A team led by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) has invented a technique to study electrochemical processes at the atomic level with unprecedented resolution and used it to gain new insights into a popular catalyst material. Electrochemical reactions – chemical transformations that are caused by or accompanied by the flow of electric currents – are the basis of batteries, fuel cells, electrolysis, and solar-powered fuel generation, among other technologies. They also drive biological processes such as photosynthesis and occur under the Earth’s surface in the formation and breakdown of metal ores.

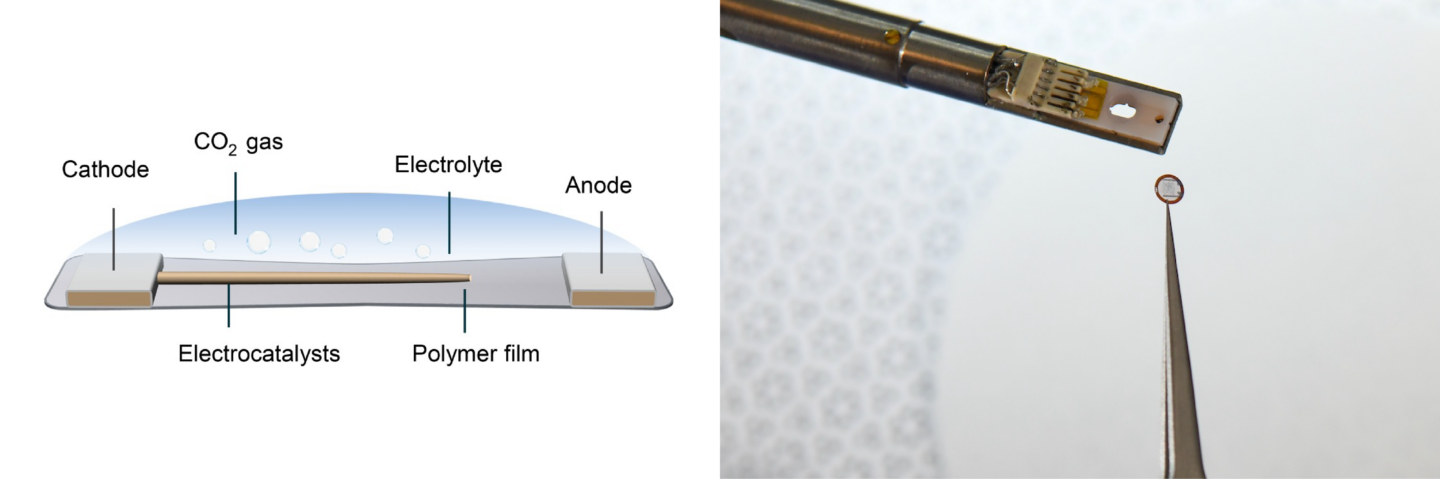

The scientists have developed a cell – a small enclosed chamber that can hold all the components of an electrochemical reaction – that can be paired with transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to generate precise views of a reaction at atomic scale. Better yet, their device, which they call a polymer liquid cell (PLC), can be frozen to stop the reaction at specific timepoints, so scientists can observe composition changes at each stage of a reaction with other characterization tools. In a paper published June 19 in Nature, the team describes their cell and a proof of principle investigation using it to study a copper catalyst that reduces carbon dioxide to generate fuels.

“This is a very exciting technical breakthrough that shows something we could not do before is now possible. The liquid cell allows us to see what’s going on at the solid-liquid interface during reactions in real time, which are very complex phenomena. We can see how the catalyst surface atoms move and transform into different transient structures when interacting with the liquid electrolyte during electrocatalytic reactions,” said Haimei Zheng, lead author and senior scientist in Berkeley Lab’s Materials Science Division.

“It’s very important for catalyst design to see how a catalyst works and also how it degrades. If we don’t know how it fails, we won’t be able to improve the design. And we’re very confident we’re going to see that happen with this technology,” said co-first author Qiubo Zhang, a postdoctoral research fellow in Zheng’s lab.

