Key Takeaways

- Breakthrough offers sustainable alternatives to chemical manufacturing processes that typically rely on fossil fuels.

- Harnessing biological processes in bacteria could offer more environmentally friendly approach to chemical synthesis.

- Replaces expensive chemical reactants with natural products that can be produced by bacteria.

A research team led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and UC Berkeley has engineered bacteria to produce new-to-nature carbon products that could provide a powerful route to sustainable biochemicals.

The advance – which was recently announced in the journal Nature – uses bacteria to combine natural enzymatic reactions with a new-to-nature reaction called the “carbene transfer reaction.” This work could also one day help reduce industrial emissions because it offers sustainable alternatives to chemical manufacturing processes that typically rely on fossil fuels.

“What we showed in this paper is that we can synthesize everything in this reaction – from natural enzymes to carbenes – inside the bacterial cell. All you need to add is sugar and the cells do the rest,” said Jay Keasling, a principal investigator of the study and CEO of the Department of Energy’s Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI).

Carbenes are highly reactive carbon-based chemicals that can be used in many different types of reactions. For decades, scientists have wanted to use carbene reactions in the manufacturing of fuels and chemicals, and in drug discovery and synthesis.

“All you need to add is sugar and the cells do the rest.”

– Jay Keasling, principal investigator and CEO of the Department of Energy’s Joint BioEnergy Institute (JBEI)

But these carbene processes could only be carried out in small batches via test tubes and required expensive chemical substances to drive the reaction.

In the new study, the researchers replaced expensive chemical reactants with natural products that can be produced by an engineered strain of the bacteria Streptomyces. Because the bacteria use sugar to produce chemical products through cellular metabolism, “this work enables us to perform the carbene chemistry without toxic solvents or toxic gases typically used in chemical synthesis,” said first author Jing Huang, a Berkeley Lab postdoctoral researcher in the Keasling Lab. “This biological process is much more environmentally friendly than the way chemicals are synthesized today,” Huang said.

During experiments at JBEI, the researchers observed the engineered bacterium as it metabolized and converted sugars into the carbene precursor and the alkene substrate. The bacterium also expressed an evolved P450 enzyme that used those chemicals to produce cyclopropanes, high-energy molecules that could potentially be used in the sustainable production of novel bioactive compounds and advanced biofuels. “We can now perform these interesting reactions inside the bacterial cell. The cells produce all of the reagents and the cofactors, which means that you can scale this reaction to very large scales” for mass manufacturing, Keasling said.

