Magnets are essential across scientific applications, particularly in particle physics and in light sources. At Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), Soren Prestemon leads cutting-edge research in magnet technology as the director of the Berkeley Center for Magnet Technology and the U.S. Magnet Development Program.

Featuring:

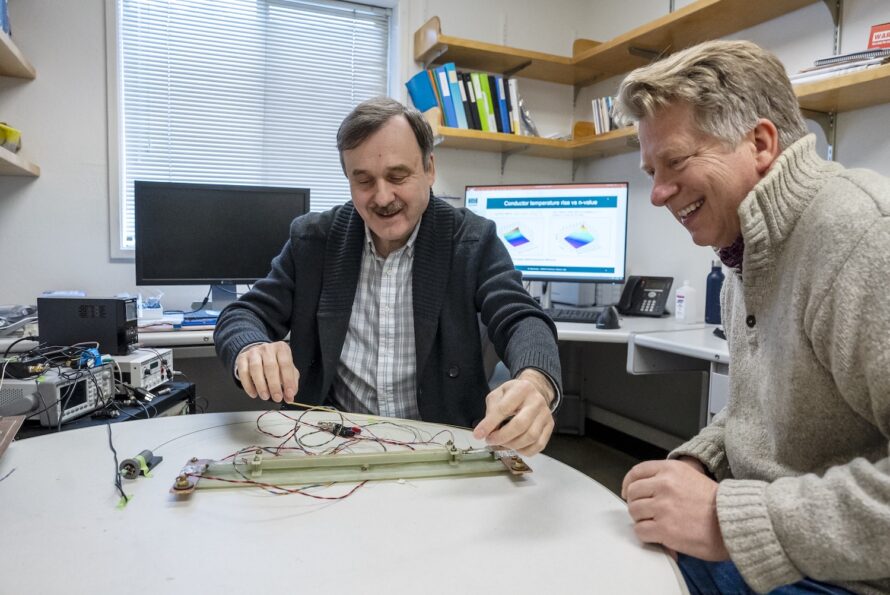

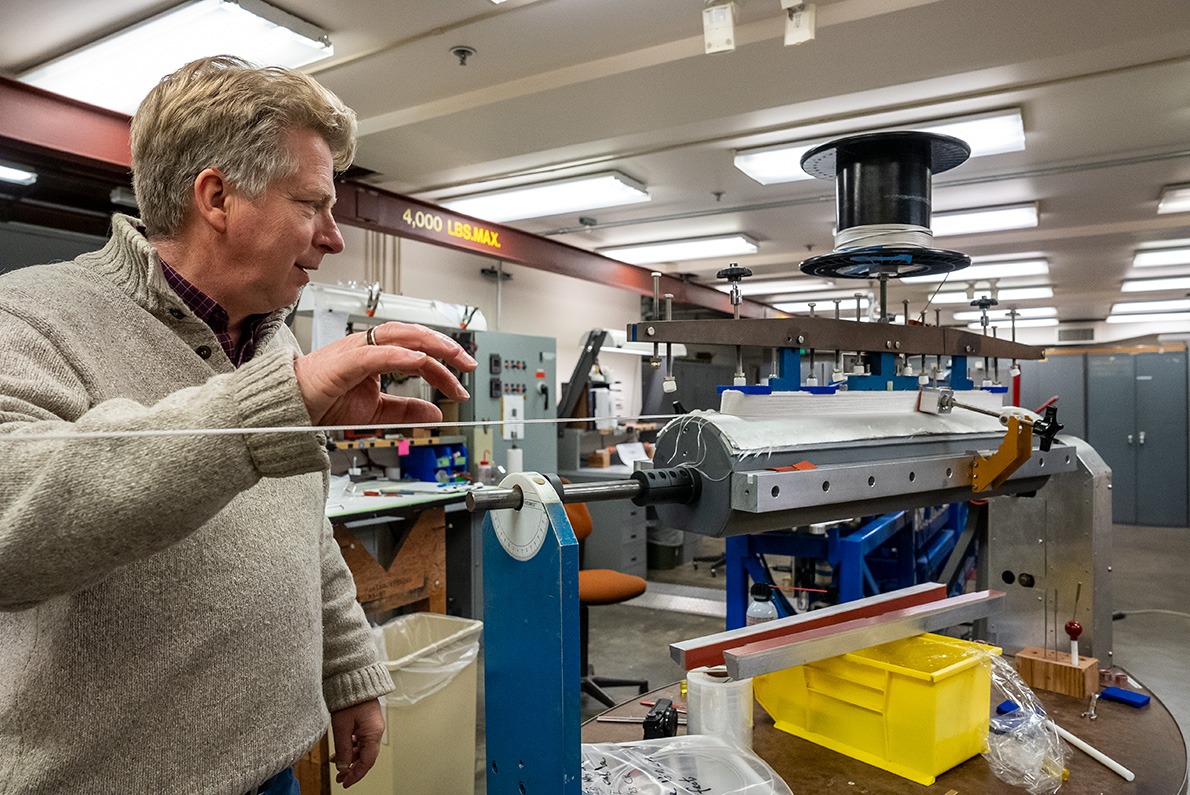

Soren Prestemon, division deputy for technology at Berkeley Lab’s Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics Division, and director of the Berkeley Center for Magnet Technology and the U.S. Magnet Development Program.