Zheng and her colleagues are excited to use the PLC on a variety of other electrocatalytic materials, and have already begun investigations into problems in lithium and zinc batteries. The team is optimistic that details revealed by the PLC-enabled TEM could lead to improvements in all electrochemical-driven technologies.

New insights into a popular catalyst

The scientists tested the PLC approach on a copper catalyst system that is a hot subject of research and development because it can transform atmospheric carbon dioxide molecules into valuable carbon-based chemicals such as methanol, ethanol, and acetone. However, a deeper understanding of copper-based CO2 reducing catalysts is needed to engineer systems that are durable and efficiently produce a desired carbon product rather than off-target products.

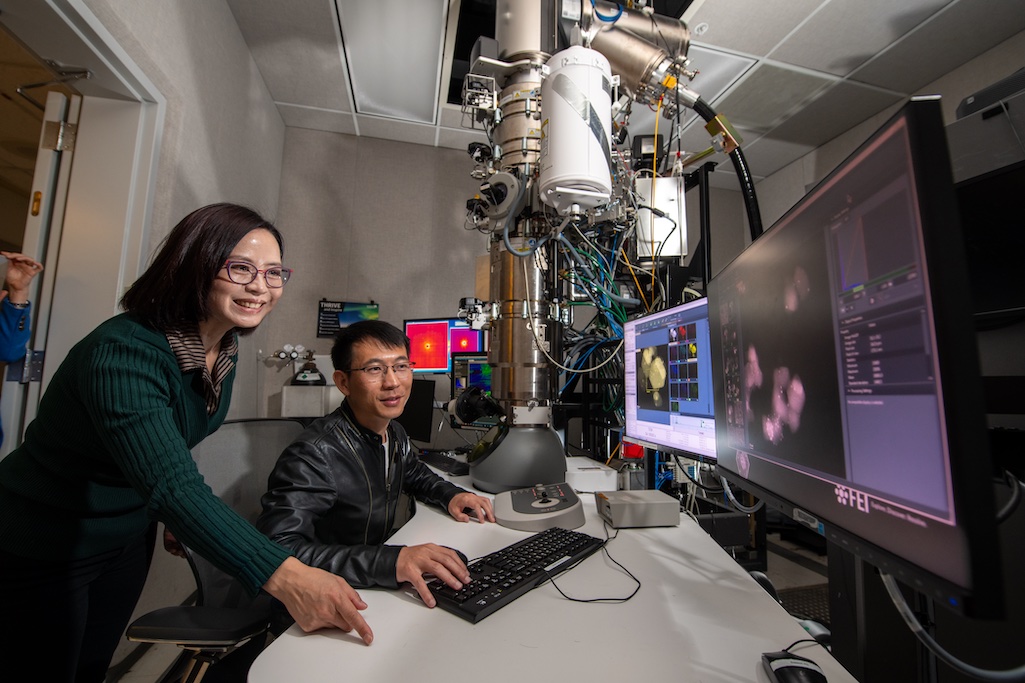

Zheng’s team used the powerful microscopes at the National Center for Electron Microscopy, part of Berkeley Lab’s Molecular Foundry, to study the area within the reaction called the solid-liquid interface, where the solid catalyst that has electrical current through it meets the liquid electrolyte. The catalyst system they put inside the cell consists of solid copper with an electrolyte of potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3) in water. The cell is composed of platinum, aluminum oxide, and a super thin, 10 nanometer polymer film.

