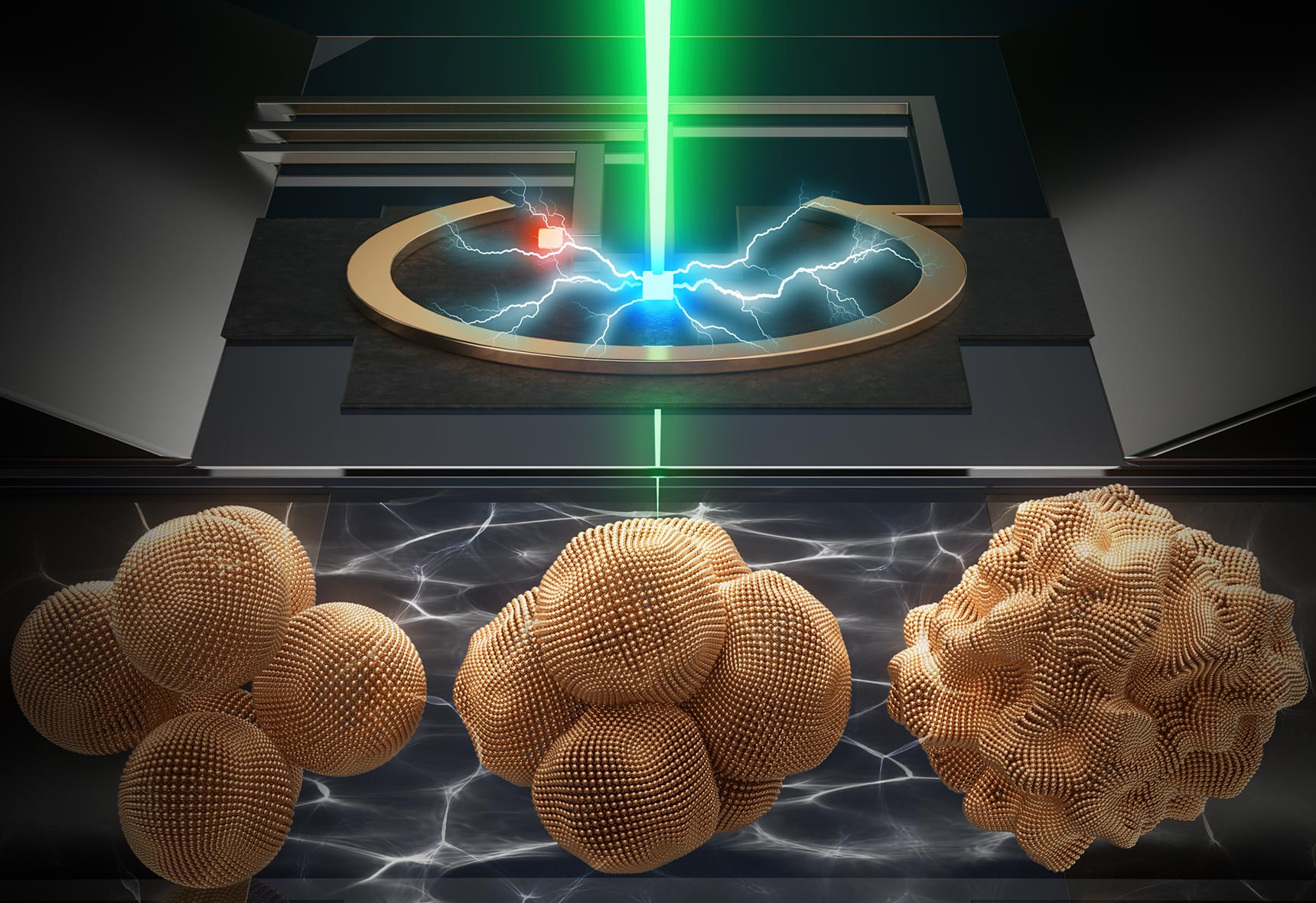

Some parts of the world have been so successful in making inexpensive renewable electricity that we occasionally have too much of it. One possible use for that low-cost energy: Converting carbon dioxide into fuel and other products using a device called a membrane-electrode assembly.

A team of scientists from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) and the University of California Berkeley have developed a new approach to understanding this promising technology via physics modeling. The paper, which was recently published in the journal Nature Chemical Engineering, could help scientists learn how to improve membrane-electrode assembly efficiency.

Carbon dioxide can be transformed into valuable feedstocks such as carbon monoxide and ethylene, which manufacturers use to make products including chemicals and packaging. One way to do this is with membrane-electrode assemblies, which are devices that consist of two electrodes separated by a membrane. Also used in fuel cells that turn inputs like hydrogen into electricity, membrane-electrode assemblies hold promise for being able to use surplus renewable power to run reaction sequences that catalyze carbon dioxide into other chemicals. But these devices have problems with efficiency, and their workings are not yet fully understood.

“Membrane-electrode assemblies are complicated systems with multiple layers. Each layer holds different chemical species, additives, and particles,” said Adam Weber, a senior scientist at Berkeley Lab and corresponding author of the study. “Often, we don’t really know why experiments with membrane-electrode assemblies produce certain products, or why they fail to convert a larger percentage of a given amount of carbon dioxide.”

Computer modeling can help predict which device parameters will produce the best results, but they tend to be less accurate at anticipating issues such as crossover, which is when carbon dioxide moves across the membrane instead of reacting. To improve model accuracy, the researchers turned to Marcus–Hush–Chidsey kinetics, a theory that previously had not been integrated into membrane-electrode assembly modeling and is shown to be critical for understanding the reaction mechanism.

The researchers validated their model against experimental data, finding that it did a better job of predicting real-world outcomes than previous models. Among other advantages, the use of Marcus–Hush–Chidsey kinetics made it possible to account for the role of water orientation.

“Having a digital twin of a system allows you to probe a much larger parameter space much more rapidly than in experiments, which are typically complex and require special equipment. We can’t see where every molecule is in an experiment. But in a model, we can.”

– Adam Weber

The team then ran virtual experiments with its model to explore how different membrane-electrode assembly designs performed in terms of carbon-dioxide utilization and selectivity for desired products. “With this work, we have shown how you can leverage chemical engineering principles toward these advanced technologies that are coming online,” he said. “That gives us insights and ideas for optimizing these cell designs and materials so we can go forward and make them.”

Some of the variables the team tested virtually included catalyst-layer thickness and catalyst-specific surface area. They also uncovered design rules around the importance of coupled ion and water transport, as well as tradeoffs between transport phenomena and reaction and buffer kinetics. All of these change the overall energy efficiency, products obtained, and amount of carbon dioxide converted.

“Having a digital twin of a system allows you to probe a much larger parameter space much more rapidly than in experiments, which are typically complex and require special equipment,” Weber said, adding, “We can’t see where every molecule is in an experiment. But in a model, we can.”

Weber said the next step in the research is to increase the model’s complexity to be able to look at performance over a membrane-electrode assembly’s lifetime, among other variables.

This research was supported in part by the Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office and Berkeley Lab’s Laboratory Directed Research and Development Grant.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to delivering solutions for humankind through research in clean energy, a healthy planet, and discovery science. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Researchers from around the world rely on the Lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

Making Renewable, Infinitely Recyclable Plastics Using Bacteria

How a Record-Breaking Copper Catalyst Converts CO2 Into Liquid Fuels