Key Takeaways

- Scientists have discovered “berkelocene,” the first organometallic molecule to be characterized containing the heavy element berkelium.

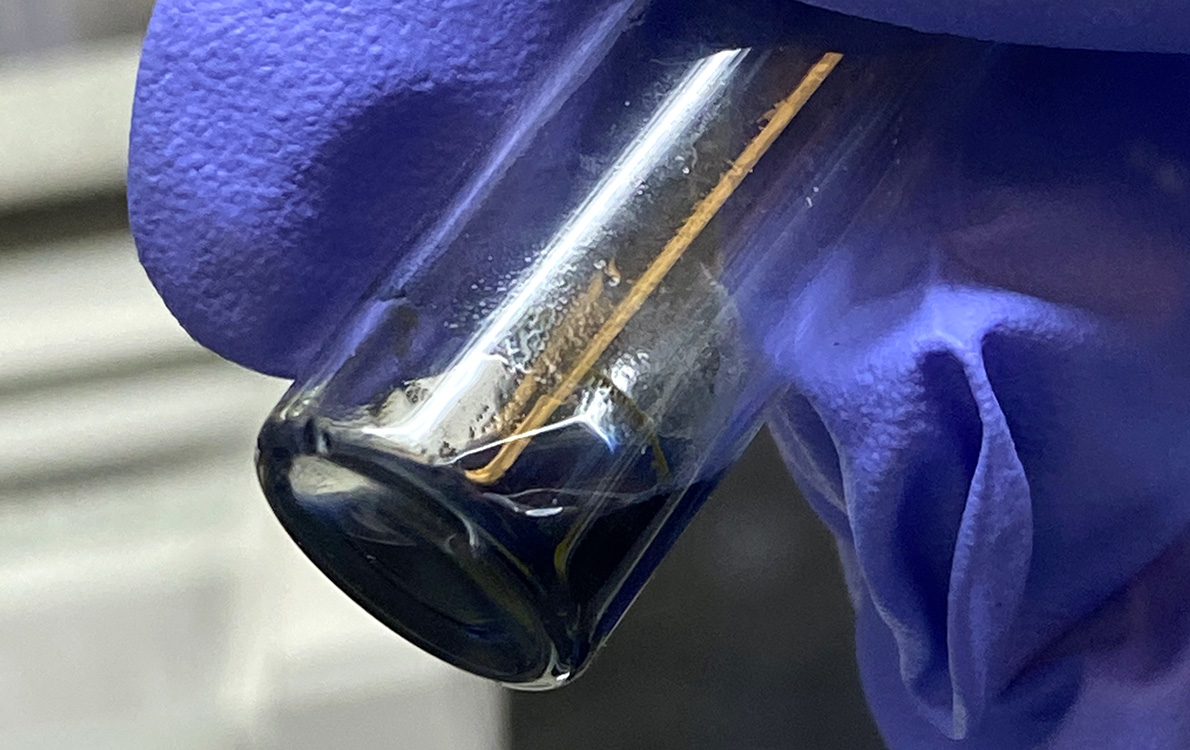

- The extremely oxygen- and water-sensitive complex was formed from 0.3 milligram of berkelium-249 using specialized facilities for handling air-sensitive and radioactive materials.

- The breakthrough disrupts long-held theories about the chemistry of the elements that follow uranium in the periodic table.

A research team led by the Department of Energy’s Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has discovered “berkelocene,” the first organometallic molecule to be characterized containing the heavy element berkelium.

Organometallic molecules, which consist of a metal ion surrounded by a carbon-based framework, are relatively common for early actinide elements like uranium (atomic number 92) but are scarcely known for later actinides like berkelium (atomic number 97).

“This is the first time that evidence for the formation of a chemical bond between berkelium and carbon has been obtained. The discovery provides new understanding of how berkelium and other actinides behave relative to their peers in the periodic table,” said Stefan Minasian, a scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division and one of four co-corresponding authors of a new study published in the journal Science.

A heavy metal molecule with Berkeley roots

Berkelium is one 0f 15 actinides in the periodic table’s f-block. One row above the actinides are the lanthanides.

