Lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide, or NMC, is one of the most promising chemistries for better lithium batteries, especially for electric vehicle applications, but scientists have been struggling to get higher capacity out of them. Now researchers at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have found that using a different method to make the material can offer substantial improvements.

Working with scientists at two other Department of Energy (DOE) labs—Brookhaven National Laboratory and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory—a team led by Berkeley Lab battery scientist Marca Doeff was surprised to find that using a simple technique called spray pyrolysis can help to overcome one of the biggest problems associated with NMC cathodes—surface reactivity, which leads to material degradation.

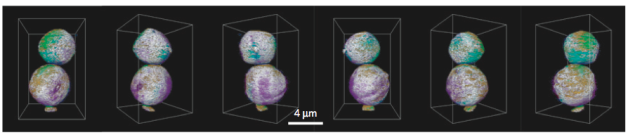

These 3D elemental association maps generated using transmission X-ray tomography show the cathode material made by Berkeley Lab Marca Doeff and her team using spray pyrolysis.

“We made some regular material using this technique, and lo and behold, it performed better than expected,” said Doeff, who has been studying NMC cathodes for about seven years. “We were at a loss to explain this, and none of our conventional material characterization techniques told us what was going on, so we went to SLAC and Brookhaven to use more advanced imaging techniques and found that there was less nickel on the particle surfaces, which is what led to the improvement. High nickel content is associated with greater surface reactivity.”

Their results were published online in the premier issue of the journal Nature Energy in an article titled, “Metal segregation in hierarchically structured cathode materials for high-energy lithium batteries.” The facilities used were the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at SLAC and the Center for Functional Nanomaterials (CFN) at Brookhaven, both DOE Office of Science User Facilities.

These results are potentially significant because they pave the way for making lithium-ion batteries that are cheaper and have higher energy density. “We still want to increase the nickel content even further, and this gives us a possible avenue for doing that,” Doeff said. “The nickel is the main electro-active component, plus it’s less expensive than cobalt. The more nickel you have, the more practical capacity you may have at voltages that are practical to use. We want more nickel, but at the same time, there’s the problem with surface reactivity.”

The cathode is the positive electrode in a battery, and development of an improved cathode material is considered essential to achieving a stable high-voltage cell, the subject of intense research. Spray pyrolysis is a commercially available technique used for making thin films and powders but has not been widely used to make materials for battery production.

The surface reactivity is a particular problem for high-voltage cycling, which is necessary to achieve higher capacities needed for high-energy devices. The phenomenon has been studied and various strategies have been tried to ameliorate the issue over the years, including using partial titanium substitution for cobalt, which counteracts the reactivity of the surfaces to some extent.

At SSRL researchers Dennis Nordlund and Yijin Liu used x-ray transmission microscopy and spectroscopy to examine the material in the tens of nanometers to 10-30 micron range. At CFN researcher Huolin Xin used a technique called electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) with a scanning transmission electron microscope (STEM), which was able to zoom in on details down to the nanoscale.

At these two scales, Doeff and her Berkeley Lab colleagues—Feng Lin, Yuyi Li, Matthew Quan, and Lei Cheng—working with the scientists at SSRL and CFN made some important findings about the material.

Lin, a former Berkeley Lab postdoctoral researcher working with Doeff and first author on the paper, said: “Our previous studies revealed that engineering the surface of cathode particles could be the key to stabilizing battery performance. After some deep effort to understand the stability challenges of NMC cathodes, we are now getting one step closer to improving NMC cathodes by tuning surface metal distribution.”

The research results point the way to further refinements. “This research suggests a path forward to getting these materials to cycle with higher capacities—that is to design materials that are graded, with less nickel on the surface,” Doeff said. “I think our next step will be to try to make these materials with a larger compositional gradient and combine some other things to make them work together, such as titanium substitution, so we can utilize more capacity and thereby increase the energy density in a lithium ion battery.”

Spray pyrolysis is an inexpensive, common technique for making materials. “The reason we like it is that it offers a lot of control over the morphology. You get beautiful spherical morphology which is very good for battery materials,” Doeff said. “We’re not the first ones who have come up with idea of decreasing nickel on the surface. But we were able to do it in one step using a very simple procedure.”

This research was supported by DOE’s Vehicle Technologies Office.

# # #

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory addresses the world’s most urgent scientific challenges by advancing sustainable energy, protecting human health, creating new materials, and revealing the origin and fate of the universe. Founded in 1931, Berkeley Lab’s scientific expertise has been recognized with 13 Nobel prizes. The University of California manages Berkeley Lab for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science. For more, visit www.lbl.gov.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit science.energy.gov.