more than black roofs over 50 years, while white roofs save $2 per square foot compared to black roofs. In other words, white roofs cost $9 per square foot less than green roofs over 50 years, or $0.30 per square foot each year.

The researchers acknowledge that their data are somewhat sparse but contend that their analysis is valuable in that it is the first to compare the economic costs and energy savings benefits of all three roof types. “When we started the study it wasn’t obvious that white roofs would still be more cost-effective over the long run, taking into account the longer service time of a green roof,” Mandel said.

Furthermore while the economic results are interesting, it also highlights the need to include factors such health and environment in a more comprehensive analysis. “We’ve recognized the limitations of an analysis that’s only economic,” Mandel said. “We would want to include these other factors in any future study.”

Black roofs pose health risk

For example, black roofs pose a major health risk in cities that see high temperatures in the summer. “In Chicago’s July 1995 heat wave a major risk factor in mortality was living on the top floor of a building with a black roof,” Rosenfeld said.

For that reason, he believes this latest study points out the importance of government policymaking. “White doesn’t win out over black by that much in economic terms, so government has a role to ban or phase out the use of black or dark roofs, at least in warm climates, because they pose a large negative health risk,” he said.

Rosenfeld, who started at Berkeley Lab in the 1950s, is often called California’s godfather of energy efficiency for his pioneering work in the area. He was awarded a National Medal of Technology and Innovation by President Obama in 2012, one of the nation’s highest honors.

Rosenfeld has been a supporter of solar-reflective “cool” roofs, including white roofs, as a way to reduce energy costs and address global warming. He was the co-author of a 2009 study in which it was estimated that making roofs and pavements around the world more reflective could offset 44 billion tons of CO2 emissions. A later study using a global land surface model found similar results: cool roofs could offset the emissions of roughly 300 million cars for 20 years.

Cool roofs have been proliferating. They are used in about two-thirds of new roof or re-roof installations in the western U.S. In California they have been part of prescriptive requirements of the Title 24 Building Energy Efficiency Standards since 2005 for all new nonresidential, flat roof buildings (including alterations and additions).

# # #

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.