The pioneering nuclear chemist Glenn Seaborg discovered berkelium at Berkeley Lab in 1949. It would become just one of many achievements that led to his winning the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with fellow Berkeley Lab scientist Edwin McMillan for their discoveries in the chemistry of the transuranium elements.

“This is the first time that evidence for the formation of a chemical bond between berkelium and carbon has been obtained.”

– Stefan Minasian, Chemical Sciences Division staff scientist

For many years, the Heavy Element Chemistry group in Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division has been dedicated to preparing organometallic compounds of the actinides, because these molecules typically have high symmetries and form multiple covalent bonds with carbon, making them useful for observing the unique electronic structures of the actinides.

“When scientists study higher symmetry structures, it helps them understand the underlying logic that nature is using to organize matter at the atomic level,” Minasian said.

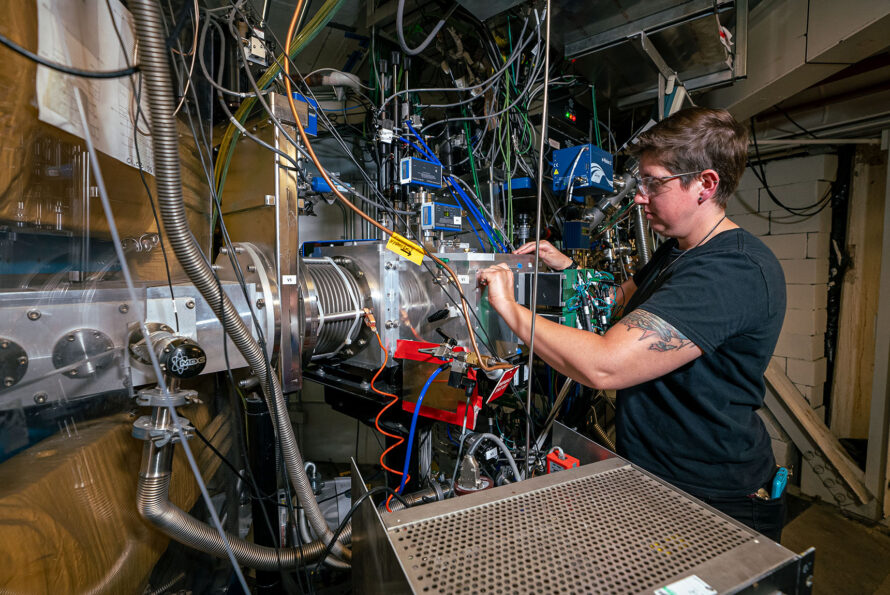

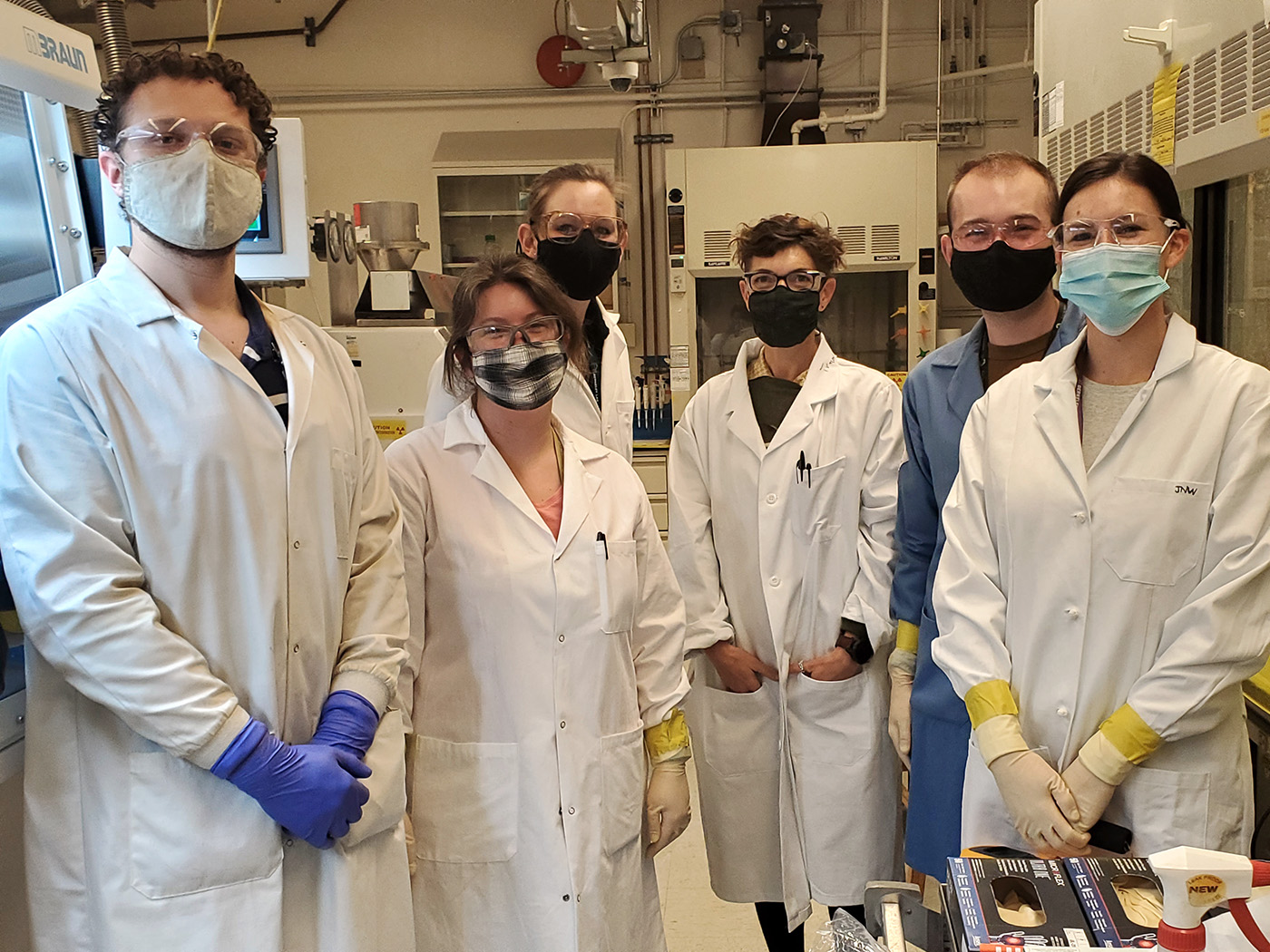

From left: Dominic Russo, Amy Price, Alyssa Gaiser, Polly Arnold, Jacob Branson, and Jennifer Wacker at Berkeley Lab’s Heavy Element Research Laboratory. They are co-authors on a new study published in Science, which reported their discovery of the heavy-metal molecule berkelocene. (Credit: Stefan Minasian/Berkeley Lab)

But berkelium is not easy to study because it is highly radioactive. And only very minute amounts of this synthetic heavy element are produced globally every year. Adding to the difficulty, organometallic molecules are extremely air-sensitive and can be pyrophoric.

“Only a few facilities around the world can protect both the compound and the worker while managing the combined hazards of a highly radioactive material that reacts vigorously with the oxygen and moisture in air,” said Polly Arnold, a co-corresponding author on the paper who is a UC Berkeley professor of chemistry and director of Berkeley Lab’s Chemical Sciences Division.

Breaking down the berkelium barrier

So Minasian, Arnold, and co-corresponding author Rebecca Abergel, a UC Berkeley associate professor of nuclear engineering and of chemistry who leads the Heavy Element Chemistry Group at Berkeley Lab, assembled a team to overcome these obstacles.

At Berkeley Lab’s Heavy Element Research Laboratory, the team custom-designed new gloveboxes enabling air-free syntheses with highly radioactive isotopes. Then, with just 0.3 milligram of berkelium-249, the researchers conducted single-crystal X-ray diffraction experiments. The isotope that was acquired by the team was initially distributed from the National Isotope Development Center, which is managed by the DOE Isotope Program at Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

