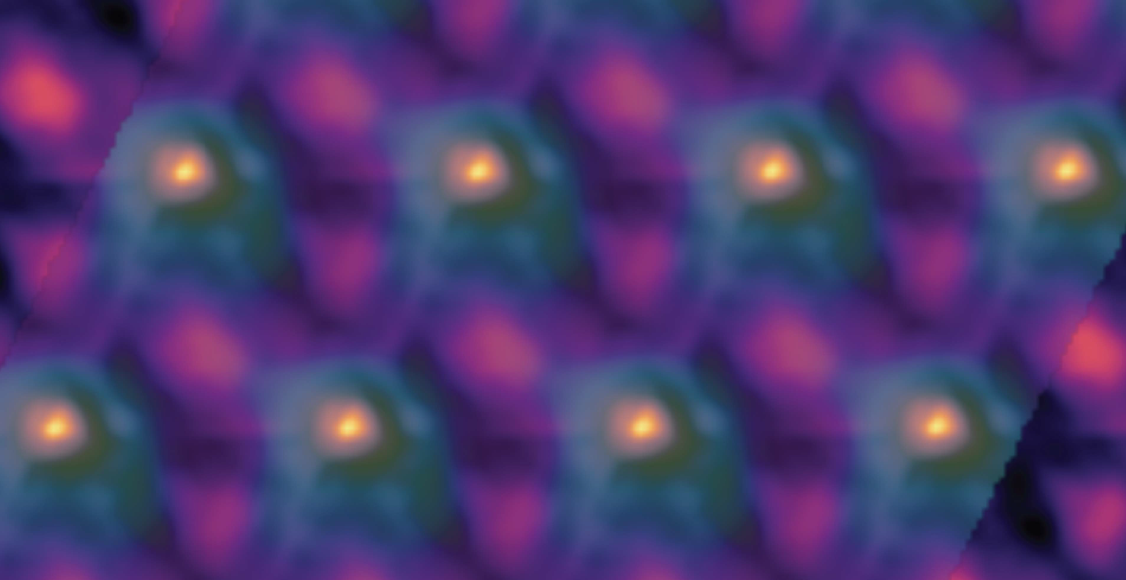

In a new study, scientists have observed long-lived excitons in a topological material, opening intriguing new research directions for optoelectronics and quantum computing.

Excitons are charge-neutral quasiparticles created when light is absorbed by a semiconductor. Consisting of an excited electron coupled to a lower-energy electron vacancy or hole, an exciton is typically short-lived, surviving only until the electron and hole recombine, which limits its usefulness in applications.