[00:00:00] Jenny Nuss: Hi, and welcome. I’m Jenny Nuss, a science communicator at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and today we’ll be exploring our magnet research program. We’ll learn a little bit about the history, hear about the ongoing efforts, and get a peak at what’s ahead. Our guest today is Soren Prestemon. Soren is the division deputy for technology in our Accelerator Technology and Applied Physics division.

He’s also the director of the Berkeley Center for Magnet Technology, and he serves as the director for the U.S. Magnet Development Program. Welcome Soren, and thanks for taking the time to chat.

[00:00:44] Soren Prestemon: It’s great to be here. Thanks for the invitation.

[00:00:47] Jenny Nuss: So, let’s set the scene. I think a lot of people, when they think of magnets, think of the ones on their refrigerator, but that’s not necessarily what we’re doing here at the national lab.

So, why are we studying magnets and what are we using them for?

[00:01:01] Soren Prestemon: The magnets in the refrigerator aren’t too far from some of what we do here. Just we do that kind of on steroids, if you will. And then there’s other forms of magnets that we work with where we are transporting current through a wire to make a magnetic field.

But why do we use magnets? It’s basically that magnetic fields interact with charged particles to create a force that’s orthogonal to the magnetic field and to the motion of the charged particle. So, if you have a fast-moving charged particle and you apply a magnetic field to that, the charged particle gets bent or steered in different directions.

And so, really, we use magnets as optics for charged particles. That enables all kinds of science applications with charged particles – like light sources. The Advanced Light Source at Berkeley, the cyclotron down at the cyclotron, and high-energy physics – so, colliders like the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

[00:01:56] Jenny Nuss: So Soren, can you provide a little bit of history of Berkeley Lab’s role in magnet research?

[00:02:01] Soren Prestemon: Yeah, so magnets are kind of front and center with Berkeley since the inception of Lab. If you go way back, it has a long and illustrious history with particle accelerators. Ernest Lawrence invented the cyclotron and the cyclotron, at its heart, has a magnet. That enabled the existence of the cyclotron.

And so, right from the get go, magnets have been part of Berkeley’s history. And he (Lawrence) got the Nobel Prize in 1939 for that. And, you know, since then it’s kind of been the father of team science here at Berkeley. And a big part of that is colliders, or accelerators, of various flavors throughout Berkeley’s history. Both at Berkeley, but then, helping other labs build accelerators – first for nuclear science, but ultimately for high-energy physics and other applications… as well as industry and medical applications, for example.

So, there’s a long history of Berkeley, of magnets, and applying magnets for science.

[00:02:57] Jenny Nuss: So, it sounds like our magnet research program goes way back, but I know we still have a strong program today. Can you give a high-level overview of where we’re at right now?

[00:03:07] Soren Prestemon: Yeah, so our program is kind of broadband.

There are a couple of major focuses. One is on permanent magnets that date back to the work of Klaus Halbach, who invented permanent magnet technology for science applications. This technology enabled undulation, which in turn enabled third-generation light sources, and later, free-electron lasers, considered the fourth-generation light sources of today.

And we continue to do research in that area and apply it to light sources. We’ve provided, for example, the undulators for the LCLS and LCLS-2, the high-energy upgrade at SLAC. We also do undulators for the Advanced Light Source here at Berkeley. Additionally, we conduct a lot of research in superconducting magnets for science applications, particularly for high-energy physics.

So, there we use superconductors – conductors that carry current with zero loss. By taking superconducting wires and making them into magnets, we can create a magnetic field without incurring losses in the form of heat. So, we don’t have power loss, energy loss or energy consumption in operating these magnets, other than the energy needed to keep them cold.

And these superconductors allow us to achieve very high magnetic fields, which is critical to enabling future colliders or the colliders we have today. For example, the LHC is based on niobium-titanium, a type of superconductor. The superconducting magnets in the LHC are made from that wire. Currently, we’re in the process of upgrading the LHC using a next-generation, low-temperature superconductor, which enables higher fields.

It still operates at 1.9 Kelvin, but it allows us to increase luminosity, the number of interactions happening at the LHC, also known as the Large Hadron Collider. That maximizes the physics output of the facility. We’re further working on niobium magnet technology for the next generation of colliders beyond the LHC.