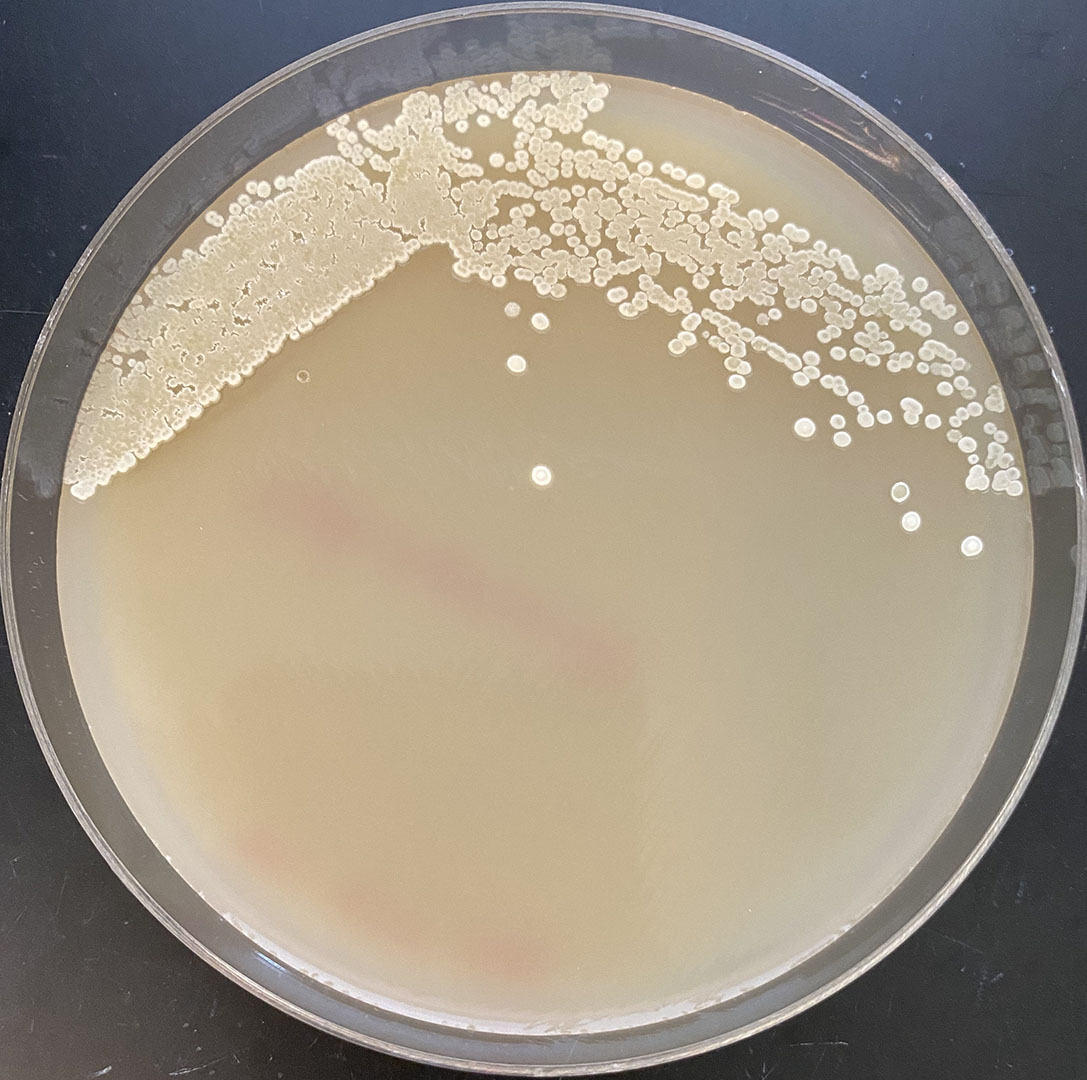

During experiments at DOE’s Joint BioEnergy Institute, researchers observed an engineered strain of the bacteria Streptomyces as it produced cyclopropanes, high-energy molecules that could potentially be used in the sustainable production of novel bioactive compounds and advanced biofuels. (Image courtesy of Jing Huang)

Recruiting bacteria to synthesize chemicals could also play an integral role in reducing carbon emissions, Huang said. According to other Berkeley Lab researchers, close to 50% of greenhouse gas emissions come from the production of chemicals, iron and steel, and cement. Limiting global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels will require severely cutting greenhouse gas emissions in half by 2030, says a recent report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

Huang said that while this fully integrated system can be envisioned for a large number of carbene donor molecules and alkene substrates, it is not yet ready for commercialization.

“For every new advance, someone needs to take the first step. And in science, it can take years before you succeed. But you have to keep trying – we can’t afford to give up. I hope our work will inspire others to continue searching for greener, sustainable biomanufacturing solutions,” Huang said.

Other authors on the paper are Andrew Quest, Pablo Cruz-Morales, Kai Deng, Jose Henrique Pereira, Devon Van Cura, Ramu Kakumanu, Edward E. K. Baidoo, Qingyun Dan, Yan Chen, Christopher J. Petzold, Trent R. Northen, Paul D. Adams, Douglas S. Clark, Emily P. Balskus, John F. Hartwig, and Aindrila Mukhopadhyay.

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science and DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research. Additional support was provided by the National Science Foundation.

###

Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest scientific challenges are best addressed by teams, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Today, Berkeley Lab researchers develop sustainable energy and environmental solutions, create useful new materials, advance the frontiers of computing, and probe the mysteries of life, matter, and the universe. Scientists from around the world rely on the Lab’s facilities for their own discovery science. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory, managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.