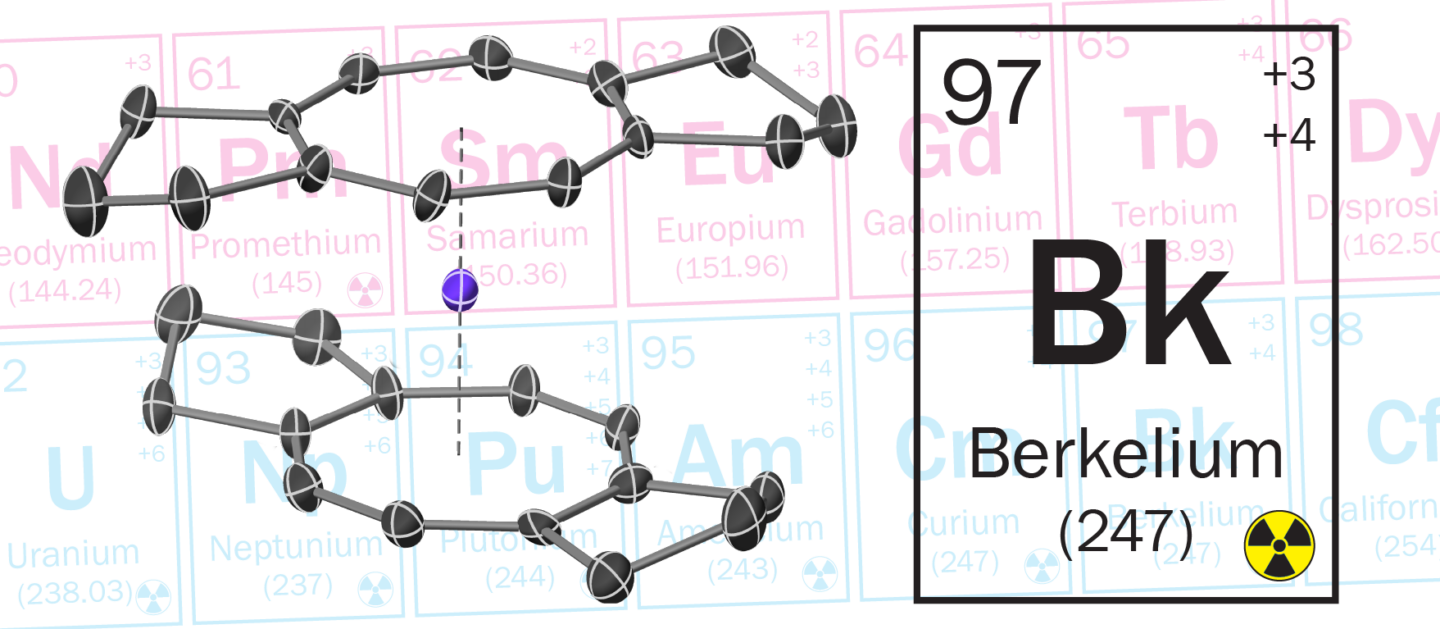

The results showed a symmetrical structure with the berkelium atom sandwiched between two 8-membered carbon rings. The researchers named the molecule “berkelocene,” because its structure is analogous to a uranium organometallic complex called “uranocene.” (UC Berkeley chemists Andrew Streitwieser and Kenneth Raymond discovered uranocene in the late 1960s.)

In an unexpected finding, electronic structure calculations performed by co-corresponding author Jochen Autschbach at the University of Buffalo revealed that the berkelium atom at the center of the berkelocene structure has a tetravalent oxidation state (positive charge of +4), which is stabilized by the berkelium–carbon bonds.

“Traditional understanding of the periodic table suggests that berkelium would behave like the lanthanide terbium,” said Minasian.

“But the berkelium ion is much happier in the +4 oxidation state than the other f-block ions we expected it to be most like,” Arnold said.

The researchers say that more accurate models showing how actinide behavior changes across the periodic table are needed to solve problems related to long-term nuclear waste storage and remediation. “This clearer portrait of later actinides like berkelium provides a new lens into the behavior of these fascinating elements,” Abergel said.

This work was supported by the DOE Office of Science.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to groundbreaking research focused on discovery science and solutions for abundant and reliable energy supplies. The lab’s expertise spans materials, chemistry, physics, biology, earth and environmental science, mathematics, and computing. Researchers from around the world rely on the lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.