Berkeley is at the forefront of that in the US, with Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory leading the magnet development program and national effort to develop niobium magnet technology for future colliders. That collider may be a muon collider, which collides special charged particles called muons. Or it may be a future hadron collider, which would be similar to the LHC but on a much larger scale and with higher energies to probe deeper into the realm of high-energy physics.

[00:05:37] Jenny Nuss: It sounds like superconducting magnets have a lot of practical science applications, but with that, I assume that there are a lot of challenges that come up when you’re studying these. So, can you tell me a little bit about that?

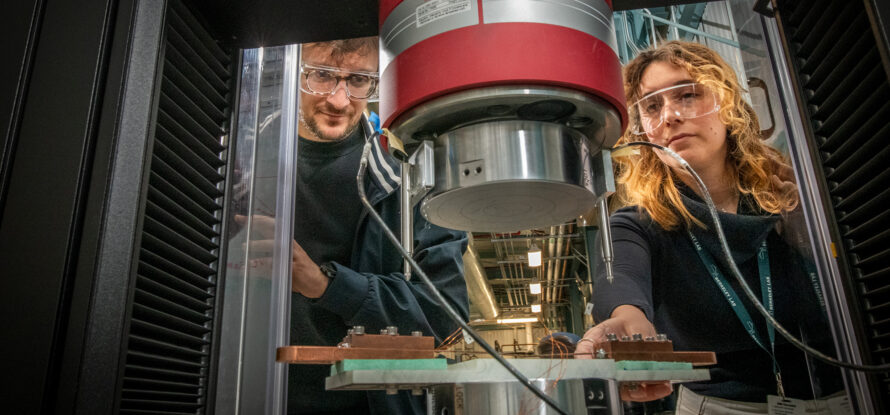

[00:05:49] Soren Prestemon: There are many challenges that we work to address. Among them are the forces and stresses on these conductors. These conductors are brittle. Perhaps foremost is protecting the magnets. By that, we mean we can have a loss of superconducting state. A small amount of heat deposited on the system can cause it to lose its superconducting state.

When that occurs, the stored energy in the magnet is converted to heat at the location where we’ve lost the superconducting state. That can easily burn up the magnet or conductor in that location and completely ruin the magnet. So, protecting the magnets is a huge challenge.

It’s integral to the design and fabrication of systems. That’s one of the driving challenges, especially for high-temperature superconductors, where the loss of superconductivity remains very localized and is very hard to detect. Much of our research is focused on developing new diagnostics and instrumentation that would allow us to see precursors to that loss of superconductivity. The goal is to act before we enter the regime where the magnet can be damaged.

[00:07:02] Jenny Nuss: So now that we’ve talked about why we study magnets, we’ve talked about our history and the challenges, what’s on the horizon for magnet research?

[00:07:12] Soren Prestemon: I think we’re entering a golden era for magnet technology, looking forward on multiple fronts, especially for applications. The reason I say that is that breakthroughs may be imminent on both the permanent magnet and superconducting magnet sides. On the permanent magnet side, light sources have been using permanent magnets primarily in areas we call insertion devices.

So you have the main facility operating with resistive magnets traditionally, and then we use permanent magnets for specific applications that are kind of inserted into the system, but they’re not integral to the system. And I think the next generation of light sources will be permanent magnet-based.

That’s my crystal ball. Permanent magnets offer the opportunity for dramatically more compact magnets. They consume no energy, so the operating cost is reduced. They’re very stable, and I expect them to be ultimately a lot more cost-effective.

In my view, next-generation light sources – storage ring-type light sources – will be permanent magnet-based. In the superconducting realm, the big questions are the cost of superconductors and whether the magnet technology to use those advanced superconductors is ready.

If the cost of superconductors comes down below a certain threshold, all kinds of applications open up and it becomes competitive. Once something becomes competitive, the market grows and the cost is driven down further. We’re at the cusp of that with high-temperature superconductors, and everybody’s putting a lot of hope in fusion. The startup fusion companies are trying to use REBCO, one of these high-temperature superconductors, and that is driving the cost down. It’s come down already by a factor of three or so over the last six years. If that trend continues, we will see a sudden explosion in the market for the use of these superconductors.

Berkeley is at the forefront of groups trying to develop the magnet technology to use these superconductors, so that when the cost becomes competitive, the technology is ready.

[00:09:40] Jenny Nuss: Well, on that note, I’ve certainly learned a lot, and you’ve made a magnet fan out of me.

[00:09:47] Soren Prestemon: Welcome aboard to the Magnet community!

[00:09:51] Jenny Nuss: Thank you so much for taking the time to talk with me.

[00:09:54] Soren Prestemon: Thank you. Thank you very much.

[00:09:56] Jenny Nuss: If you’d like to learn more about our research, visit lbl.gov. This is Jenny from Berkeley Labs strategic communications team signing-off.

Leading the Field in Magnets

What Is a Superconductor Quench?