Since buildings consume 75% of electricity in the U.S., they offer great potential for saving energy and reducing the demands on our rapidly changing electric grid. But how much, where, and through which strategies could better management of building energy use actually impact the electricity system?

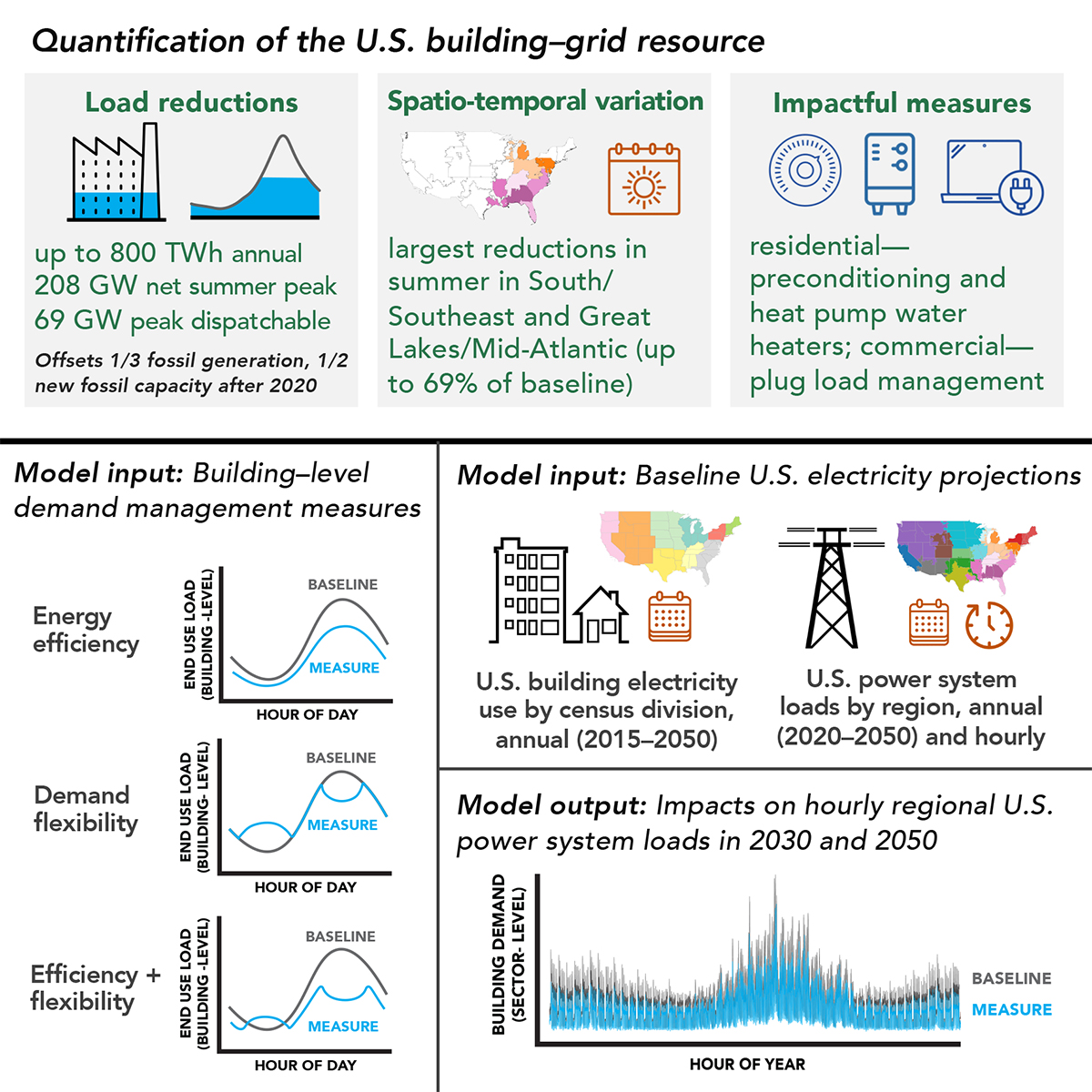

A comprehensive new study led by researchers from the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) answers these questions, quantifying what can be done to make buildings more energy efficient and flexible in granular detail by both time (including time of day and year) and space (looking at regions across the U.S.). The research team, which also included scientists from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), found that maximizing the deployment of building demand management technologies could avoid the need for up to one-third of coal- or gas-fired power generation and would mean that at least half of all such power plants that are expected to be brought online between now and 2050 would not need to be built.

Their findings were published recently in the journal Joule.

“A key reason why we don’t hear more about the role of our buildings as a significant resource for the clean energy transition is because it’s been challenging to quantify that resource at a large scale – and without hard numbers at scale, it’s hard for policy makers or grid operators to plan around it,” said Berkeley Lab researcher Jared Langevin, lead author of the study. “Our overarching belief here was that producing these kinds of estimates that make the role of these demand-side building technologies more concrete will help ensure that we do more to encourage the deployment of those technologies alongside the deployment of renewable generation and batteries.”

“We’re excited to collaborate with Berkeley Lab on these research findings, which emphasize the impact of our nation’s buildings to achieve a decarbonized energy system,” said Achilles Karagiozis, director of NREL’s Building Technologies and Science Center.

The so-called demand-side of electricity is electricity that is used in homes and workplaces, such as for air conditioning, water heating, and powering lights and appliances. The researchers approached this electricity use from buildings as a grid resource; by increasing the efficiency and flexibility of buildings’ electricity use, such as by operating higher-performing equipment and shifting the time when its usage takes place, they found this resource to be substantial, avoiding up to 742 terawatt-hours (TWh) of annual electricity use and 181 gigawatts (GW) of daily net peak load in 2030, rising to 800 TWh and 208 GW by 2050. (Total U.S. electricity consumption in 2020 was about 3,800 TWh.)

The researchers found that the most impactful measures for residential buildings were preconditioning (where homes are precooled so as to reduce air-conditioning usage at peak times) and using heat pump water heaters; for commercial buildings, plug load management, where software is used to manage the electricity use of computers and other electronic devices in a building, was most impactful.

“Our initial estimates suggest tens of billions of dollars in annual cost savings potential for grid operators – not to mention the potential energy cost savings for families and businesses,” said Karagiozis. “Buildings are also a significant source of flexibility for grid operators, primarily in dialing down electricity demand during times when it would normally be at its peak, such as during really hot summer days when most air conditioners are running.”

By reducing this peak demand, Langevin said utilities may have lower need for battery technologies as they deploy more renewable energy. “Indeed, the flexible resource we found is comparable to higher-end projections of battery deployment needs under higher renewable energy deployment,” he said.

The regions where buildings proved to offer the largest grid resource were in Texas and the Southeast of the U.S., as well as the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions. “These are areas with high population, strong space conditioning needs, and lots of electric equipment already installed,” Langevin said. “This information at the regional scale is really important for developing tangible policies for realizing the resource that we’re reporting.”

Strategies for capturing the potential building-grid resource that the study identifies are already under development. Recently, for example, DOE released a National Roadmap for Grid-Interactive Efficient Buildings, which draws from the study’s outcomes and provides concrete recommendations for how to triple the efficiency and flexibility of the buildings sector by 2030.

“Continued efforts along these lines will be critical for establishing a key role for the buildings sector in the future evolution of the U.S. electricity system,” said Langevin. “Our findings are encouraging, but now we need to find ways of quickly putting this resource into practice.”

The study was supported by the Building Technologies Office under DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 14 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.