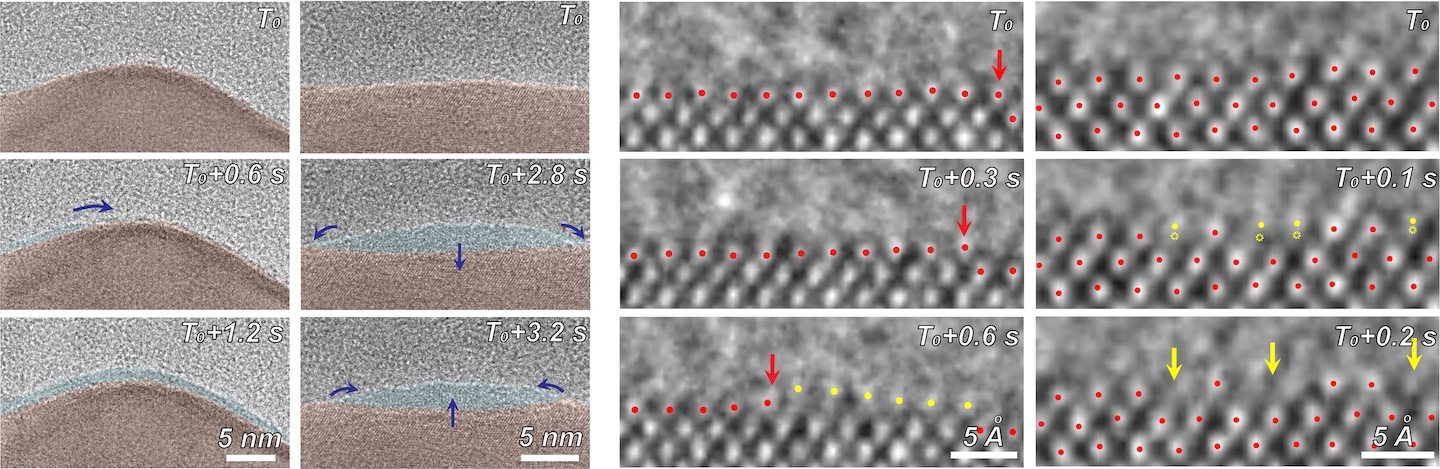

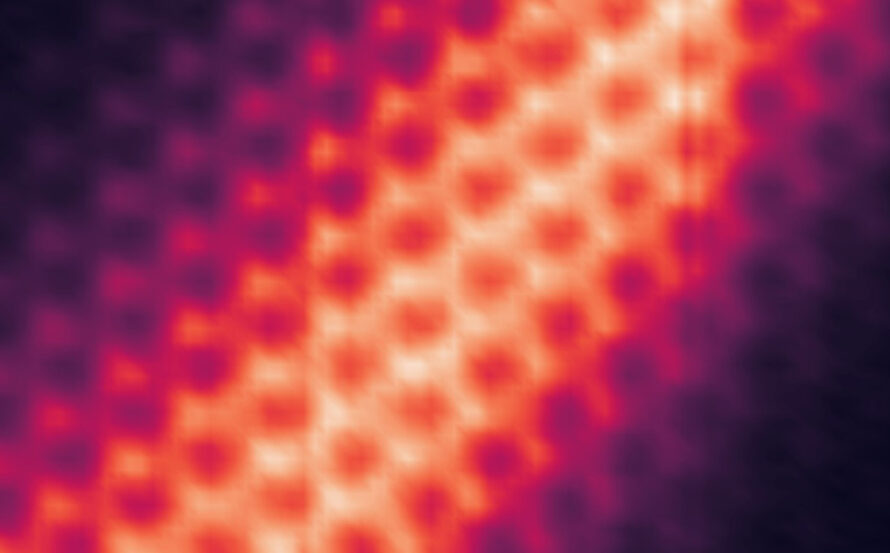

Using electron microscopy, electron energy loss spectroscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, the researchers captured unprecedented images and data that revealed unexpected transformations at the solid-liquid interface during the reaction. The team observed copper atoms leaving the solid, crystalline metal phase and mingling with carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen atoms from the electrolyte and CO2 to form a fluctuating, amorphous state between the surface and the electrolyte, which they dubbed an “amorphous interphase” because it is neither solid nor liquid. This amorphous interphase disappears again when the current stops flowing, and most of the copper atoms return to the solid lattice.

According to Zhang, the dynamics of the amorphous interphase could be leveraged in the future to make the catalyst more selective for specific carbon products. Additionally, understanding the interphase will help scientists combat degradation – which occurs on the surface of all catalysts over time – to develop systems with longer operational lifetimes.

“Previously, people relied on the initial surface structure to design the catalyst for both efficiency and stability. The discovery of the amorphous interphase challenges our previous understanding of solid-liquid interfaces, prompting a need to consider its effects when devising strategies,” said Zhang.