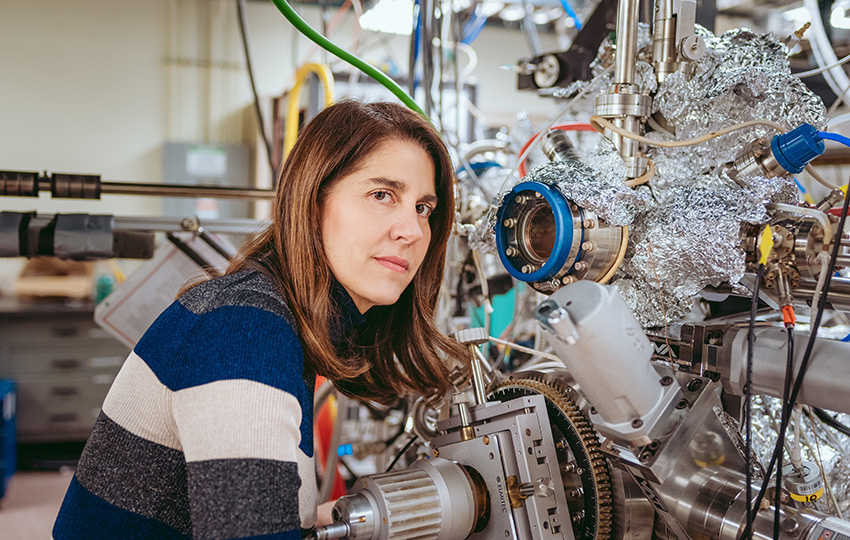

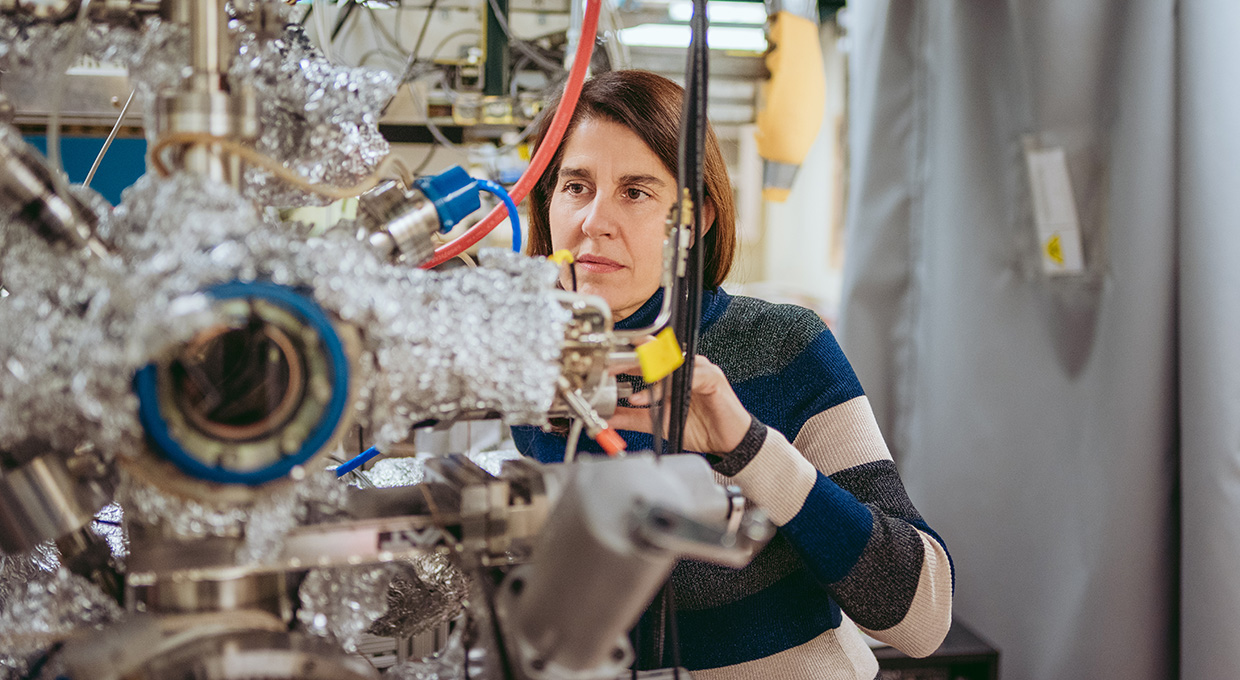

“If we want to make progress in quantum computing and create more sustainable electronics, we need longer exciton lifetimes and new ways of transferring information that don’t rely on the charge of electrons,” said Alessandra Lanzara, who led the study. Lanzara is a senior faculty scientist at the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and a UC Berkeley physics professor. “Here we’re leveraging topological material properties to make an exciton that is long lived and very robust to disorder.”

In a topological insulator, electrons can only move on the surface. By creating an exciton in such a material, the researchers hoped to achieve a state in which an electron trapped on the surface was coupled to a hole that remained confined in the bulk. Such a state would be spatially indirect – extending from the surface into the bulk – and could retain the special spin properties inherent to topological surface states.

“If we want to make progress in quantum computing and create more sustainable electronics, we need longer exciton lifetimes and new ways of transferring information that don’t rely on the charge of electrons.”

