Anything made out of plastic or glass is known as an amorphous material. Unlike many materials that freeze into crystalline solids, the atoms and molecules in amorphous materials never stack together to form crystals when cooled. In fact, although we commonly think of plastic and glass as “solids,” they instead remain in a state that is more accurately described as a supercooled liquid that flows extremely slowly. And although these “glassy dynamic” materials are ubiquitous in our daily lives, how they become rigid at the microscopic scale has long eluded scientists.

Now, researchers at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) have discovered molecular behavior in supercooled liquids that represents a hidden phase transition between a liquid and a solid.

Their improved understanding applies to ordinary materials like plastics and glass, and could help scientists develop new amorphous materials for use in medical devices, drug delivery, and additive manufacturing.

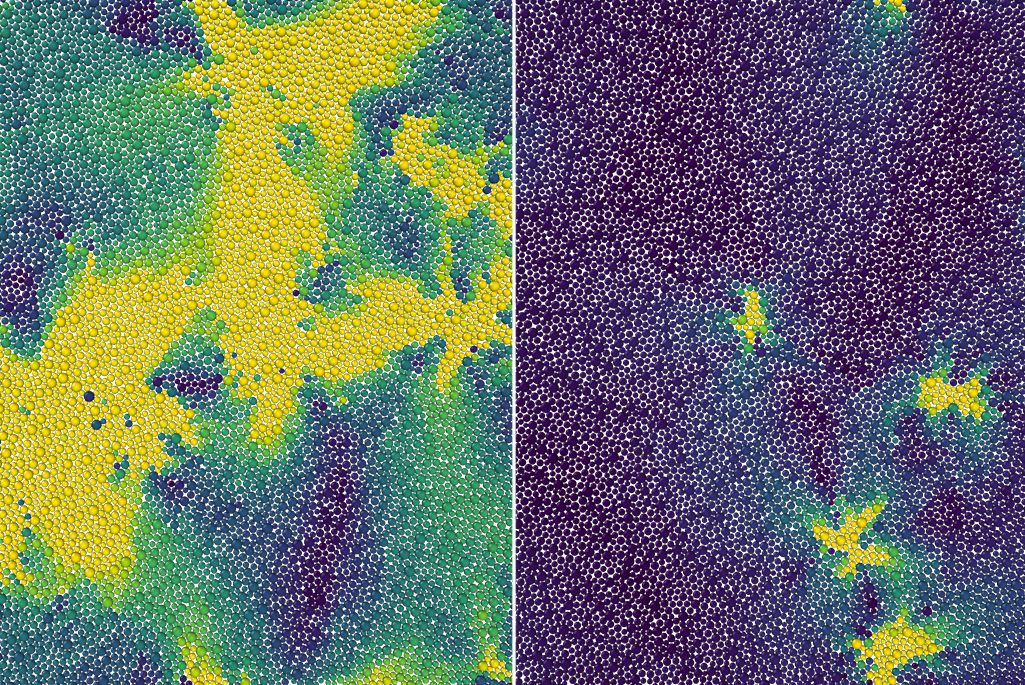

Specifically, using theory, computer simulations, and previous experiments, the scientists explained why the molecules in these materials, when cooled, remain disordered like a liquid until taking a sharp turn toward a solid-like state at a certain temperature called the onset temperature – effectively becoming so viscous that they barely move. This onset of rigidity – a previously unknown phase transition – is what separates supercooled from normal liquids.

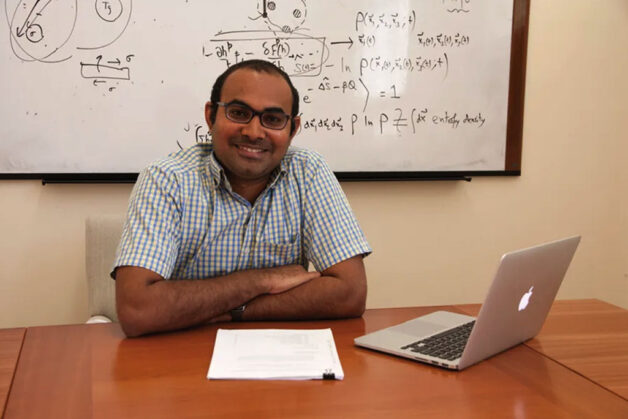

Kranthi Mandadapu (Credit: Kranthi Mandadapu)

“Our theory predicts the onset temperature measured in model systems and explains why the behavior of supercooled liquids around that temperature is reminiscent of solids even though their structure is the same as that of the liquid,” said Kranthi Mandadapu, a staff scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division and professor of chemical engineering at the University of California, Berkeley, who led the work which was published in PNAS.

Any supercooled liquid continuously jumps between multiple configurations of molecules, resulting in localized particle movements known as excitations. In their proposed theory, Mandadapu, postdoctoral researcher Dimitrios Fraggedakis, and graduate student Muhammad Hasyim treated the excitations in a 2D supercooled liquid as though they were defects in a crystalline solid. As the supercooled liquid’s temperature increased to the onset temperature, they propose that every instance of a bound pair of defects broke apart into an unbounded pair. At precisely this temperature, the unbinding of defects is what made the system lose its rigidity and begin to behave like a normal liquid.

“The onset temperature for glassy dynamics is like a melting temperature that ‘melts’ a supercooled liquid into a liquid. This should be relevant for all supercooled liquids or glassy systems,” said Mandadapu.

“The whole quest is to understand microscopically what separates the supercooled liquid and a high temperature liquid.”

– Kranthi Mandadapu

The theory and simulations captured other key properties of glassy dynamics, including the observation that, over short periods of time, a few particles moved while the rest of the liquid remained frozen.

“The whole quest is to understand microscopically what separates the supercooled liquid and a high temperature liquid,” said Mandadapu.

Mandadapu and his colleagues believe they will be able to extend their model to 3D systems. They also intend to expand it to explain just how localized motions lead to further nearby excitations resulting in the relaxation of the entire liquid. Together, these components could provide a consistent microscopic picture of how glassy dynamics emerge in a way that aligns with state-of-the-art observations.

“It’s fascinating from a basic science point of view to examine why these supercooled liquids exhibit remarkably different dynamics than the regular liquids that we know,” said Mandadapu.

This research was funded by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.