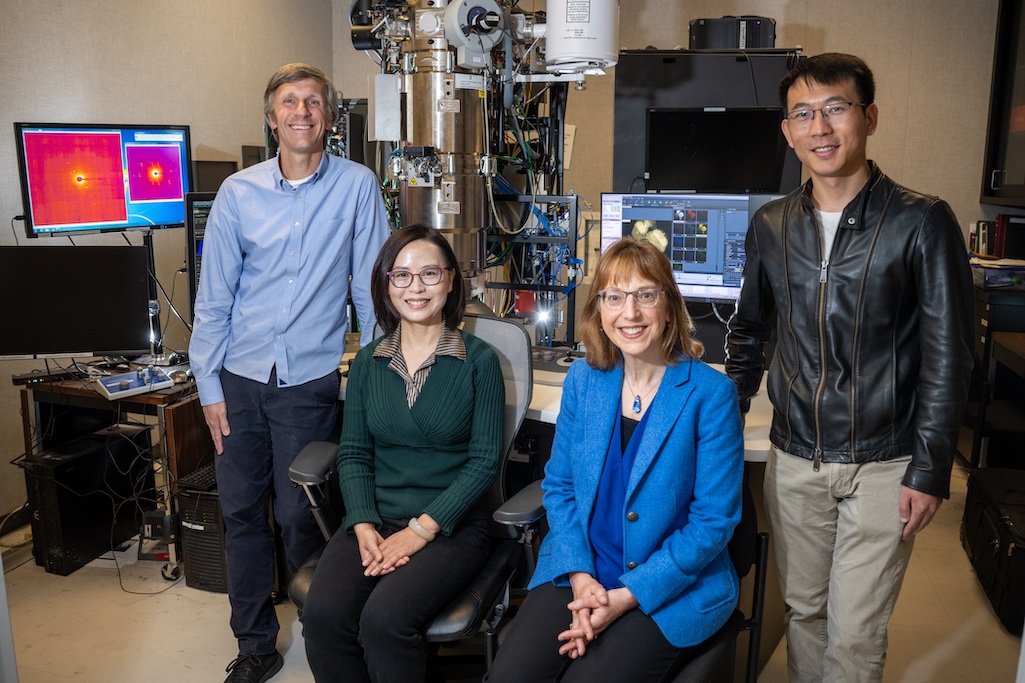

(Left to Right) Peter Ercius, staff scientist, National Center for Electron Microscopy (NCEM), Haimei Zheng, senior scientist, Materials Science Division (MSD), Karen Bustillo, scientific engineer, NCEM, and Qiubo Zhang, Postdoctoral Researcher, MSD, photographed at the ThemIS in-situ microscope at NCEM of the Molecular Foundry. (Credit: Thor Swift/Berkeley Lab)

“During the reaction, the structure of the amorphous interphase changes continuously, impacting performance. Studying the dynamics of the solid-liquid interface can aid in understanding these changes, allowing for the development of suitable strategies to enhance catalyst performance,” added Zhigang Song, co-first author and postdoctoral scholar at Harvard University.

The technology is now available for licensing by contacting [email protected]. The other authors on this work were Xianhu Sun, Yang Liu, Jiawei Wan, Sophia. B. Betzler, Qi Zheng, Junyi Shangguan, Karen. C. Bustillo, Peter Ercius, Prineha Narang, and Yu Huang. Funding was provided by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science. The Molecular Foundry is a DOE Office of Science user facility.

###

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab) is committed to delivering solutions for humankind through research in clean energy, a healthy planet, and discovery science. Founded in 1931 on the belief that the biggest problems are best addressed by teams, Berkeley Lab and its scientists have been recognized with 16 Nobel Prizes. Researchers from around the world rely on the Lab’s world-class scientific facilities for their own pioneering research. Berkeley Lab is a multiprogram national laboratory managed by the University of California for the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

DOE’s Office of Science is the single largest supporter of basic research in the physical sciences in the United States, and is working to address some of the most pressing challenges of our time. For more information, please visit energy.gov/science.

This Alloy is Kinky

New Technique Lets Scientists Create Resistance-Free Electron Channels