– Alessandra Lanzara

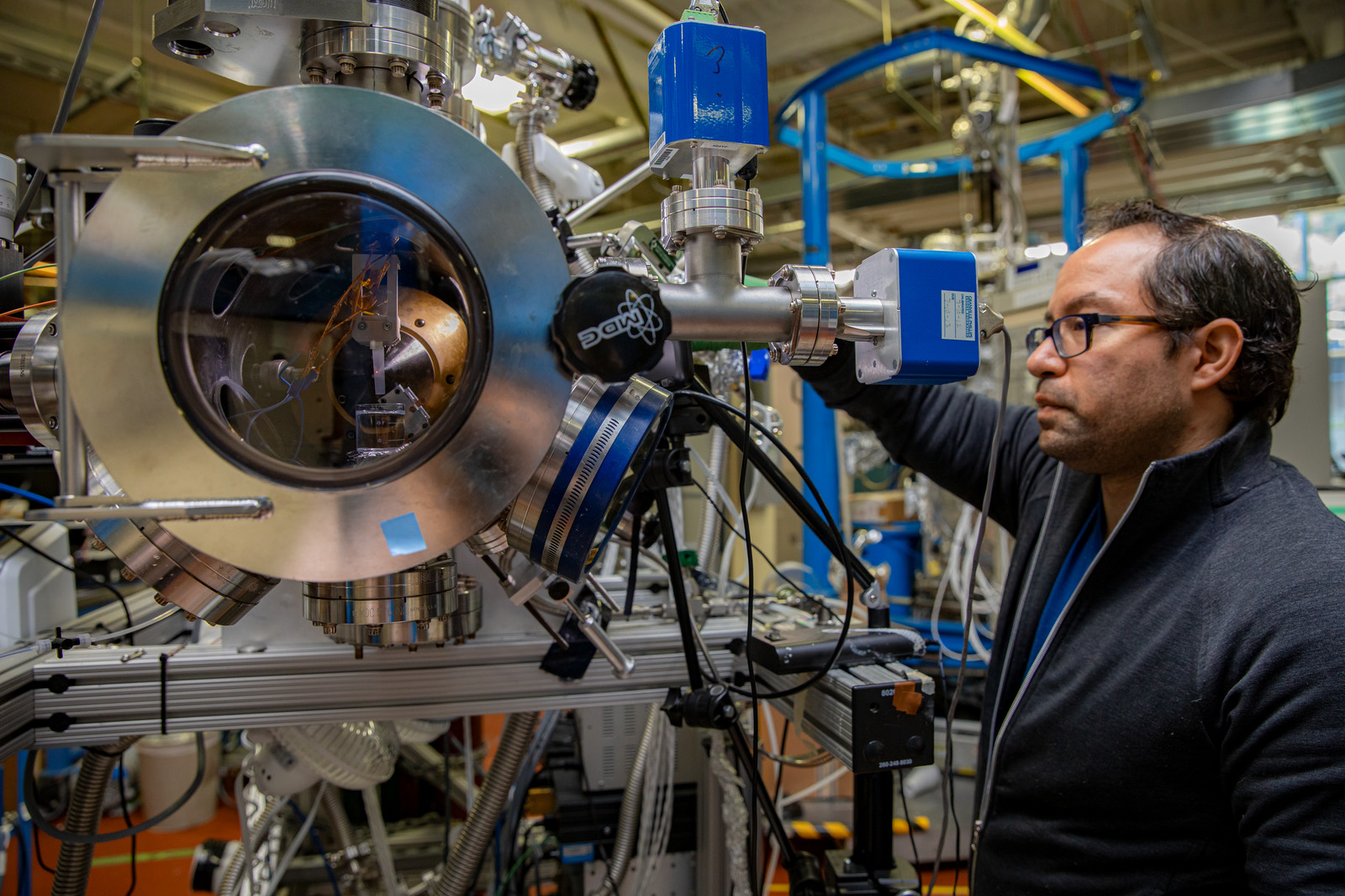

The team used a state-of-the-art technique that Lanzara helped pioneer, known as time-, spin-, and angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy, which uses ultrafast pulses of light to probe the properties of electrons in a material. They worked with bismuth telluride, a well-studied topological insulator that offered the precise properties they needed: an electronic state combining the topological surface characteristics with those of the insulating bulk.

“We knew that bismuth telluride had the right electronic structure to support a spatially indirect exciton, but finding the right experimental conditions took hundreds of hours,” said Lanzara. “It was a huge joy for everyone when we saw the excitonic state we were looking for.”

The team studied the formation of the excitonic state and characterized its interaction with other charge carriers in the material. These observations already constituted a breakthrough, but the team went a step further by also measuring the state’s spin character and demonstrating the persistence of the topological material’s strong spin polarization in the excitonic state.

“We studied this new excitonic state and found that it does indeed inherit characteristics of both excitons and topological states,” said first-author Ryo Mori, who worked on this project as a postdoctoral scholar and is now a faculty member at the University of Tokyo. “This finding opens up opportunities for future applications that combine properties of both, such as opto-spintronics and possibly new quantum information technology.”

“This work is just the beginning, and many mysteries remain in the fundamental properties,” Mori continued. “For example, we still cannot conclude the hole’s spin in the current measurement. How does spin affect the exciton pairing mechanism? And then, how do we control the properties of this state so we can use it in an application?”

The team’s findings are described in a paper published in the journal Nature. Co-authors include researchers from Berkeley Lab, UC Berkeley, and the University of Tokyo.

The research was supported by the Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

# # #

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.